Postcard from . . . St Petersburg: The Fabergé Museum

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

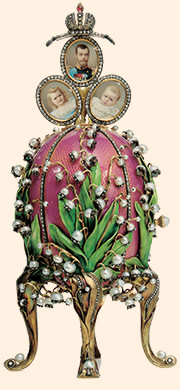

Beneath a grand chandelier in a silk-walled room in St Petersburg’s Shuvalov Palace, I bend to press my nose against a glass case. Before me is the “Hen”, the first exquisite egg created by the city’s master goldsmith Peter Carl Fabergé. It was made in 1885, commissioned by Emperor Alexander III as an Easter present for his wife, and in most museums would be the highlight of the collection. Here it is just one of many – in all there are nine eggs in the room (making it the world’s largest private collection), while the adjoining galleries contain 1,000 pieces from Fabergé’s workshops, plus a further 3,000 objects of the pre-Soviet applied arts.

I am alone in the gallery, having been afforded a preview, but even when it opens to the public next month there will be no crush – entrance will be limited to pre-booked groups of up to 15 visitors per hour. For this is a private museum, the creation of the Russian industrialist Viktor Vekselberg, whose fortune is estimated at more than £10bn.

A decade ago, as the Russian government withdrew its 30 per cent import tax on arts and antiquities, he set about realising his vision of bringing artistic treasures back to Russia. In 2004, the collection of 200 lots of Fabergé objects owned by the Forbes publishing family, including nine eggs, was about to go to auction at Sotheby’s in New York. Vekselberg pounced in advance, paying a suspected $120m to acquire them all for his homeland.

In 2006, Vekselberg secured the lease of the 19th-century Shuvalov Palace and set about a painstaking restoration to make it a setting worthy of his collection. Pre-revolution photographs showing grand society balls and dinners have been used as a guide, and today the palace’s elegant rooms are once more covered in silk wallpaper, with gilded plasterwork and elegant parquet floors.

Each egg stands on a plinth in its glass case in two orderly rows. The “Hen”, the size of a chicken’s egg, was cast in gold and decorated with white enamel. It once contained a golden hen, inside which was a crown, and a tiny ruby pendant (both now lost). So pleased with it was the Empress Maria Fyodorovna, that Alexander commissioned another the following year, and the eggs became a royal tradition continued by Alexander’s son, Nicholas II. In all, about 50 eggs were made between 1885 and 1917; 42 are still in existence.

Passing along the line, I arrive at the most valuable egg in the collection, the “Coronation”, given by Nicholas to his wife in 1897. In the proposed Forbes auction of 2004 it had been expected to fetch $24m alone. Coated in layers of yellow enamel, a difficult colour to achieve, its gold net is studded with black eagles. All the eggs contain a surprise and this one is an exact copy of the coronation coach of Catherine the Great, now held at the Hermitage.

The House of Fabergé became known across the world, employing 100 jewellers in St Petersburg and 400 in Moscow, painstakingly handicrafting a prolific output, from eggs fit for the tsars to encrusted snuff boxes for dignitaries, to cigarette cases and matchboxes. Examples of all of them are here.

One of the most valuable objects is also the most unlikely. A small figurine of a gruff-looking bearded man turns out to be one in a limited edition Fabergé series of 50 – as rare as the eggs – called People’s Types. One sold in New York last month for $5.2m. This example, the “Dancing Peasant”, is distinctly unshowy among the glitz, sculpted from natural, coloured stones. Only his tiny diamond eyes glinting back at you give the game away.

——————————————-

The Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg, opens to the public in January. Laura Ivill was a guest of Exeter International (exeterinternational.co.uk) which offers four nights at the Four Seasons Lion Palace (fourseasons.com/stpetersburg) including airport transfers, flights from London, two days with a private guide, driver, from £1,780. Exeter can add tickets for the Fabergé Museum for £70 per person

Comments