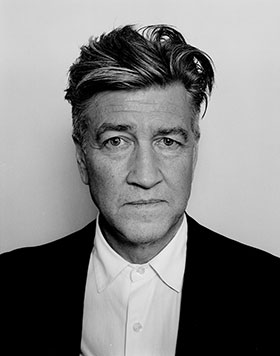

David Lynch and the factory archive

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Anyone familiar with the world of David Lynch’s first feature film, Eraserhead, will probably not be surprised by his series of factory photographs, which luxuriate in the chiaroscuro effects of light filtered through the grimy windows of abandoned industrial buildings and create a mysterious world of their own. Eraserhead is a surrealist horror movie whose main character, Henry Spencer, his hair styled as if by an electric shock, tries to care for a grotesquely deformed baby inside a claustrophobic apartment building set in a landscape very like the ones in the photographs. But to assume that they must have inspired, or been part of the research for that film would be a mistake. Lynch began to photograph factories only after Eraserhead (1977) and his next film, The Elephant Man (1980), were completed.

“Oh, way after,” he said, speaking on the phone from Los Angeles in that affectless drawl that is sometimes compared to Jimmy Stewart’s. “The films came first.”

“Maybe it was an imagined factory world,” he conceded when I pointed out the similarities to Eraserhead. But it was a world that already existed inside his head.

“I don’t know when the first factory was I photographed, but I think sometime in the 1980s. I’ve just been real lucky to be able to go to a lot of them – some working factories, but a lot of abandoned factories.”

So where did it come from, this passion for broken-down industrial buildings, for chimneys and stairwells and empty machine halls, with their rusting levers and pulleys and dials; for dark, desolate spaces that disappear into blackness?

“Well, I was born in Montana,” he began, as if in contradiction, “and I lived mostly in the northwest but my mother is from Brooklyn, New York, so we would visit my grandparents there and that city had a big effect on me. I saw different types of machines and dials and things that I hadn’t seen before, and I saw many smokestacks with smoke coming out and some with fire coming out, and I got a feeling of industry even though, maybe, I didn’t know what it was. It was so different and it held a power and when I was very little, it held a fear. Subways really held a lot of fear – subways and the tunnels going down into some place and the smell of it and the sound of it and the power of the trains, for me, when I was little.”

Lynch’s father was a research scientist for the US Department of Agriculture and the family moved frequently during his childhood. When he was five, in 1951, they were living in Spokane, Washington (the area where, 40 years later, Twin Peaks would be set and a part of the northwest known as the “Inland Empire”, the title Lynch gave to his most recent feature film, released in 2006). He went to high school in Virginia (“there’s no industry there”) and, after a year at art school in Boston and an abortive trip to Europe, in 1966 he enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia to study painting. While there, living in a house in a rundown neighbourhood with his wife and baby daughter – “the city was full of fear,” he has said – he began to make short films, one of which won him a place at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, where he moved in 1971.

“I made Eraserhead in Los Angeles,” he said, “but it was based on the feelings of Philadelphia. I got kind of resurgence . . . a thrill from Philadelphia and the architecture and a mood there. I didn’t really photograph any factories [then] but I took in a love of factories . . . factory neighbourhoods, factory workers, the sound of it all, in my mind. I always say Philadelphia is my greatest influence.”

…

So his photography grew out of film-making. “It had nothing to do with research. Most of the factories were just because I wanted to experience them and photograph them. Except in one case. When I went to northern England I was looking for places for a film called Ronnie Rocket, a script I’d written.”

This was in the mid-1980s. “Well, here’s what I’d heard for a long time: ‘If you want to see real smoke and fire and industry’ – of the kind I had in my mind – ‘you need to go to northern England.’ And so I went to northern England with my good friend Freddie Francis [the British cinematographer who had worked with Lynch on The Elephant Man]. It was one of the most depressing trips, because at that very moment in time they were tearing down a smokestack every week and putting up these ridiculous little prefab factories in their place, and so it was like, you know, it was going fast.”

Since then he has photographed factories sporadically, depending on his schedule and his location. Later this month an exhibition opens at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, based on a book edited from over three decades of factory photographs. It includes pictures taken in Berlin, New York City, New Jersey, Los Angeles and, most notably, Lódź, in Poland.

“Sometimes it was a definite planned trip to photograph factories,” he explained. “And sometimes it was an offshoot. I’d be in a place, I’d hear about something and I’d try to go there. But really, I think my friends in Poland who ran the Camerimage film festival, they’re the people who organised the most . . . different factories, and there were some beauties.”

Camerimage is the international festival for cinematographers that was founded in Poland in 1993. It began in the city of Toruń but in 2000 moved to the larger city of Lódź, home of the famous National Film School where Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polanski studied.

In that same year, Lynch received the festival award for the Director with Special Visual Sensitivity. He was also given access to some of Lódź’s many abandoned factories, the legacy of its importance as a textile centre in the 19th century.

He came away from that trip with a huge number of black-and-white factory photographs, which form the core of his collection.

“I’d heard of east Germany and Poland being the home of some beautiful factories.They [the festival organisers] said yes, they could help me get into them, and that was the deal. I went there many times and most of the times I’ve photographed factories, and then nude women at night.”

