Corporate Japan struggles to promote women workers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For those hoping to empower Japan’s women and unleash the economic might of the country’s “silent asset”, the term kensetsu komachi offers hope. It literally means “construction — young women” and relates to a generation of females working in Japan’s chauvinistic building industry.

Many people worry that further progress on gender diversity will be little more than cosmetic, as Japanese society is still run by conservatives — of both genders. Corporate Japan does not yet believe in the importance of diversity, says Keiko Tashiro, who chairs Daiwa Capital Markets America and is a board member of Daiwa Securities. While women may occupy senior roles, their jobs are often in parts of companies considered safe for women, such as public relations and human resources, keeping them away from the profitmaking, managerial side of business.

The last time Japan attempted serious reform was in 1986, when a new Equal Employment Opportunity Law required recruiters to avoid discrimination against women. They complied, if only on a numerical basis: recruits for large companies were streamed into two “tracks” — one clerical, the other managerial. Very few managerial places went to women and almost none of the clerical ones were staffed by men. Optimism faded as women realised their career development was not a priority for employers. That generation of women, now in their mid-50s, would ideally be entering senior management today, but not enough of them are available.

“It is only natural that women are hesitant about a promotion or a raise, because they are not trained to be ready for it,” says Ms Tashiro. Corporate Japan must show it is serious about the issue, she adds, via “affirmative action and intensive training”.

Change, furthermore, is essential if Japan is to cope with a shrinking workforce and ageing population — and it is in the building industry where some of the more positive signs can by seen. By taking up construction jobs in numbers large enough to generate new vocabulary, women are demonstrating that a demographically stretched Japan needs them immediately — even in roles previously considered unsuitable.

Miyuki Kashima, a senior executive at BNY Mellon in Tokyo, says the kensetsu komachi phenomenon is proof of change. This is despite recent surveys by the Japan Institute for Labour and Training that found only 16.1 per cent of female executives at larger companies wanted promotion, compared with 65.7 per cent of men.

“When I first saw those surveys I guessed that women didn’t want to admit that they wanted to be promoted, because they didn’t want to set themselves up to fail,” says Ms Kashima. “The results will change dramatically when women come to see that the game is fair for all,” she adds. “Time will prove that the surveys were carried out in an environment that has since changed into one of acute labour shortage.”

While some see the kensetsu komachi as limited grounds for optimism, more pessimistic observers argue that Japanese companies, reluctant to embrace the cultural changes sought by the government’s so-called womenomics programme, use a variety of tricks to give the appearance of female advancement.

Naoko Ishihara, editor-in-chief of Works magazine and an expert on women in the workforce, identifies problems with efforts to place women in senior roles. It has been difficult for women to establish long careers at Japanese companies if they go on maternity leave. Now that companies are under government pressure to fill directorship roles with women, they do not have sufficiently deep pools from which to draw.

Hence, says Ms Ishihara, “companies are rushing to appoint women directors” by hiring experts from outside their own ranks and Japan generally. Therefore, “you cannot say confidently that progress has been made in women empowerment in the workplace.” Bias is a further problem, she adds. The likelihood that those women who are promoted to senior roles will be working in areas such as PR, HR and corporate social responsibility means they will not be on the route to the very top.

Japanese culture is the main obstacle, argues Aiko Okawara, a successful entrepreneur and co-founder of the Japan chapter of the Women Corporate Directors group. Japanese women tend towards non profit-generating divisions of their companies because male-dominated areas such as sales involve lifestyles that are not compatible with motherhood in a society where domestic help is rare and women are expected to bear the brunt of child-rearing.

Although Japanese women such as Ms Okawara have proved to be skilful investors and business people, society has not been keen to let them loose in the wide world of entrepreneurship. The possibility of that changing, with women gaining access to more borrowing, for example, represents one of the brighter hopes of womenomics.

“Japanese women would be risk takers if given the chance but the government never supported women or entrepreneurs,” says Ms Okawara. “We have not been able to borrow as much as men and it is only now that there are more low interest loans available.”

“The outside world may think progress is very slow but Abe has moved us forward and there is no way back.”

Womenomics explained

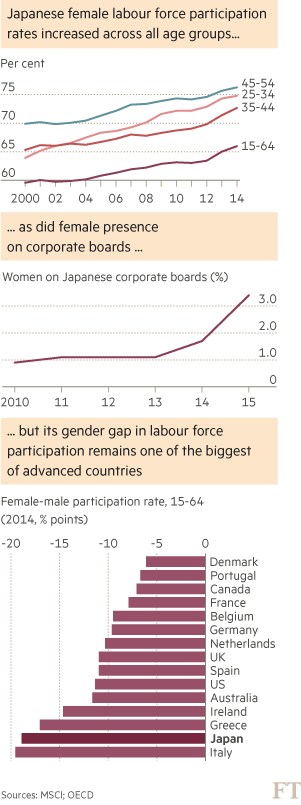

Shinzo Abe’s “womenomics” campaign has promised to raise the female employment rate from 68 per cent to 73 per cent by 2020. It also aims to encourage rapid promotion of women into management roles so that they occupy about a third of what Mr Abe broadly labels “leading positions” by the decade’s end.

The prime minister has established legislation obliging large companies to publish targets for future ratios of female managers. Even the campaign’s supporters, however, agree that reshaping corporate Japan will take time. Sexism, they say, is adaptable to changing circumstances — especially when its roots are so entwined around the national culture. December saw a lowering of campaign targets, supposedly to reflect a more realistic aim. Big companies are now required to appoint women to 15 per cent of senior positions by 2020, compared with 9.2 per cent today.

The Abe administration believes that its continuing appeal to elderly voters lies in not undermining rigid views on gender roles.

Many Japanese, for example, disparage new mothers who return quickly to work. Such views are in turn blamed for Japan’s failure to provide more supportive childcare.

Comments