Britain: A time to lead rather than leave the EU?

Some bits of history cannot be left behind. The first act of the psychodrama that is Britain’s European referendum campaign opened in the early months of 1960. The nation had lived through a decade of drifting decline. A last imperial hurrah at Suez had ended in humiliation as the geopolitical map was redrawn by the superpower rivalry of the US and the Soviet Union.

Across the channel, enemies had become friends in the Franco-German common market. Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government decided it was time to take a hard look at the world. Its conclusion — that Britain could not remain aloof from events on its own continent — began the argument now raging.

Crystallised then, the essential elements of Britain’s European debate have not changed. Macmillan’s application to join the EU — it would take 13 years before another Tory prime minister, Edward Heath, realised the goal — foretold most of today’s arguments. Behind the debates about the economy and immigration lie neuralgic concerns about history, self-image and identity; about the tension between collective decision-making and abstract notions of sovereignty; and about the competing horizons offered by Europe and the wider world. They are also about how deep emotions can collide with the harsh facts of economic and political life.

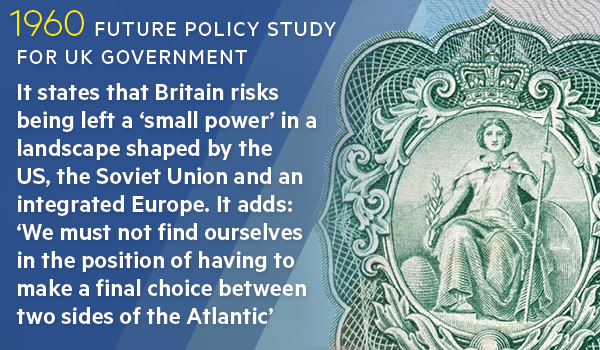

Macmillan commissioned his advisers and mandarins to take stock of the components of British power, economic and military, and then peer a decade into the future.

Where, he asked, would the nation that had so recently ruled much of the world stand in 1970? Chaired by Norman Brook, the cabinet secretary, and conducted in great secrecy, the Future Policy Study was delivered in February 1960.

Numbered copies, stamped “top secret”, were distributed only to Macmillan’s most trusted colleagues. The conclusions were brutal. Britain could no longer keep up the pretence of being a great power on a par with the US and Soviet Union. The coming years would herald further relative decline and Britain’s global responsibilities would run further ahead of its economic capacity.

After the humiliating failure four years earlier of the Anglo-French enterprise to seize back control of the Suez Canal, the authors were unequivocal about the importance of a “special relationship” with Washington. Britain’s future status would depend on America’s “readiness to treat us as their closest ally”. But serving as Greece to America’s Rome was not enough. Three years after the signature of the Treaty of Rome, France, Germany and four continental partners were making a success of the common market.

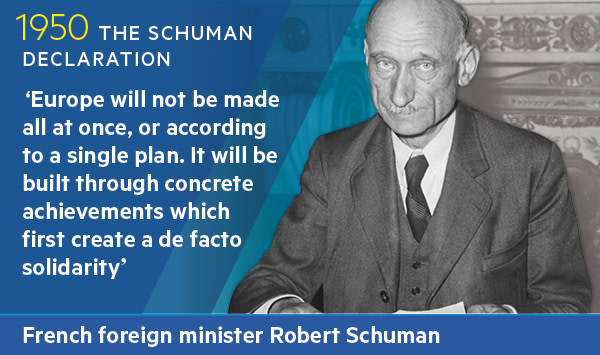

The prevailing view among British ministers and mandarins throughout the 1950s had been that the European project that had begun with Robert Schuman’s plan for a coal and steel community would never properly happen.

When in 1955 officials of the six nations — the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Italy alongside France and Germany — gathered at Messina in Sicily to talk about a common market, Whitehall and Westminster had been dismissive.

Rab Butler, the then chancellor, caught the mood in describing Messina as some “archaeological diggings . . . in an old Sicilian town”. British diplomacy could derail such projects.

The message of the Future Policy Study was that this strategy had failed. Germany was emerging again as Europe’s economic powerhouse and the common market had rendered irrelevant the rival trading arrangement — a European Free Trade Association including such nations as Sweden, Denmark and Portugal — favoured by Britain. For the first time since the Napoleonic era the European powers were excluding Britain from a continental enterprise.

