Equity crowdfunding market no longer the preserve of start-ups

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For enterprises seeking seed capital or money to expand, intriguing possibilities are on offer by the fast-growing UK equity crowdfunding market, which enables individual investors to buy stakes in companies online — sometimes putting in as little as £10.

Equity crowdfunding websites such as Crowdcube, Seedrs and SyndicateRoom, enable businesses to pitch to communities of backers. They offer companies an innovative route to raising capital, often from enthusiastic customers, and open new investment areas to the public.

Questions have been raised, though, about whether inflated valuations are leaving investors at risk of failing to make a return in proportion to risks and whether in some cases they have adequate protection against dangers, such as heavy dilution of their shareholdings.

The Financial Conduct Authority, which regulates the sector, has warned that crowdfunding is risky for investors, with the message: “you are very likely to lose all your money,” because most start-ups fail.

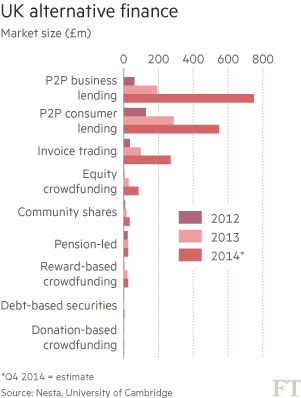

The sector, barely five years old, is small but expanding. Last year it raised £84m, up from £3.9m in 2012, according to Nesta, an innovation charity.

That was out of a total UK alternative finance market estimated at £1.74bn. The UK is ahead of the US, which is still developing rules for retail equity crowdfunding.

“Equity crowdfunding is quite capable of raising £1bn a year, maybe more,” says Stephen Hazell-Smith, who co-founded Aim and is chairman of Business Agent, a crowdfunding aggregator.

But, he adds: “People will be eagle-eyed looking for failures.”

There are more than 30 platforms. Nesta found the average amount raised was almost £200,000, with 125 investors putting in £1,599 each.

Augmentum Capital, a venture capital fund backed by Lord Rothschild and Neil Woodford, the fund manager, recently led a £10m investment round into Seedrs, while corporate brokers Numis bought 8.49 per cent of Crowdcube as part of a £6m funding round.

Equity crowdfunding is also attracting established companies. Sugru, a company that makes a mouldable putty, raised more than £3.5m via Crowdcube, the largest platform, in July. ISDX-listed Chapel Down winery, a UK wine producer, raised nearly £4m via Seedrs last year. Crowdcube plans to offer retail investors the chance to invest in London stock market floats.

“It’s about having options and being able to get the money quickly,” says Luke Lang, Crowdcube’s co-founder. “It can be quicker than protracted conversations with venture capitalists and angel investors.”

Companies see a benefit in having customers as shareholders, who can turn into “brand ambassadors” for their products and services. Investors often support businesses they identify with, whether it be craft beer, solar energy or computer games. It is less clear how well that might work for, say, a machine tool manufacturer.

Crowdfunding can help to fill the equity gap for start-ups but it is not necessarily easy. Crowdcube rejects 85 per cent of businesses that apply, for reasons such as being unable to substantiate claims in a pitch. Nearly half of pitches on the platform fail to reach their targets, meaning fundraising fails.

“They have to work at it,” says Tom Davies, chief investment officer at Seedrs, where six out of 10 fail to reach their target. “They have to do a lot of marketing around the crowdfunding campaign.”

Platforms have various models: on Crowdcube, investors hold shares in companies directly. Seedrs acts as a nominee shareholder on behalf of investors, managing the investment for them. On SyndicateRoom, a “business angel” acts as lead investor and negotiates terms before funding is opened on the same terms to the crowd.

On Crowdcube, all but the largest investors receive “Class B” shares, with no voting rights or contractual protections against dilution, such as “pre-emption rights”, whereby existing investors must be offered shares before they are made available to anyone else. Crowdcube says the 2006 Companies Act gives adequate protection from unlawful dilution.

Some companies have been criticised over valuations, notably craft brewers BrewDog and Camden Town Brewery. Valuations matter, because even if investors have diversified portfolios they need to earn good returns from the few that do well.

But Stian Westlake, executive director of research at Nesta, says: “It isn’t clear to me that there is something inherent about equity crowdfunding that is more likely to generate unrealistic valuations.”

It may take at least five years before rates of return can be properly gauged as the initial cohort of businesses is sold or floated. “It is likely that the bad news will come before the good news,” Mr Westlake says. “By then we hope there will have been some success stories, even if these are anecdotal.”

Comments