AB InBev: one more deal for the road?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A pint of beer contains a lot of water — but even more money. The latter observation set Jorge Paulo Lemann on a path to become one of the world’s richest men with a $25bn fortune, according to Forbes.

“I was looking at Latin America and who was the richest guy in Venezuela? A brewer. The richest guy in Colombia? A brewer. The richest in Argentina? A brewer,” the Rio de Janeiro-born financier said in 1989. This was when he and his Brazilian partners — Marcel Telles and Carlos Alberto Sicupira — bought control of Brahma, a Brazilian brewer, despite knowing little about the sector.

A couple of decades on, Mr Lemann had indeed become Brazil’s “richest guy” thanks to his 12.5 per cent stake in AB InBev, the world leader that Brahma became. The Brazilian trio drove Brahma’s transformation into a company with a 21 per cent global market share through a series of ever-bolder deals, culminating in a $52bn takeover of Anheuser-Busch, owner of Budweiser.

They got there by following, with discipline and tenacity, their own mantra to “dream big”, accompanied by a driven and demanding management style, described in the first instalment of this two-part series of articles. But where do you go once “dream big” turns into a reality and you have become the biggest?

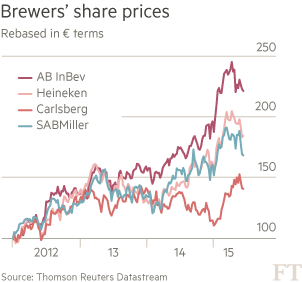

That is precisely the challenge facing AB InBev today. With a market value of €170bn, it is larger than each of HSBC, Bank of America and Walt Disney. Only a mega-merger would make a difference to its scale. The most frequently speculated targets would cost $90bn or more (see box below). But the bigger the deal, the bigger the execution risk.

The alternative is to grow organically, in spite of the fact that consumers are not drinking more beer in the mature US market, AB InBev’s biggest for beer. Budweiser, the brew that Carlos Brito, AB InBev chief executive, calls “America in a bottle”, is at the heart of that task.

Crafty competition

The Anheuser-Busch brewery is a red-brick fortress in St Louis, Missouri, close to the Mississippi river. Built in 1852, it is the biggest AB InBev brewery in the US. More than 500,000 tourists a year come to see how Budweiser is made and visit a slice of American heritage that includes white-socked Clydesdale horses — a reminder of bygone days.

Part one of the series

AB InBev’s hard-nosed kings of beer

Andrew Hill and Scheherazade Daneshkhu gauge the brewer’s demanding culture through interviews with current and former executives, staff, analysts, consultants — and critics

Over a hamburger and the recently launched Budweiser Signature Draught — it has a creamy, rather than foamy, head — Jorn Socquet, AB InBev’s vice-president for marketing in North America, explains the challenges of getting the brand back into growth.

The self-titled “king of beers” is growing internationally but in the US plays second fiddle to Bud Light, a spin-off brand launched in 1982. Sales of Budweiser have been in decline in the US for decades but what really rankles is that it is now outsold by Miller Lite, brewed by MillerCoors — a joint venture between the UK’s SABMiller and Molson Coors of the US.

“We were perfectly OK being the victim of the success of Bud Light because its growth more than offset the decline of Budweiser. But as soon as that stops, you are getting into trouble, which is why it’s so important for us — even if it’s small single-digit growth — to return to growth for Budweiser,” the 41-year old Belgian says.

Younger consumers have flocked to little-known craft beers, bourbons and cocktails, leaving mainstream beer in decline, a trend that causes Mr Socquet to lose sleep. “What keeps me up at night is, how do we genuinely reconnect with the new generation of people that is agnostic to brands?” he says.

Having already bought craft beers such as Goose Island and Shock Top in response to the trend, AB InBev is also making its biggest brand investment to date in Budweiser this year. This includes rolling out Signature Draught across the country; it gives bars a “significant” sales boost, says Mr Socquet .

The marketing message is changing too. The latest Super Bowl adverts emphasised heritage and consistency — “brewed the hard way” — to take on craft beers, which now account for 11 per cent of the market, up from 5 per cent in 2010, according to the Brewers Association.

Mr Socquet has high hopes for the recent launch of bold packaging emblazoned with the Statue of Liberty. Another change is to move some of the marketing team from St Louis to New York to be closer to urban trendsetters.

Park Avenue parsimony

AB InBev’s New York offices are on Park Avenue, a swish address for a supposedly frugal company. But the rental agreement was struck during the financial crisis in 2008 and the open plan office is confined to one relatively small floor.

