Presidential poll: Race for Brazil’s driving seat

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Marlly Maués Maciel has little doubt about how her poor riverside community is likely to vote in Brazil’s presidential election, which kicks off next Sunday.

“Here the river traditionally votes red,” says the resident of Rio Itacuruçá, a waterway in Brazil’s Amazonian state of Pará, referring to the colour of the ruling centre-left Workers’ Party, or PT, of incumbent President Dilma Rousseff.

The reason soon becomes clear. The 23-year-old, who lives in a wooden hut on stilts among açaí palms, has three daughters by three different fathers. The men chip in to help. But like many here, her income consists mostly of the R$306 ($125) she receives from Bolsa Família, a monthly stipend the government pays poor families that was introduced by the PT more than 10 years ago.

Most likely to be decided in two rounds, with a run-off scheduled for October 26, the election has turned into a dramatic contest between two women with compelling life stories. They are President Rousseff, a technocrat and former leftist guerrilla, and Marina Silva, a former senator who was raised as an illiterate rubber tapper and is casting herself as an agent of change.

Until early August the election was the PT’s to lose. More than 14m Brazilian families receive the Bolsa Família, or about one quarter of the country’s 200m population, providing the PT with what had seemed an almost unassailable political base. During the party’s 12-year rule, more than half of Brazil’s population has risen into the middle-class defined as those earning more than R$1,734 per capita per household.

Yet the PT has arguably become a victim of its own success. Brazil’s new lower middle class have become disenchanted users of public services. The country’s shoddy hospitals and dismal state schools, as well as perceived endemic corruption and concerns that a stalling economy may signal tougher times ahead, are leading many to seek change.

This has turned the 2014 election into the closest contest in a generation, with the disgruntled in Brazil rejecting the status quo by looking to Ms Silva. This has echoes of other recent elections. In India this year voters turned against the incumbent government by electing Narendra Modi, a politician from a mainstream party but who was perceived as risky in a multicultural country because of his rightwing past. And in Indonesia, voters elected a relative political outsider, Joko Widodo.

“Marina is the closest thing you have to a protest vote,” says Timothy Power, lecturer in Brazilian studies at Oxford university.

For global investors, the vote is crucial. With the economy in technical recession in the first half and its fiscal accounts deteriorating, the world’s seventh largest economy – once an emerging market star – could be headed for junk bond status unless the next president makes tough spending choices.

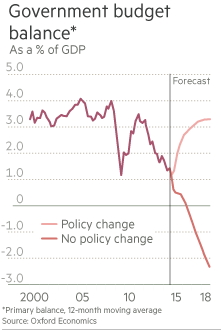

“If the next president does not signal material change in the way things are moving on the fiscal side we could see, during the first or second quarter of 2015, [a] downgrade by a credit-rating agency,” says Marcelo Salomon, economist at Barclays.

The anointed successor of her wildly popular predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Ms Rousseff was initially welcomed in 2011 by markets as a competent technocrat. But her government began to intervene in fuel and energy prices and the financial sector, undermining confidence, economists say.

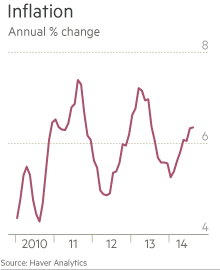

Economic growth has slowed the most since the 1990s, averaging under 2 per cent a year, while inflation is near the top of the central bank’s range of 6.5 per cent. The primary surplus, the figure before interest payments, has deteriorated, raising concern over the long-term health of public finances. Standard & Poor’s downgraded it to one notch above junk this year while Moody’s Investors Service last month changed the outlook on its credit rating to negative.

On the political front, Ms Rousseff won plaudits in her first year by firing ministers accused of corruption and by extending Brazil’s social welfare programmes. But popular dissatisfaction with public services was clear to see when millions protested against government spending on the 2014 football World Cup. Her reputation was further damaged by a corruption scandal in Petrobras, the state-owned oil company she led before becoming president.

In spite of all this, Ms Rousseff was still leading in the polls in early August against Aécio Neves, the candidate of the PT’s traditional rival, the centrist, pro-business PSDB, when tragedy intervened. Her third-placed rival, Eduardo Campos, was killed in an air crash, opening the way for his vice-presidential candidate, Marina Silva, to stand in his place.

Ms Silva performed strongly in the 2010 presidential election, winning third place with 19m votes without the backing of a mainstream party. Her campaign for 2014, however, got off to a rocky start when her would-be party, Rede, failed to attract enough signatures to register for the election. This forced her to join Mr Campos as vice-president of his Brazilian Socialist party.

Born dirt poor, Ms Silva taught herself to read and graduated in history. She overcame illness to campaign alongside Brazil’s most famous environmentalist, the late Chico Mendes, against deforestation by ranchers. After joining the PT she served as environment minister under Mr Lula da Silva but quit in 2008 after falling out with him.

“I think that a national leader with the characteristics of Marina is rare anywhere in the world,” says Eduardo Giannetti, a prominent Silva economic adviser and a professor at São Paulo’s Insper business school. “She is in the line of Nelson Mandela, or Mahatma Gandhi, or Martin Luther King, a leader who is grounded in ethics and values.”