What was needed was a balancing act, matching Britain’s vital security relationship with Washington with engagement in Europe. “Whatever happens,” the report said, “we must not find ourselves in the position of having to make a final choice between the two sides of the Atlantic.” Within six months of receipt of the study, Macmillan decided to lodge Britain’s bid to join the European Economic Community.

If the Suez debacle had put paid to imperial delusions, it had not banished the impulse that said Britain’s outlook should be global. The national myth, crafted by the Victorians as an explanation for the inevitability of the British empire, celebrated English exceptionalism. There would always be a measure of fog in the channel.

‘Outdated terms of a vanished past’

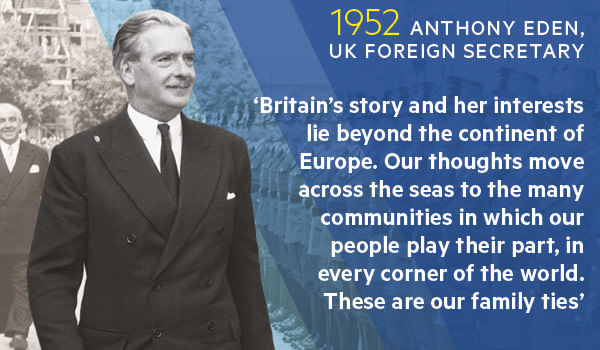

Even as the empire dissolved, Britain looked to the world. Anthony Eden, whose premiership had foundered on the rocks of Suez, gave voice to the mindset: “Britain’s story and her interests lie beyond the continent of Europe,” he said in 1952. “Our thoughts move across the seas to the many communities in which our people play their part, in every corner of the world. These are our family ties.”

The echoes can be heard today in the expansive rhetoric of Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, Conservative leaders of the Leave campaign. To restore itself to global leadership all Britain needs to do is unshackle itself from Brussels.

Macmillan dismissed this as nostalgia before Messrs Johnson and Gove were born. “In the past, as a great maritime power, we might give way to insular feelings of superiority over foreign breeds . . . But we have to consider the state of the world as it is today and will be tomorrow, and not in outdated terms of a vanished past,” he said. “Foreign breeds” is not a phrase a politician could use today, but it captured the assumption of superiority that still infuses the arguments of Tory nationalists.

Charles de Gaulle, France’s president, sided with Eden, scuppering Macmillan’s application for membership. “England in effect is insular,” he said. “She is maritime, she is linked through her exchanges, her markets, her supply lines to the most diverse and often distant countries.” De Gaulle thus anointed himself Britain’s first Eurosceptic.

The supposed choice — Europe or the world — is still posed. Today’s Brexiters hanker after Elizabethan glories, reimagining Britain as the footloose privateer leaving Europe behind to make its fortune in far-flung lands. Ask them about trade with Europe and they talk about the deals to be made instead with India or China, about revitalising the so-called Anglosphere of the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and about refurbishing ties with the nations of the Commonwealth. Economics, they believe, is nothing against such dreams.

The harsher reality, political and economic, has been heard during the referendum campaign from US President Barack Obama and other friendly nations. This is not an either/or choice between Europe and the world. Rather, engagement in Europe amplifies Britain’s voice on the global stage; retreat from its own continent would leave the nation in unsplendid isolation.

The second enduring neuralgia turns on the issue of sovereignty. Parliamentary democracy is viewed as a uniquely British invention. Signing up for Europe means pooling decision-making. Lord Home, Macmillan’s foreign secretary, understood this clearly in 1961: “Let me admit at once that the Treaty of Rome would involve considerable derogation of sovereignty.” But how could England, the mother of parliaments, surrender control of any of its laws to continental partners whose experience of democracy was slight by comparison?

Enoch Powell, the Tory MP and former minister, made English nationalism his own. For Powell, the Treaty of Rome mocked the basic liberties of Shakespeare’s scepter’d isle and threatened to pull down the very pillars of self-government. Of the six nations that had signed the treaty, Powell noted, four had come into being during the past two centuries. Contrast that with England’s stately constitutional progression.

