Calligraphy 2.0

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

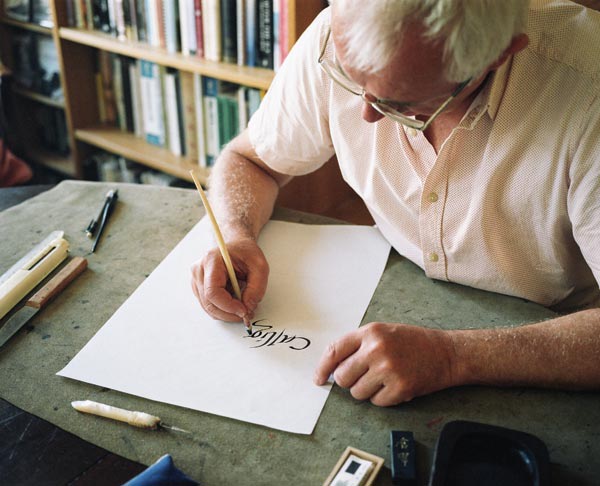

There were times in the four years that Ewan Clayton worked on his history of writing that the project threatened to overwhelm him. His flat in Brighton was overtaken, physically, by the ideas that he wanted to convey: the Post-it notes marching down the mirror; the handwritten arguments arranged on the floor; the felt-tips, pencils and laptop; his own calligraphy materials, the quill knife and 18th-century sharpening stone. “Nobody will be able to understand what the hell is going on inside my head at the moment,” he thought. Even now, with the book done, the story feels unfinished. “It’s like this vast engine inside of me.”

Clayton has lived a life surrounded by the act of writing. Like many schoolchildren, he experienced the indignity of being told off for his poor handwriting, but unlike many schoolchildren, Clayton was encouraged to work on his letters by men and women who had studied under Edward Johnston and Eric Gill, two of the 20th century’s greatest calligraphers. They had both had workshops in Ditchling, the East Sussex village where Clayton spent a lot of time in his childhood. In his twenties, he spent four years in a monastery, writing and illuminating. Then he went to Silicon Valley and advised computer companies on what to do with type.

Over the years, two convictions have grown in Clayton. The first is that in the west we have badly under-conceived what writing is. “We identify it, quite obviously, with the visible things,” he says, “the tools, the materials, the marks on the paper or whatever. But what writing really is at a deeper level is a social phenomenon, it’s a social technology. It’s made up of agreements around certain shapes that they stand for something.”

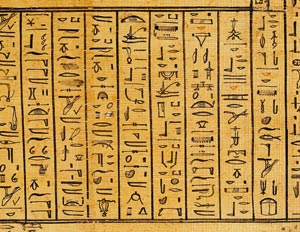

For Clayton, the story begins with mid-level Egyptian bureaucrats, around 2000BC, who began to break apart the ornate symbols of hieroglyphics into smaller, abstract strokes that could indicate consonants. (If you turn the letter E on its side, you can still see the hieroglyph of a man with his arms upraised, meaning: “You give joy with your presence.”) Pragmatism, speed, business, affairs of state: these are the forces that have driven the evolution of writing and its institutions (the library, Newton’s notebooks, the Kindle).

No way of writing ever quite supersedes another. The examples from our daily life that Clayton loves are when we suddenly notice all the forms in which we are inscribing what is in our hearts. He delights in the profusion of diaries, letter-writing and handwriting manuals in the 150 years after the invention of the printing press. He recalls 9/11: the power of the internet and the hand-drawn sign. He tells me about new character-recognising computer screens, for Indian and Chinese scripts that are easier to form by hand than type. And it fuels his second conviction, which is to look to the future of writing with excitement, rather than fear, or nostalgia. “You just see these cycles after cycles,” he says. “That’s why I am not depressed … It is constant flow, and that is because it is coming from the human condition. It is coming from us.”

