Entrepreneurs are only taught half the lesson

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Entrepreneurial education today is incomplete.

It is no wonder that so little of the new knowledge produced from institutions of higher learning is commercialised; there is no formal methodology for teaching students how to transform their business acumen into value-creating enterprises.

We are only building half of the bridge to entrepreneurial utopia and we need to finish the job. Some entrepreneurs work it out for themselves and cross the shark-infested waters to entrepreneurial success, but too few. And if we look beyond the headline-grabbing start-ups, innovation within existing companies is not exactly going well either. Such innovations, either within large corporations or in start-ups, are the work of entrepreneurs and are what create wealth and employment.

Becoming an entrepreneur requires a blend of knowledge – knowledge that is typically taught in different departments at universities. In business schools, however, the entrepreneurship curriculum has generally managed this paradox by teaching entrepreneurship as a capstone course; building on core courses in the specific disciplines of strategy, marketing, finance, operations and management.

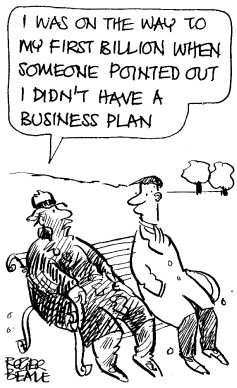

The creation of a business plan is a quintessential business education activity and is typically the initial entrepreneurial course taught in business schools. Additional courses in entrepreneurship often build on this course, covering topics such as business resourcing and managing the growth of nascent businesses. But as good and as necessary as these courses are for successful future entrepreneurs, they are simply not sufficient.

Where do these ventures that business schools put into operation via a business plan come from in the first place? Bolts of lightning? Divine inspiration? Sometimes.

However, divine inspiration is not the foundation for an innovation economy. We need to teach students how to use their abilities to build different businesses; show them how to build on their knowledge using the subjects they came to university or business school to study.

Business is the vehicle that creates and captures value from an individual’s unique abilities. But any discussion about how these abilities should be leveraged to create a business should not start with the business but with the individual and his or her capabilities. It is this discussion that is missing from the entrepreneurial education curriculum.

Before a business is given the operational go-ahead through a business plan, it should be assessed to see if it is worth building and what “it” is should be clearly articulated. Product developers design their goods before going on to build and test them; so too should business builders. What is the business designed to do and why? The opportunity that the business is addressing also needs to be identified.

It is these pre-business planning skills – business design, business assess-ment and opportunity identification – that in general are missing from the entrepreneurship curriculum.

There are two reasons for this: first, successful serial entrepreneurs carry out these activities as a matter of course, almost instinctively. People do not write or talk about things that they do unconsciously.

Second, these activities are below the water line – actions that are carried out before a new venture becomes visible. It is far more interesting to talk to an athlete about her performance in the event than the training that enabled that performance.

Such foundation skills, while not in themselves glamorous, enable the creation of glamorous new ventures. For, as the sinking of the Titanic demonstrates, what is below the water line and often not visible is capable of destroying dreams. Let us not sink our dreams of an innovation economy by providing half an entrepreneurial education.

It is time to complete the entrepreneurship curriculum. Business schools are well positioned to lead that charge. Now is the time for them to step up and do just that.

The author is managing director of the University of Michigan’s Zell Lurie Institute at the Ross School of Business.

Comments