This, it turns out – not a total surprise, given his taste for good-looking actresses in his films – is his other photographic obsession. It wasn’t quite clear whether these were models, or prostitutes, or . . .

“No, no they’re not prostitutes,” he said. “They’re girls who don’t have a problem being photographed and they’re very good girls. I think you could say that throughout time, the female figure has been pretty extraordinarily loved but it’s an inexhaustible realm, and the way the light plays, it’s just a continual thrill, it’s unbelievable.

“[It’s] the same with the factories, the light that plays inside these buildings, it’s really a spiritual experience.

“It’s not an intellectual thing. It’s just, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so a beautiful garden for some would give the same thrill – but there’s something about a factory that’s like a beautiful garden.”

Does he always photograph the factories in black and white?

“Yes. I don’t like colour. I’ve taken colour photographs in factories and sometimes they’re kind of thrilling. But the real factories that I love, they’re black-and-white experiences. Colour putrefies them.

“And I like ’em in the winter. I don’t like green leaves. I really love the oil-impregnated earth, you know, where the earth is gleaming with black oil and there is steel and brick and glass and these machines, and smokestacks and the smoke and the fire. It’s an amazing, phenomenal thing.”

I wondered whether he had any interest in the history of what he photographed.

“Zero. Pretty much zero,” he replied. “These were mostly textile factories and they were electrical factories. People tell me stories sometimes. But honestly it’s not what drives me, not one bit.”

So what is it that he gets from them?

“You know, I always say I like organic phenomena, and the factories that I love are from a certain era and nature is always reclaiming them, and on the walls you see a man-made thing – but nature is playing a big role in the thing as well. Like the light pouring in is nature and the black trees around them is nature, the walls are being reclaimed by nature . . . Something is happening to the machines. It’s not rust . . . it’s maybe a little bit of dust and some age . . . from the machines being old. It’s just all these little parts catch the light in a certain way, it’s such a thrill. Beyond the beyond.

“Such shapes and textures and there’s a deep mystery . . . there are a lot of parts of the factories that are much darker and I always say whenever there is darkness, the mind kicks in and creates your stories and mysteries, and it’s all in there, a beautiful world.”

…

Although much of the strangeness of his early black-and-white films comes from the way they were intricately lit, his photographs use only natural light – except, he says, for a couple of times where some flashlights were used, when there was no light whatsoever.

“Yes, and sometimes that [the blackness] is really importantly beautiful and other times you wish you had a little bit more light. But you know, you can do long exposures, you can do different things but it’s all the light that comes in and nothing added.”

I wondered if he ever filmed in the factories.

“No, no no. If there was a scene that took place in there, then you’d film it. But there’s 10,000 different stills that are so incredibly beautiful.”

In the past few years, Lynch has been one of the great advocates of digital technology. But for the factory pictures, he stuck to the old processes.

“Well, I was touting digital up one side and down the other. It’s a great medium. But for these factories, it’s black-and-white film. It gets something that digital doesn’t get. What the emulsion gets is . . . I mean, they’re trying to get it in digital and they’re making great progress.

“But there is something about the organic process that’s really magical. That’s why a lot of these purists are going back to vinyl records and workin’ with analogue in the studios, and they’re shooting film – celluloid not digital.”

Lynch is well known for spending the periods between film productions on some of his other favourite pastimes, which include painting and drawing, composing music, transcendental meditation (he’s been practising since the 1970s and started the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace in 2005), drinking coffee (he has his own brand) and making short films for the internet such as Rabbits and the series Dumbland, which was originally available only to members who signed up to his website. In 2011 he opened a nightclub in Paris called Silencio (named after the club in Mulholland Drive), and most recently he has been working on what he describes as “built” photographs, constructed from different visual elements which he puts together using Photoshop. These will be exhibited in Paris at a show that opens this week.

“Just experiments” is how he described them. “I call it [the show] Small Stories. They have little stories – not that I’ve written – you make your own. If something’s untitled, you still end up making something. You can almost hardly stop it from happening.”

In 2010, Camerimage moved again, this time to the city of Bydgoszcz. In 2012, Lynch was given a Lifetime Achievement Award and, as something of a festival superstar by now, the keys to the city. Despite his avowed lack of interest in the factories’ history, he recounted his latest discovery with some enthusiasm.

“The last time I went to Poland, I went to Bydgoszcz. They don’t have the same kind of factories there but they had an incredible thing – a munitions factory where munitions for the second world war on the German side were manufactured. And not in just one building, but in many, many, many buildings in the woods. And every building had, on the roof, trees growing, so helicopters and airplanes couldn’t see them. They were camouflaged. And they were also separate, so that if something went wrong and a building blew up, it wouldn’t affect the other buildings. And one wall of every building was weaker than the other walls, so that wall could blow out and it would save the rest of the building. A lot of thought went into these places. And now they’re completely empty.”

Any machinery, he said, had been taken away by “the Russkies”. But “in their emptiness, it’s like someone set up an installation that was so beautiful, and I gotta photograph that place.”

David Lynch’s ‘The Factory Photographs’ is at The Photographers’ Gallery from January 17 to March 30; www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk. The associated book is published by Prestel, £40; www.prestel.com. ‘Small Stories’ will run at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, from January 15 to March 16; www.mep-fr.org

Comments