…

My life in writing

by Ewan Clayton

We are at one of those turning points, for the written word, that come only rarely in human history. We are witnessing the introduction of new writing tools and media. It has only happened twice before, as far as the Roman alphabet is concerned – once in a process that was several centuries long when papyrus scrolls gave way to vellum books in late antiquity, and again when Gutenberg invented printing using moveable type and change swept over Europe in the course of just one generation, during the late 15th century.

Changing times now mean that, for a brief period, many of the conventions that surround the written word appear fluid; we are free to reimagine the quality of the relationship we will make with writing, and shape new technologies. How will our choices be informed – how much do we know about the medium’s past? What work does writing do for us? What writing tools do we need?

Perhaps the first step towards answering these questions is to learn something of how writing got to be the way it is. My own involvement with these questions began when I was 12 years old and I was put back into the most junior class of the school to relearn how to write. I had been taught three different styles of handwriting in my first four years of schooling and as a result I was hopelessly confused about what shapes letters ought to be. I can still remember bursting into tears aged six when I was told my print script “f” was “wrong”– in this class “f” had lots of loops, and I simply could not understand why.

Being back in the bottom class was ignominious. But my family and family friends gave me books on writing well. My mother gave me a calligraphy pen set. My maternal grandmother lent me a biography to read: a life of Edward Johnston, a man who lived in the village where I had my early schooling. He was the person who had revived an interest in the lost art of calligraphy in the English-speaking world at the beginning of the 20th century.

It turned out that my grandmother had known him: she used to go Scottish country dancing with Mrs Johnston, and my godmother, Joy Sinden, had been one of Mr Johnston’s nurses. “Tell me,” he had said to her in the dark watches of one night, in his slow, deliberate, sonorous voice, “what would happen if you planted a rose in a desert? I say try it and see.”

Johnston developed the typeface that London Transport uses to this day. I was soon hooked on pens and ink and letter-shapes and so began a life-long quest to discover more about writing. Several other experiences enriched this quest. My grandparents lived in a community of craftspeople near Ditchling in Sussex, founded in the 1920s by the sculptor and letter-cutter Eric Gill. Next door to my grandfather’s weaving shed was the workshop of Joseph Cribb, who had been Eric’s first apprentice.

On days off from school I was allowed to go into Joseph’s workshop, where he showed me how to use a chisel and carve zigzag patterns into blocks of white limestone. He also showed me how to cut the V-shaped incisions that carved letters are made from. I acquired a sense of where letters had begun. Then, after leaving university, I trained as a calligrapher and bookbinder and went on to earn my living in the craft. It meant I learnt to cut a quill pen, to prepare parchment and vellum for writing and to make books out of a stack of smooth paper, boards and glue, needle and thread.

In my twenties, after a serious illness, I decided to enter a monastery. I lived there for four years, first as a layman and then as a monk. I thought it would mean turning my back on calligraphy for ever, but I was wrong.

The abbot, Victor Farwell, had a favourite sister, Ursula, who had once been the secretary of the Society of Scribes and Illuminators, to which I belonged. She saw my name on the list of monks and said to her brother, “You must let him practise his craft.” So like a scribe in days of old, I became a 20th-century monastic calligrapher. But I learnt something else there also. When many hours of the day are spent in silence, words come to have a new power. I learnt to listen and read in new ways.

Finally, when I left the monastery in the late 1980s, there was one more unusual experience awaiting me. I was hired as a consultant to Xerox Parc, the Palo Alto Research Center of the Xerox Corporation in California. This was the lab that invented the networked personal computer, the concept of Windows, the Ethernet and laser printer and much of the basic technology that lies behind our current information revolution.

It is where Steve Jobs first saw the graphical user interface which gave the look and feel to the products from Apple that we have all come to know so well. So when Xerox Parc wanted an expert on the craft of writing to sit alongside their scientists as they built the brave new digital world we now all live in – somehow I became that person. It was a life-changing experience and transformed my view of what writing is. Crucial to this experience was David Levy, a computer scientist whom I had met while he was taking time out to study calligraphy in London.