Powell added a second dimension to this Tory nationalism by mixing nostalgic exceptionalism with the crude politics of identity. The immigrants of the 1960s arrived from the former colonies rather than eastern and central Europe, but the basic argument was the same. To Powell, England was surrendering its freedom to Brussels even as its culture and mores were being overwhelmed by outsiders. The message is familiar to anyone following the present campaign. Expansive they may be about Britain’s global reach, but today’s Brexiters also want to slam the door on outsiders. Hence the mendacious warning of a new tide of immigration when (it should be “if”) Turkey gains admission to the EU.

‘The wrong people are cheering’

Euroscepticism has never been the sole property of Conservatives. Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour leader, saw political advantage in opposing Macmillan’s plan. Joining the EEC, he told his party’s annual conference in 1962, would mark “the end of Britain as an independent European state. It means the end of a thousand years of history.” The applause was thunderous. The Labour leader’s wife Dora was unimpressed. “All the wrong people are cheering,” she told her husband. The observation comes to mind as Mr Johnson makes common cause with Nigel Farage of the anti-immigrant UK Independence party, and George Galloway of the hard-left Respect party.

The sovereignty question can be answered by distinguishing substance from symbols. Real sovereignty represents the capacity to act. The sovereignty sought by the Leave campaigners is the freedom to shout angrily from the sidelines. So why, half a century later, do the British people still have to be persuaded to remain within the EU? The arguments used by David Cameron, the prime minister, are, after all, little different from those deployed by Heath in 1973 and ratified in a referendum two years later.

The pro-European camp has made its case forcefully enough, although hyperbole about economic Armageddon and international isolation has sometimes undermined rather than strengthened the case. Surely it is enough to say that the nation is more prosperous and secure in partnership with its neighbours — and would thus be poorer and more vulnerable outside? The Remain camp’s calculation is that when voters cast their ballots on June 23 they will vote, as in 1975, for hard-headed realism over the tugs of history and emotion.

Perhaps they will. But the unanswered question is why, after more than four decades of membership, the outcome is in any doubt. Beyond psychoanalysis, one part of the explanation is that the Brits have never seen the EU through the same lens as its partners. For France and Germany, Europe was the answer to war; for Spain or Portugal, the escape route from fascism; for eastern and central Europe the guarantor of freedom. Britain, though, finds it hard to forget that it “won” the war, and that, since 1066, it has never been conquered by a hostile army.

The temper of the times — a national mood that since the 2008 financial crash has grown disgruntled with austerity and ever less trusting in the political establishment and business elites — also favours those who want to leave. Add to the mix stagnant household incomes, the excesses of the 1 per cent and the economic and social disruption caused by immigration and the Brexiters have fertile ground for their populism. The Leave campaign is as much about harnessing popular rage against the economic insecurities and open borders of globalisation as about defenestrating the Eurocrats of Brussels.

A moment to lead

A harsher truth is that even those British politicians who have always declared themselves pro-Europeans have been deeply reluctant to make anything that amounts to a pro-EU case. The British approach to the union has always been instrumental and transactional. Politicians have found it much easier to claim to have won a victory around the council table in Brussels or secured an opt-out from an unpopular policy than to present the EU as a guardian not only of common interests but also of shared liberal democratic values. Britain, after all, had stood alone in 1940.

“The paramount case for being in,” Margaret Thatcher, newly appointed as Tory leader, observed during the 1975 referendum campaign, is “the political case for peace and security.” Sadly, such sentiments were forgotten by the Lady once she was given the chance to swing her handbag in Brussels. Britain never signed up to the political idea of Europe. Generations of politicians have insisted it agreed only to a common market.

In 1960, the post-imperial nostalgia was readily explicable. Power had only recently slipped away. Britain needed time to adjust to a world in which its influence, though still considerable, was that of a great nation rather than a great power. The Brexiters cannot let go. For them, Brussels has become the millstone holding Britain back from recovering past glories.

Another set of memories, however, has shortened. The ugly nationalism, the economic chaos and the political fragmentation that saw the Europe of the first half of the 20th century collapse into terrible violence have receded. You could say this is testimony to the extraordinary success of the European project in burying past enmities and promoting prosperity and security.

Yet the continent’s present troubles should serve as a reminder of its capacity for self-harm. The rise of populism, drawing from the well of economic and social discontent, carries disturbing echoes of the 1930s. A confident Britain would see this as a moment to lead rather than leave. But perhaps the best that can be hoped of the referendum is that the British will decide finally that the time has come to actually “join” Europe.

Comments