Triple A quality fades as companies embrace debt

Simply sign up to the Capital markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

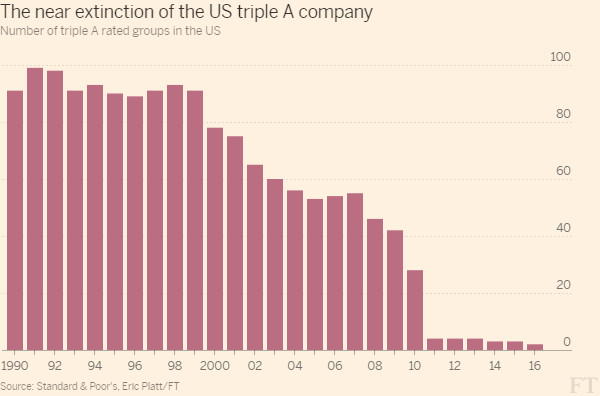

The triple A rated company is nearly extinct. Just a handful of companies in the world retain the coveted rating from Standard & Poor’s after ExxonMobil was downgraded last month.

In the US, the number has fallen to two — Johnson & Johnson and Microsoft. In 1992, there were 98 US companies that held the highest credit rating from S&P.

The demise of triple A-rated companies reflects a dramatic rise in the use of debt to help bolster shareholder returns and fund takeover activity.

This trend shows little sign of ending in the current era of ultra-low borrowing costs.

For example, investment grade and junk-rated companies have added nearly $4tn of debt to their balance sheets since the start of 2008, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch, roughly the size of the market for US state and city bonds.

“One thing is clear: the trend away from financial conservatism that began in the early 1980s continues to this day,” says Thomas Watters, an analyst with S&P.

Management teams have long relied on debt to increase the value of their companies, spurring a steady decline in rating quality.

The benefit when a company with no debt begins to add leverage, is often a higher market valuation. But too much corporate paper, at companies such as Sears, TXU and debt-burdened radio operator iHeartMedia, can stifle business and ultimately lead to failure.

Groups holding the top credit rating in the US, which includes offerings from Harvard, MIT and Stanford, yield roughly 2.6 per cent, according to Barclays. Double A-rated companies by contrast have a slightly lower average yield of 2.3 per cent.

Bond yields fall when prices rise.

Part of the divergence is the lack of triple A-rated debt and the weight Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson exert on the indices.

There is roughly $62bn of triple A-rated corporate debt outstanding — more than four-fifths of which is from the two companies — dwarfed by the $419bn of double A debt and $1.78tn of single A paper in the US.

“In a way, double A has become the new triple A, when you have a lot less triple A debt out there,” says Nick Gartside, chief investment officer of international fixed income at JPMorgan.

Exxon sold $12bn of debt earlier this year after investors had been notified that the company was on review for a downgrade, with 10-year yields near 3 per cent.

Jeremy Siegel, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, says the most recent financial crisis highlights the speed at which companies — even high-quality ones — could lose access to capital markets.

At its depths in September 2008, corporate lending evaporated as banks retrenched, leaving groups with immediate financing needs on the ledge.

“It is the result of the financial crisis,’’ he says. “The severity of this shock is now being factored into a lot of these [rating] models. Credit may not be available at any price in a crisis and that’s something to consider.”

Prof Siegel adds: “Companies, unless they are unbelievably cash-rich, are just not being given triple A ratings. We won’t get back to the number of issues we had in the 1960s that might have had a triple A rating. Those are perhaps gone forever alongside the rise of global competition.”

Investors and strategists say they do not anticipate companies will rapidly cut their leverage, limiting a broad improvement in rating quality.

So far, triple A companies that have increased leverage have not had to pay tremendously more to borrow.

While investors are seeing defaults from energy and mining groups as a result of the shakeout across the commodity market, led by oil prices sliding from their peak of 2014, they say the risk of default at the upper tiers of the rating spectrum remains de minimis.

Corporate debt rated triple A suffered a loss of 0.02 cents on average because of default over a five-year period, says Jeffrey Rosenberg, chief fixed income strategist at BlackRock. In comparison, double A bonds lost 0.2 cents on average over the same period.

“The difference is not a very large amount in absolute sense, in terms of the value,” Mr Rosenberg adds. “What benefits do the issuer get for a triple A rating versus a double A and what benefits do they give up?”

Comments