So far my experience of what it means to be literate has been one of contrasts, from monastery to high-tech research centre, quill pen and bound books to email and the digital future. But throughout my journey I have found it important to hold past, present and future in a creative tension, neither to be too nostalgic about the way things were nor too hyped-up about the digital as the answer to everything – salvation by technology.

I see everything that is happening now – the web, mobile computing, email, new digital media – as in continuity with the past. Of two things we can be certain: not every previous writing technology will disappear in years to come, and new technologies will continue to appear. Every generation has to rethink what it means to be literate in their own times.

In fact, our education in writing seems never to cease. My father, who is over 80 years old, has written a letter to his six children every Monday for the last 47 years. In that time his “My Dears” have migrated from fountain pen on small sheets of headed notepaper, to biro and felt-tip; and then in the mid-seventies he taught himself to type, using carbon paper to make copies which were typed on A4 sheets. The next step was to use a photocopier for copying his originals, and today he has bought a Mac and the letters are emailed, each of my brother and sisters’ addresses carefully pasted into the “cc” box in his mail application. He is learning a new language of fonts and leading, control clicks, right clicks, modems and WiFi. Last birthday we bought him a digital camera, and his letters now contain images and short movies.

…

I wanted to piece together a history of writing using the Roman alphabet that draws together all the various disciplines surrounding it, though fundamentally my perspective is that of a calligrapher. Knowledge of writing is held in so many different places by experts on different cultures, by students of epigraphy (writing in stone) and palaeography (the study of ancient writing), calligraphers, typographers, lawyers, artists, designers, letter-carvers, signwriters, forensic scientists, biographers and many more besides.

Indeed, writing my book felt at times like an impossible task: it seemed that every decade and topic had its experts, and how could one possibly master 5,000 years’ worth of this? I have had to accept that I cannot, and instead offer a broad sweep that might lead you to explore further aspects of the story for yourselves.

In some sense, I have studied the history of craftsmanship in relation to the written word. It seems perhaps an old-fashioned concept. But as I was writing, in October 2011, Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, sadly died. All the writers reviewing Jobs’s life and work agreed on one thing: he had a passion for craftsmanship and design, and it was this that had made all the difference for Apple, and for Jobs himself.

Two perspectives seem to have been complementary to his sense of design. “You have got to start with the customer experience and work back to the technology.” And that great products are a triumph of taste. Taste comes, said Jobs, “by exposing yourself to the best things humans have done and then trying to bring the same things into what you are doing”.

One of the significant experiences in confirming Jobs’s viewpoint, it turns out, had been his exposure to the history and practice of “writing” whilst dropping out from a degree course at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Reed was one of the few colleges in North America to hold calligraphy classes. When Jobs followed his heart and took up calligraphy he was introduced to a broad sweep of cultural history and fine craftsmanship in handwriting and typography that was a revelation to him. It complemented the perspective he learnt from his adoptive father, who was a mechanical engineer, that craftsmanship mattered.

Steve Jobs was a technologist who got it, he knew that the look and feel of things mattered; that the way we interact with them was not just value added, it was part of their soul, it carried meaning, it enabled us to relate to and live with them, to bring as much of our humanity to communicating as possible. The truth is that there are many people like Steve Jobs stretching back through this history, each of whom has struggled to make communication between people a more enriching and fulfilled experience.

This is their story, and because we are the heirs to the choices they made, this story is ours also. One of the perspectives that my work has made me aware of is how young we all are in our relationship with the written word. It was only in the last century that writing became a common experience, and only in the last few decades that young people began to develop their own distinctive graphic culture.

Writing has an exciting future. Can we continue to reimagine how the world of the written word can speak to the fullness of our humanity? I say yes … try it and see.

‘The Golden Thread: The Story of Writing’ is published by Atlantic Books (£25)

Comments