The Diary: Philip Pullman

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At last I have discovered what social rank I am. Not that I ever wondered very hard about that, but still. I am a yeoman. We recently bought seven acres of rough land right next to our house. It hadn’t been looked after for 25 years or more, and it was full of chest-high thistles and nettles and hogweed, and the ground was ankle-twistingly covered in hummocks and tussocks and anthills and molehills and rabbit holes.

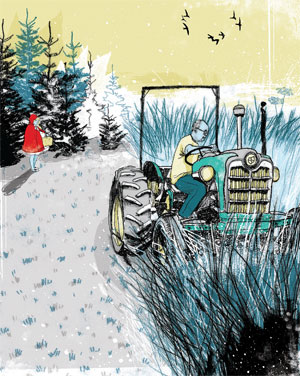

Naturally, I had to have a tractor, and very fine I feel sitting on it, bumping and lurching over the ground as I slice off the weeds with a topper, which is what an agricultural mower is called, apparently, because it takes the top off. The ground looks much better when I’ve finished but I’ve discovered that you never do finish, because the wretched weeds grow up again at once. We’d like the place to turn into a wildflower meadow with a grove of noble trees somewhere in the middle but the trees will take 200 years to grow and the wildflowers don’t just look after themselves. There’ll be plenty of topping to do yet.

And as it’s only seven acres I can’t call myself a gentleman, but I do own it, so I’m not a villein. Yeoman it is.

…

Whenever I go into Oxford (I live about five miles outside) I like to visit the Covered Market, sometimes to buy some cheese from the immense range on offer at the Oxford Cheese Company, sometimes to buy a quarter of a pound of lapsang souchong from Cardews, the tea and coffee shop, and sometimes just to look around.

The Covered Market has been there for more than 200 years, but it’s in danger. A shop called Chocology, for example, has just had to close. The owner says that when he opened the shop in 2001 the city council, which owns the market, charged him £13,000 in rent. Recently it told him it wanted to put the rent up to £45,000. Other shops have gone: Palm’s, a great delicatessen which I remember from my undergraduate days, has closed; there was a small haberdasher with rolls of every kind of cloth on high shelves; there was a marvellous record shop that specialised in jazz. All vanished.

There should be a place for shops like that in any civilised market place. The city council ought to remember what it’s there for: not to wring every possible penny out of hard-pressed traders but to keep this treasure of a market alive and distinct and interesting, as it should be. If it carries on like this, the place will be full of nothing but branches of Starbucks.

…

One of the great delights of summer is watching the swallows that live in our open-sided barn. They have a nest high up in the rafters, and we can tell when they’ve laid their first brood by the neat heap of guano that appears on the floor below as they pause to shove another fly into one of the little yellow beaks that gape over the edge of the nest. Into the barn, shove, swoop out again, in less than a second. And they do it all day long. When the young ones are old enough to fly, they flutter from one rafter to the next and then sit there looking as if they own the place, which in a sense they do.

A little later another heap of guano begins to grow on the floor, marking the appearance of the second brood. They all, parents and offspring alike, are now whizzing about the sky conversing in loud chirrups and twitters. Soon they’ll all gather on the telephone lines, and then they’ll be gone.

One year I found a dead swallow hanging in mid-air at the dark end of the barn. It had caught itself in a thread hanging from a shelf above. The thread was so thin that I couldn’t see it, and neither could the swallow. But it gave me a chance to hold its body in my hand and marvel at its lightness, and at the exquisite colouring of its chest and throat. This year one of the fledglings fell out of the nest. Having cleaned off the guano, my grandchildren buried it with due solemnity.

…

Recently someone reminded me of Albert Einstein’s remark about fairy tales. “If you want your children to be intelligent,” he said, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

What could he have meant by that? My guess is that he was referring to analogy. A story such as “Little Red Riding Hood” – at least in the Grimms’ version – doesn’t beat you over the head with the similarity between wolves and plausible strangers; it lets young readers (or listeners) take in the story and enjoy the thrill of the danger and the relief of the rescue, and lets them make the connection themselves. Other stories work in the same way, if we let them do it themselves and don’t insist on interpreting them.

This training in the use of analogy, of finding a likeness in unlike things, is valuable in all kinds of thinking, not least the scientific. Apparently Einstein also said: “Growth comes through analogy, through seeing how things connect, rather than only seeing how they might be different.”

At least, the internet says he did, but it sounds right to me.

…

Recently I had a conversation – took part in a conversation – conducted a conversation (I can’t find the right verb) on the stage of the Oxford Playhouse with the writer Neil Gaiman, who was nearing the end of a long tour to publicise his latest book, The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

I’d hoped to say something about my latest book too but somehow I couldn’t bring the conversation around to it. Well, next time I shall know what to do. Gaiman is an immensely versatile writer – comics, film and television scripts, novels, short stories, children’s books – and he has a strong and easy stage presence.

He was dressed all in black, which was wise. I once saw the late Iain Banks speaking on a similar occasion, and he wore a shirt the same colour as his face. The lighting wasn’t very good, and it was hard to tell where the shirt ended and he began. Since then, whenever I’ve had to go on stage, I have always worn something a markedly different colour from myself. At the Playhouse, my shirt was electric blue. Not much chance of confusion there, I think.

And I almost didn’t even manage to bring this piece around to my latest book. It’s called Grimm Tales, and it’s published by Penguin Classics, and it’s just out in paperback, and it’s worth every penny.

Comments