The eurozone: A strained bond

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In his tumultuous time as president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi has always been able to rely on the unequivocal support of German chancellor Angela Merkel. Not any more.

The mutual trust between Europe’s most important central banker and its most powerful political leader will this week be put to the test as the ECB unveils its long-awaited quantitative easing package in the face of serious German reservations about the central bank buying government bonds.

Berlin will not publicly oppose the package that Mr Draghi is expected to unveil in Frankfurt on Thursday. But it is pressing for tough conditions which the ECB fears could limit its chances of success. “We have made it clear that it is questionable to do QE,” says one person with a knowledge of government thinking. “Draghi talks to people in Berlin. He knows what is going on in Germany.”

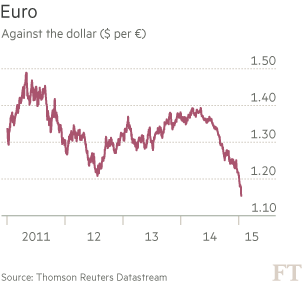

The stand-off comes at a critical time for Germany, the eurozone and the EU, with the economy stagnant, unemployment high and the union’s reputation as a global economic powerhouse at stake. The euro last week touched an 11-year low against the dollar after the Swiss central bank’s decision to drop the cap on the franc removed from the market a big buyer of euros. Next Sunday, voters go to the polls in debt-laden Greece, the eurozone’s most vulnerable member, in an election which could determine its future in the eurozone.

With the fall in oil prices pushing the region back into deflation for the first time in five years, Mr Draghi sees QE as a powerful weapon in his fight against a long-lasting bout of falling prices that would plunge the region into economic depression.

It would also boost the collective power of the EU’s central institutions, not least the ECB, and help show the world and sceptical European voters that the union remains more than the sum of its parts.

Yet events in Greece — where the leftist Syriza party, which is calling for a national debt restructuring, is expected to win — have underlined German concerns about QE, above all the fear that German taxpayers might have to take the hit for spendthrift member states. At the same time, Ms Merkel is not as convinced as she was at the peak of the eurozone crisis that the economic danger is so acute that she has to back Mr Draghi at any cost. “At this time [Ms Merkel] is more sceptical. My impression is that she has some doubts about whether QE will work,” says a senior MP from the chancellor’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU).

Room for compromise

The ECB president last week met Ms Merkel and Wolfgang Schäuble, her powerful finance minister. Mr Draghi will almost certainly compromise on elements of his package of government bond purchases to appease the German public. But resistance is so fierce that this might not be enough. And by bowing to Berlin, Mr Draghi risks announcing plans that would disappoint markets and destroy the ECB’s biggest chance to spur the region towards a meaningful recovery. “Markets need to view any QE package as a continuation of monetary policy and not something which is constrained by the peculiarities of the eurozone,” says JPMorgan strategist Stephanie Flanders.

But for most Germans, QE is not the answer to the economic weakness of the eurozone’s more vulnerable members, with some believing it is a threat to the common currency’s financial stability. With long memories of the dangers of inflation dating back to the 1920s, Germans are scared that unleashing more liquidity into the already saturated eurozone economy will eventually trigger a horrendous price surge.

Moreover, many Germans say monetary easing will postpone painful spending and borrowing cuts by giving weak states more financial wiggle room.

At Thursday’s vote, the ECB president will not be able to count on the support of the two top Germans at the bank — Jens Weidmann, Bundesbank president, and Sabine Lautenschläger, ECB executive board member. Mr Draghi will almost certainly win a majority on the board. But even if he secures unanimous support for QE from central bank governors in the rest of the 19-member eurozone, it will not help him in Berlin — the dissent will encourage other German critics and exacerbate the challenge of winning over opinion in the currency area’s most powerful nation. From its Frankfurt headquarters, just miles from the ECB’s new building, the Bundesbank has led the charge against QE.

Mr Weidmann, a former adviser to Ms Merkel, has said openly the policy would do little to lift the region’s economy and could delay reform. His views are shared by Mr Schäuble, who has made clear his irritation with monetary easing, saying in a Bild newspaper interview that “cheap money” should not sap the willingness to execute reforms.

German opposition

What Mr Weidmann says matters: the German central bank holds the status of national treasure for its staunch defence of the Deutschemark in the 1970s, which helped produce decades of low inflation and strong growth before the introduction of the single currency. Clemens Fuest, president of the ZEW think-tank, says: “The Bundesbank for Germans is a symbol of solidity.”

Yet, for all its homegrown popularity, the Bundesbank has been sidelined at the ECB’s top table. Mr Weidmann’s predecessor Axel Weber resigned over an earlier bond-buying scheme, the securities markets programme, along with his fellow German Jürgen Stark, then the ECB’s chief economist.

There is no suggestion that the current Bundesbank chief or Ms Lautenschläger will quit, should the ECB launch QE on Thursday.

“The ECB was said to be constructed in the shape of the Bundesbank, and that was why Germany accepted one vote per member state,” says Hans-Werner Sinn, head of the Ifo think-tank in Munich. “Now the Bundesbank is being pushed into a minority on all the big decisions.”

The Bundesbank’s loss of influence has fed fears that the ECB will force Germans to pay for others’ profligacy. “The key difference in QE here, and not the UK and the US, is that the eurozone is a monetary union,” says Mr Fuest. “People talk about deep cultural difference, but that’s not the main issue here. If we had the same economic situation and no euro, I don’t have the slightest doubt that the Bundesbank would do QE.”

Any compromise between the ECB and Berlin has to focus on QE’s details, as Mr Draghi seems certain to press ahead with the plan itself.

