Heidegger’s hut and Wittgenstein House

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Two of the greatest thinkers of the 20th century, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, were born in the same year – 1889. Heidegger, at least in his writing, seemed the more concerned of the two with architecture. “We attain to dwelling,” he wrote, “only by means of building.” The house, for Heidegger, was an expression of an existential act, of “being in the world” and, when he wrote these words in the 1920s, the house he was thinking of was almost certainly the one he was in – a small wooden cabin in Todtnauberg, in the Black Forest, which he called “The Hut”.

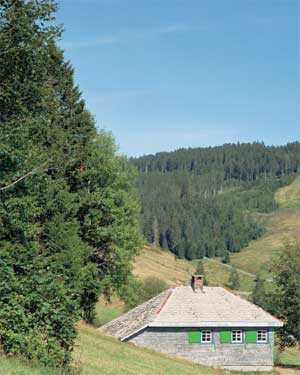

This wasn’t a building Heidegger had designed. It was a typical, modest mountain cabin. Set into a green hillside, the hut had small, square windows, timber walls and a shingled pitched roof. It appeared very much how a young child might draw a first approximation of a house. The interior was sparse: boarded walls, a few bookshelves and a couple of cast-iron wood-burning stoves. This was a functional house for farmers, whose interest in the land was more practical than picturesque, and whose everyday lives were simple and ascetic compared to the luxurious comforts of bourgeois Marburg and Freiburg, where Heidegger taught. The timber hut proved the perfect setting to crystallise Heidegger’s thinking into the elemental connections between earth and sky, between dwelling, building and being.

Heidegger’s reputation (although not his influence) suffered greatly from his association with the Nazis who, when they were thinking of the ideal dwelling, were probably thinking of something similar to this vernacular Black Forest hut. It represented an idea of Aryan purity, straight from the soil and imbued with an honest German domesticity.

Wittgenstein also had a thing about huts. He did some of his greatest work in a timber cabin in Norway and, later, in a simple house in rural Ireland. But the house I’d like to look at was built and designed by Wittgenstein – who had no architectural training – not for himself but for his sister.

Before becoming a don at Cambridge, Wittgenstein had studied engineering in Berlin and at Manchester University and, when his sister Margarethe (who was painted by Gustav Klimt) decided to commission a house, he got involved – and then took over completely.

It helps to understand the nature of the commission to know that Wittgenstein came from one of Europe’s richest families but was completely uninterested in money, giving away his inheritance to his siblings and an assortment of artists, poets and editors.

One of the recipients of his largesse had been a controversial Viennese architect, Adolf Loos. Loos’s buildings – spare, stripped, severe on the outside but often surprisingly rich on the inside – intrigued Wittgenstein and he determined to make a house using some of Loos’s ideas. If anything, the house Wittgenstein built on Vienna’s then rather unfashionable Kundmanngasse out-Loosed Loos.

The Wittgensteins had grown up in a palatial house, its forecourt adorned with a fountain and sculptures by Rodin. Brahms, Strauss and Mahler had been regular visitors, often listening to their own works performed in the huge music room. But the house Wittgenstein designed for his sister was to be something very different.

He collaborated with a young Viennese architect, Paul Engelmann, who had been a pupil of Loos and became a friend of Wittgenstein, but, according to contemporary reports, Wittgenstein soon took over. He took to calling himself an architect, even putting the job title on his letterhead.

The house, begun in 1926, was stark and stripped back to its bare bones. But it was also beautiful. Wittgenstein paid fanatical attention to the proportions of the rooms and the windows and, despite its severe façade, the composition exudes a kind of purity, an ascetic rigour very reminiscent of the designer himself.

Wittgenstein applied his engineering skill to even the smallest details so that everything worked beautifully and every fitting was self-evidently part of the house. The openings are simply punched into a white membrane façade. Mouldings are absent, columns are crowned, not with a capital, but with a negative, a recessed, reduced girth. Walls stop cleanly at ceiling and floor in the kind of perfect junctions that skirtings and cornices would normally have concealed. With every surface exposed and every joint foregrounded, there was no margin for error in construction. In one story, a metalworker queried whether one millimetre here or there would really make such a difference. “Yes!” the philosopher roared before the man had finished his sentence.

Most striking are the doors: highly engineered metal and glass constructions which, in the absence of decoration, mouldings or any kind of rich surface, become the guiding element of the interior. It is the views through the house which make it so striking, which seduce you into moving through it and which slowly reveal the complexity of the plan. The story is that Wittgenstein spent a year designing the door and window handles and another year on the radiators (which, unusually, fold around the corners). While apocryphal, these stories are not necessarily untrue.

The door furniture is, arguably, the most influential in modern times. Simple bent brass tubes are used as handles, but are fitted directly into the steel doors, with no covers or faceplates, just as keyholes are cut directly into metal doors. There is no room for movement or for shoddy workmanship. The windows feature slender steel mullions, which emphasise the height of the rooms while the reductive nature of all the fittings means that the eye is absorbed in the space and light, not the detail.

The most famous story about the house is that Wittgenstein was unhappy with the proportions and had the ceilings of a room taken out and raised by 30mm. This may conform to a particular idea of what happens when a logician builds a house, but, when that house is refined down to the barest of spaces, proportion is one of the few tools left to work with.

Like Heidegger, Wittgenstein found it easiest to write in the simple surrounds of an isolated country cabin. He returned to Cambridge after completing the house (his letterhead still described him as an architect when he returned to Britain), but his writing got done in that log cabin by a fiord in Norway. The vernacular timber cabin represents a kind of perfection of the type that the early modernists were trying to achieve, in which every element is necessary and nothing can be taken away except to make it poorer. Walter Gropius’s first house from his Bauhaus studio was a striking log cabin (the beautiful Sommerfeld House in Berlin, 1921) and the only house that Le Corbusier ever built for himself was a tiny timber cabanon, a cabin on the coast near Menton (1951).

Adolf Loos, who so influenced Wittgenstein, wrote that the farmer could create a beautiful house where an architect could not. “The architect, like almost every urban dweller, has no culture. He lacks the certainty of the farmer, who possesses culture. The urban dweller is an uprooted person. By culture I mean that balance of man’s inner and outer being which alone guarantees rational thought and action.” And that very particular idea of culture is why both Heidegger and Wittgenstein felt most comfortable in a hut, untouched by architects, in the middle of nowhere.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture critic

Comments