After entering the presidential race on August 18, Ms Silva immediately took a lead in the polls over Ms Rousseff when voters were asked who they would choose in a second round run-off.

Her campaign pitch is to combine the “best elements” of the leftist PT and the centrist PSDB. She is promising to preserve the social benefits of the PT, particularly the Bolsa Família, while returning to the responsible economic management of the PSDB. When it was in power in the 1990s it introduced inflation-targeting, fiscal prudence and a floating currency that is credited with overcoming Brazil’s history of runaway prices. She is also pledging full independence for the central bank .

Ms Silva’s advisers say she would immediately make the adjustments being demanded by the markets – restoring the budget primary surplus to healthy levels, estimated by economists at about 3 per cent of gross domestic product compared with under 2 per cent now. This would create a “positive shock” in which inflation would fall and interest rates – standing at 11 per cent – could be lowered.

In the two weeks following her nomination, the market rallied nearly 9 per cent before giving up some of those gains as Ms Rousseff staged a comeback in the polls. “Her economic programme would bring a positive regime change to Brazil – 2015 will likely be a year of adjustments, but better growth could kick in during 2016,” Barclays said in a report predicting a Silva victory.

Many businessmen, while reluctant to comment publicly for fear of being seen to take sides, privately support her economic programme. They point to Ms Silva’s close association with business figures, such as Guilherme Leal, a billionaire who built one of the country’s most prominent brands, beauty product chain Natura, and Maria Alice “Neca” Setúbal, a member of one of the controlling families of Itaú-Unibanco, the largest private bank.

Some question, however, whether she will maintain a hard line on the environment, blocking much-needed infrastructure projects and inhibiting Brazil’s most competitive sector, agribusiness. Others are concerned about whether she will be able to keep her spending promises, particularly a pledge to increase expenditure on health to 10 per cent of the budget. But Mr Giannetti says balancing the budget will be the priority. There will be no “economic adventurism”, he says.

Ms Silva’s message also seems to be getting through to voters. “The Dilma government today is a mess. It’s the same old story – before she came in, she promised a lot and afterwards ended up doing nothing,” says Rosa Antonia dos Santos, a maid in São Paulo. “I think Marina could make some big changes.”

But in recent weeks Ms Rousseff, armed with an overwhelming advantage in free election television advertising, divided between candidates based on their support in Congress, has waged a slick negative campaign saying a Silva victory could cost Brazilians their hard-won improvements in living standards. In one recent advertisement, the PT drew a link between Ms Silva’s proposal for central bank independence and food disappearing off the tables of ordinary Brazilians.

The PT has also reinforced its message of how much things have improved during its rule. In spite of Brazil’s weak economy, unemployment remains low and real wages are rising. The onslaught has allowed Ms Rousseff to draw level with Ms Silva in the latest poll by research group Ibope at 41 per cent each.

A legitimate concern over a Silva government, analysts say, is how she would rule given her Socialist party is likely to only have 30-40 seats in the 513-seat lower house. The party might be able to count on another 50-60 seats from the PSDB but it would need more than 200 to control the house.

This would imply that in spite of her promises to change Brazilian politics, Ms Silva would be forced to engage in the traditional wheeling and dealing of ministries with other parties, to get her policies through. Failure to do so could lead to a lame-duck presidency. “Parties don’t support you in Congress just because they like you, they do it for seats at the cabinet table,” says Mr Power.

For Ms Silva the next few weeks will be crucial. After the first round she will have equal television time to attack Ms Rousseff. Her challenge in the coming weeks will be to convince Brazil’s lower middle class and poor to trade the relative security of the PT for the unknown in search of a better future.

“While Brazilians want change, they clearly want ‘safe’ or ‘reliable’ change that will not put the economic gains of the last decade at risk,” says Tony Volpon, an economist with Nomura .

For Brazil the stakes are equally high. Both candidates promise a radically different vision on the economy – Ms Rousseff more of the same formula that has led the country into technical recession and Ms Silva a plan to return to more orthodox policies – Brazil’s prosperity over the next four years is in the balance.

The welfare search for a nation’s lost generation

Based in Abaetetuba, a vigorous market town that serves remote river communities in Brazil’s Amazonian state of Pará, Iricina Aviz de Oliveira is responsible for conducting “busca ativas”, or active searches.

These are trips into the field to find people in extreme poverty who are not yet receiving federal government help or to assist those on social welfare but who are either having trouble meeting some of the conditions, such as sending their children to school or to have vaccinations.

Many of the families are so isolated from mainstream society that they do not even have basic documents, such as marriage or birth certificates.

“We found a boy once who did not even have a proper first name or last name, just a nickname, Tatu [Armadillo],” says Ms Oliveira. “When we registered him, at the age of 12, he finally chose a real name, Benedito [Benedict].”

“Active search” is part of an extensive system of welfare benefits built around the Bolsa Família, a monthly stipend paid to the poor on condition that they send their children to school and health clinics.

At a cost of about 0.5 per cent of gross domestic product, the stipend has been hailed as a success, contributing to a decline in poverty from more than 16 per cent of the population in 2007 to 9 per cent in 2012, says the World Bank.

Comments