FT Video

Alberto Gallo on why monetary easing alone won’t reflate eurozone

Recent discussions have focused on the timing, scale, and nature of the programme. Berlin would prefer purchases of short-term sovereign bonds, not long-term debt which it views as more like fiscal support. It also wants the ECB to buy bonds from all countries, and not just weak southern states, as this would also smack of budgetary assistance.

More controversially Mr Weidmann has signalled that he would be less critical of a QE programme which placed the burden of losses on national central banks. Anything else would “lead to a redistribution of risks between taxpayers in the member countries”, he said in December. Mr Draghi looks set to bow to the Bundesbank president’s request, as well as Berlin’s demand that debt purchases are focused on bonds with shorter maturities.

But shouldering national central banks with responsibility for any credit losses from their national bonds would damage the appearance of cross-EU solidarity. Earlier crisis-fighting schemes have seen a commitment to share losses, and to break with that principle now would suggest the ECB is not as committed to monetary union as it once was. However, market economists would prefer a compromise on burden sharing, rather than Mr Draghi being forced to back down on the size of a package.

Federal Reserve-style open-ended bond purchases, with a commitment from the ECB to keep buying until inflation is on course to hit the target of 2 per cent, is viewed by many investors as the most credible form of QE. But a small package of below €500bn would disappoint markets, even if the risk of any possible losses were to be shared.

Der Spiegel, the German magazine, reported that Greek bonds would be excluded from QE. A likelier option is for Greece to be included, as long as Athens remains in a European Commission reform programme.

Reform push

Ms Merkel’s officials judge that the eurozone is now in better shape to withstand a possible argument between Berlin and the ECB than it was in 2012. That was when she backed Mr Draghi after he said he would do “whatever it takes” and announced the Outright Monetary Transactions programme to save the euro. They believe more ECB support will not help, as weak economies need reform not more money. Berlin also fears QE will relieve the pressure not only on Greece but also France and Italy to pursue structural reform.

In an ideal world, Berlin would like a measure of QE to be married to a package of revitalised reform pledges supported by the European Commission. Its officials will not give up pressing Athens, Paris and Rome for fiscal and structural reforms, including spending cuts. Mr Draghi has also called for more power to be handed to Brussels to force countries to undertake painful reforms.

A political worry for Ms Merkel is the rise of the eurosceptic Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which narrowly failed to get into parliament at its first attempt last year but has since won seats in the European parliament and in regional assemblies in east Germany. It is campaigning for its first west German regional seats in elections next month.

Despite the danger, most top politicians of the conservative CDU/CSU coalition will probably be discreet in their comments. But some will break ranks.

A key political sceptic is Peter Gauweiler, a CSU veteran who once condemned the euro as “Esperanto money”. A wealthy lawyer, he has led several unsuccessful attempts to have the German constitutional court block measures that enhance the EU’s powers at the cost of national sovereignty.

This month, he suffered his latest setback when the European Court of Justice’s advocate general advised that the ECB was broadly within its right to conduct OMT. But it is unlikely to stop German critics continuing the legal fight.

Christoph Degenhart, a Leipzig law professor who co-operates with Mr Gauweiler and others in the court cases, told the Financial Times the group would likely open a new front over QE, once it was announced. “The ECB is exceeding its mandate. This is not monetary policy. It is support for weak economies.”

The German media are likely to be hostile. Commentators tend to criticise the ECB, sometimes virulently, with the financial weekly WirtschaftsWoche condemning low interest rates as a “diktat from a new Banca d’Italia, based in Frankfurt” — a reference to Mr Draghi’s Italian citizenship.

An ECB charm offensive has seen the usually media-shy president give interviews to German media. But PR will not win the day just yet. Marcel Fratzscher, head of the DIW think-tank and a former ECB official, says: “ A big majority of economists and journalists won’t like [QE]. Very few will support it.”

With Ms Merkel silent, the burden of getting the QE package right and selling it to Germany’s sceptical public rests with the ECB president. A senior CDU MP says: “Ms Merkel will let Mario Draghi do his job. It means he takes on the risks involved and she does not.”

***

History lesson: Where deflation is not part of the narrative

Germans have been treated to an unusual charm offensive by the European Central Bank in recent weeks, with Mario Draghi granting interviews to the local press. But it is unlikely to dent the hostility Germans feel towards the ECB. The country has long used its economic history to push the virtues of frugality. That narrative is so strong that the quantitative easing programme sought by the ECB chief will remain unpopular.

“I hesitate to go back to the 1920s but, after the first and second world wars, Germany found out that when central banks financed state spending, it destroyed the currency,” says Jörg Krämer, chief economist at Commerzbank. “The experience of hyperinflation is somewhat in the DNA here, so Germans do not want to see the ECB buying government bonds.”

The destruction of the Reichsmark’s value is an important historical lesson. But missing from that narrative is the painful deflation that followed hyperinflation. In 1923, at the height of the hyperinflation, 751,000 Germans were without work. By 1932, as deflation began to bite, unemployment hit 5.6m.

“There is a strand of historical thinking that the hyperinflation of the 1920s prepared the German people for the rise of Hitler, when in fact the Weimar Republic survived that but not the deflation of the early 1930s,” says Adam Tooze, an economic historian at Yale University.

While Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s seminal text, A Monetary History of the United States, has helped ensure the US policy mistakes that led to deflation are remembered, there is no equivalent in Germany.

Clemens Fuest, president of the ZEW think-tank, says: “The emergence from the depression in Germany was very different to that in the US or the UK. We didn’t have a narrative of terrible deflation, which exists elsewhere.”

The postwar success of West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s, under the “ordoliberalist” economic doctrine, strengthened the reputation of the view that politicians and central bankers are there to maintain order, not boost demand.

Comments