Middle England drives Brexit revolution

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ann Potts has insurrection on her mind. With her elegant twin-set, pearl necklace and the clipped tones that betray a life spent in and around the British military, the 72-year-old does not resemble a revolutionary in the least. But today she is pacing the streets of Bracknell, a town in prosperous Berkshire, trying to win over local shoppers to a distinctly anti-establishment message.

Together with fellow activists from Bracknell4Brexit, a local campaign group, Ms Potts is telling passers-by to ignore what the prime minister says, ignore what the Bank of England says, ignore what the US president says — and vote for a British exit from the EU in next week’s referendum. “We want to be our own people,” she says.

In 1975, when Britain held a referendum on membership of the European bloc, she voted in favour (“Because I listened to all the rubbish they told us!”). But the decades since have darkened her feelings both for the EU and for the political establishment. “I trust political leaders less than I used to,” she says. “They have not been honest with themselves, and they have not been honest with the people.”

Ms Potts is far from alone. To millions of voters up and down the country, the referendum campaign has brought home just how little faith they have in Britain’s politicians and parties, business lobbies and trade unions, think-tanks and investment banks.

Along with bodies such as the International Monetary Fund and the OECD (not to mention President Barack Obama ), they have all issued stark warnings against Brexit.

But their interventions have done little or nothing to stop the Leave camp from pulling into the lead in recent polls.

“For some, this is simply a vote against the establishment,” observes Justin Bellhouse, the spokesman for Bracknell4Brexit. Like other Brexit campaigners, Mr Bellhouse reels off a list of scandals and broken promises — from government vows to clamp down on migration to a 2009 parliamentary expenses scandal. “It’s about the blatant lies. When the lies just keep on coming people say: how can I trust these people any longer?”

The rise in anti-establishment sentiment goes far beyond the UK — as shown by support for Donald Trump in the US presidential race and advances made by populist movements on the left and the right throughout continental Europe.

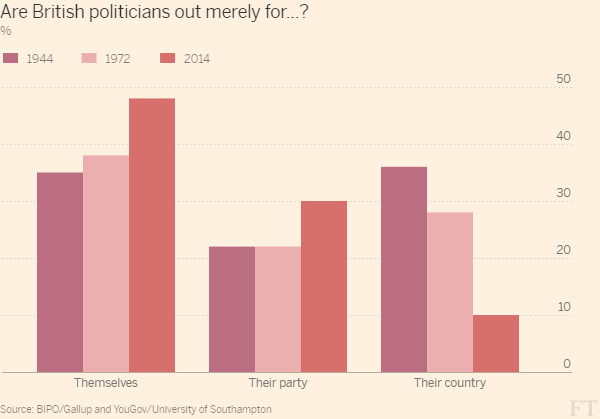

Neither is mistrust in politicians a new phenomenon, argues Will Jennings, a professor of politics at Southampton University. He has studied British attitudes towards the political establishment since the 1940s. The conclusion: trust has eroded steadily over decades, but is now running alarmingly low.

The UK’s Mass Observation archive, which collects diaries and other private correspondence, shows that people today write about doctors, the clergy and lawyers in more or less the same way as they did back in 1945. That is not the case with politicians, as a recent paper co-authored by Professor Jennings points out: “Citizens now described their ‘hatred’ for politicians who made them ‘angry’, ‘incensed’, ‘outraged’, ‘disgusted’ and ‘sickened’.”

Among the words used for politicians, the paper adds, are arrogant, boorish, corrupt, creepy, devious, loathsome, lying, parasitical, pompous, shameful, sleazy, slippery, spineless, traitorous, weak and wet. As Prof Jennings says, “whatever measure you use political mistrust is rising — you see a generalised malaise”.

Dr Phillip Lee, the Conservative member of parliament for Bracknell, offers a curious illustration of the trend. Aside from his parliamentary duties, he continues to practise as a doctor — still one of the most trusted professions. He quips that on days when he does medical work in the morning before heading to Westminster for a vote: “I can feel the trust ebbing away in an afternoon.”

Dr Lee adds that “there is a fundamental breakdown in trust not just between voters and politicians but also with the BBC, the Bank of England, the City of London and so on. Where do you find truth these days?”

Oft-cited causes of this breakdown range from high-profile cases of wrongdoing — such as the parliamentary expenses scandal — to the recent economic and financial crisis.

Looming behind is the widening chasm between booming multicultural London (expected to back EU membership) and the more Eurosceptic rest of England. “Much of the establishment has no idea what working-class people outside London think,” says Charles Grant, director of the Centre of European Reform, a supporter of the Remain campaign.

In return, Mr Grant says: “Our parliamentary class is treated with contempt, so when the establishment says ‘vote for this, we know what is good for you’ that has little effect. And the same is true for the City of London. The financial services industry is pretty unpopular.”

Indeed, Leave campaigners argue that interventions from “experts” do more to help than to hinder their cause. Tom Banks, the Vote Leave regional director for Yorkshire, says his campaign office saw a spike in interest and support after Mr Obama’s speech against Brexit and the publication of Brexit-critical reports from the Treasury and the IMF. “All these reports and doomsday predictions are only going to make people believe politicians even less,” he argues.

Back in Bracknell, Ms Potts and the other Brexit campaigners are packing up after a few hours of spirited campaigning. The response, they agree, has been overwhelmingly positive, as befits a town that was identified by the YouGov polling group as the third-most-Eurosceptic constituency in Britain.

“Normally people try to avoid these stands, but with the Brexit campaign people actually approach us and ask for leaflets,” says Mr Bellhouse.

What draws the people he talks to is a potent mix of issues — migration, sovereignty, identity — but also the chance to deliver a slap in the face of an increasingly disliked political and economic elite. The establishment, whether in London or Brussels, stands accused of no longer listening. But it will listen — anxiously, fretfully — on June 23.

Comments