The off-white desks have seen better days. They have little on them and are strikingly tidy — “we are encouraged to clear up at the end of the day,” says one employee — but there are no signs of little stickers marking the ideal placement of telephone and penholder recounted by one former employee. The door of the stationery cupboard is also open in an apparent contradiction of tales that the ferociousness of the cost-cutting culture means staff have to buy their own pens and paper.

Luiz Fernando Edmond, AB InBev’s head of sales, gets up from the central desk he shares with Mr Brito and other senior executives to walk into one of the small meeting rooms behind a bar and kitchenette.

Here, he admits in an interview that “we don’t have a magic formula” to get Budweiser back into growth in the US but adds that its decline has been stemmed. “It would be very easy for us just to say the trends will continue, that it’s not our fault; it’s whatever happened in the past. But we said, no, we don’t accept that. We said we need to fix Budweiser in the US.”

The need to increase sales organically is not just an issue for Budweiser. Across its brand portfolio, AB InBev is constructing “growth development platforms”: strategies to boost sales based on identifying beer-drinking occasions. These range from social media marketing campaigns to Belgian chefs appearing at food festivals to talk about menus suited to Stella Artois beer. “We are now spending a lot more time in trying to understand how we can grow the top line globally,” says Mr Edmond.

‘The supreme acquirer’

Yet M&A would be a far quicker route to growth judging by past spectacular results. In 1992, Brahma had a market value of $830m; today AB InBev’s market capitalisation is about 230 times bigger, according to FactSet. Coca-Cola’s tripled over the same period. AB InBev is “the supreme acquirer”, according to Goldman Sachs, which forecasts a $145bn transaction by the end of next year.

Its strategy of making acquisitions and cutting costs led to $3.5bn in synergies in its last three mergers — more than the combined total of synergies from all other brewing transactions in the last decade. The result is an efficiently profitable business. AB InBev’s operating margins are the highest in the industry at 32.5 per cent, up from 23.3 per cent in 2008, when AB was bought.

These achievements have secured a ringing endorsement from Warren Buffett, the world’s most respected investor, for the men he calls “the Brazilians.” Mr Buffett has put his money where his mouth is by investing through his Berkshire Hathaway investment group with 3G Capital, the private equity group co-founded by Mr Lemann, Mr Telles and Mr Sicupira 11 years ago.

Mr Buffett and New York-based 3G appear set on replicating in US food what AB InBev has done in beer, by buying Burger King in 2010, Heinz in 2013 and Kraft Foods this year. “3G does a magnificent job of running businesses,” Mr Buffett has said.

Having Mr Buffett as an ally potentially widens the scope of targets. So far, though, the Brazilian trio have kept their (privately-held) 3G investments legally separate from AB InBev, in which the three men hold a 22.7 per cent stake. They are the second-largest shareholders after the Belgian former Interbrew investors that hold 28.6 per cent of the shares.

‘Way more action in China’

On average, AB InBev has merged every four years over the past 16 years. The last sizeable takeover was three years ago and debt is being repaid fast to a level at which the company will either start returning cash to shareholders or gearing up for a big deal.

Mr Brito, the Rio-born 55 year-old at the helm of the company, insists that deals are not essential to the company’s growth but it is questionable whether organic growth alone will satisfy the company’s ambitious managers.

In an interview in New York, Mr Brito says the company will look at M&A so long as the target, deal structure and price make sense but does not feel any pressure to do deals. “We’re not building a dream that has to have M&A, we’re building a dream about company growth,” the CEO declares.

Asked whether AB InBev would look at targets outside the beer sector — perhaps soft drinks (PepsiCo, Coca-Cola) or spirits (Diageo) — Mr Brito, who dislikes unwieldy conglomerates, repeats his preference for “near beer.”

The group is virtually absent from Africa — the world’s fastest-growing beer market and a stronghold for SABMiller — but Mr Brito says he prefers China, where AB InBev has an 18 per cent market share.

“Asia offers an amazing opportunity for growth just like Latin America. There is way more action and dynamic in China than in Africa,” he says. “We believe a lot in focus so if we open too many fronts, it’s just hard to do it right.”

Such remarks are ambiguous enough for the speculation surrounding the group’s M&A ambitions to continue.

One certainty, however, is that AB InBev will keep moving. “The way we’ve built our company has always been with this constant dissatisfaction about our results and our achievements . . . so we’re never happy with where we are,” says Mr Brito. “We always think we can do more.”

To read the first article in this series visit ft.com/abinbev

Comments