Sin wins investor battle of vice or virtue

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

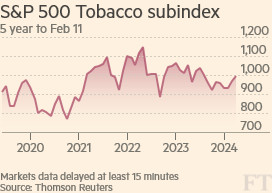

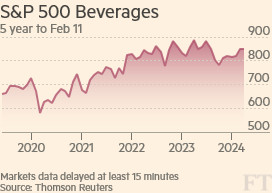

Sin works. The long-term numbers, produced this week by the London Business School academics Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton for the annual Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook, showed that tobacco and alcohol stocks have led the US and UK stock markets respectively over the sweep of history since 1900. They were dramatic, but not surprising. Most people know that companies that sell addictive drugs enjoy a strong franchise and can reliably churn out high cash flows.

The question is what to do about it. Can investors profit from this insight? And, as many pension funds and charitable investors understandably regard it as part of their mission to combat the social ills caused by alcoholism and smoking (and in some cases gambling, pornography and weapons as well), can they do something about it?

The investment industry’s attitude to the issue shows uncharacteristic restraint. There is only one well-known mutual fund that specialises in vice stocks. Rather than embrace its status, it recently changed its name from the Vice Fund to the less offensive Barrier Fund.

One exchange traded fund has tried to tap the ongoing strength of sin stocks, and failed. The FocusShares ISE SINdex fund, investing in 20 equal-weighted US stocks drawn from alcohol and tobacco producers and casino operators, came with a catchy name and a clever ticker symbol (PUF). It was launched in 2007, when sin stocks’ defensive characteristics should have had some appeal. But it failed to gain much interest and did not survive the post-Lehman crash: it was wound up in October 2008.

These episodes suggest few people have the appetite to call a spade a spade and openly embrace sin investing. It is unlikely that sin investing, packaged that clearly, will ever be very popular.

That in turn implies sin investing should continue to pay off. Shunning sin stocks reduces their price, and pushes up their dividend yield. The S&P 500 tobacco sector currently trades at a dividend yield of 4.23 per cent, more than double the market yield of 1.97 per cent. The S&P’s casino sector, represented by Wynn, has a dividend yield of 4.06 per cent.

These yields, as the history of the past 115 years demonstrates, are reliable. They are supported by addicts who need to keep paying for their products. Long-term investors do not need the discount on these stocks to narrow in order to make money — they can simply enjoy the yield as it mounts up year on year.

On this measure, the sum impact of ethical funds that eschew the sin sectors has been to push up the returns for those less scrupulous.

What of the trickier question of encouraging virtue? For many investors, given their statutes, some financial underperformance may be acceptable — providing they can show that their policies succeed in furthering their trustees’ social aims. But in practice this is difficult to do.

The “exit” strategy of avoiding sin stocks does not seem to work. The Vanguard FTSE Social Index fund, launched at much the same time as the Vice Fund to invest only in socially responsible stocks, has since August 30 2002, turned $1,000 into $2,679. This is behind the index and far behind the Vice fund, which would now be worth $3,366. It is not clear that the screening approach has done anything more than make sin stocks — which appear to outperform in virtually every market that the academics could measure — cheaper for everyone else.

But a “voice” strategy, borrowing tactics from corporate activists, of using a position as a shareholder to agitate for corporate change, does seem to work. Research on a large investment fund by Prof Dimson found that a year after “engaging” with a company, the average extra return — after accounting for factors such as the market return and the size of the company — was 2.3 per cent. The positive returns from provoking an improvement in social factors was roughly equivalent to the returns generated by engineering improved corporate governance, an area where such activism tactics are already widely used.

This suggests that a “washing machine” strategy might work. Big funds with a mandate for social responsibility should buy the stocks of irresponsible companies, and work to make them behave better. That way they will generate a good return for their investors, while also fulfilling their trustees’ social aims.

That appears to be the moral of the tale. Those investors charged with doing good can do so, but they will need to work hard and shake up their companies.

If socially responsible investing remains focused more passively on screening out stocks that are deemed distasteful, the logical response — from those whose trustees will permit it — is to be grateful that sin stocks’ price has been pushed down, and buy them.

Comments