China: With friends like these

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

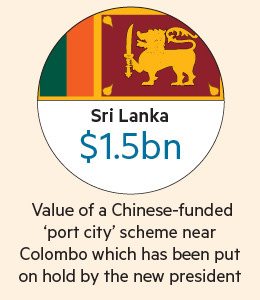

In global terms, the defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka’s presidential elections in January ranked as a mere political tremor. But for China’s policy of financial diplomacy — a key strand in Beijing’s strategy to win friends and commercial advantage around the world — the loss has been convulsive enough to rearrange the region’s diplomatic furniture.

Sri Lanka’s new leader, Maithripala Sirisena, has not hid his antipathy toward China. In a veiled reference to Chinese policy-backed loans worth several billion dollars, Mr Sirisena blamed “foreigners” during his election campaign for stealing his country.

“This robbery is taking place before everybody and in broad daylight . . . if this trend continues for another six years our country would become a colony and we would become slaves,” he said in his manifesto.

Since his victory, Colombo has informed Beijing that it is reviewing the terms of its loans. It has also suspended work on a $1.5bn port project being built by the state-owned China Communications Construction Company. And while Sri Lanka says it hopes to keep warm ties with Beijing, last week Mr Sirisena also stepped up his courtship of China’s main regional competitor, by welcoming Narendra Modi on the first visit by an Indian premier for 28 years.

The reversal is not an isolated setback for China’s “cheque book” foreign policy but the latest in a string of upsets that have punctuated Beijing’s attempts to secure resources, markets and strategic alliances in developing countries with policy-driven loan deals.

Risky business

Ukraine is heavily in arrears in its Chinese lending, while Zimbabwe has failed to repay a much smaller amount. Other recipients of Chinese policy-driven finance — such as Venezuela, Ecuador and Argentina — are suffering varying degrees of economic distress, casting doubt on their ability to repay. “China is taking on too much risk in its lending to regimes that are unstable in Africa, Latin America and even in some Asian countries,” says Yu Yongding, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences think-tank. “Many Chinese institutions thought that as long as they made deals with the governments, the deals are done. But political reality is much more complicated.”

For China, there is much more than money at stake. Beijing has used its status as the world’s biggest provider of development finance to burnish claims of leadership in the developing world, deploying funds from its $3.8tn in foreign currency reserves to boost relations with countries that sometimes have an anti-US agenda. But this model now looks compromised, analysts say. Bilateral deals stitched together in secret with countries afflicted with poor credit ratings, insecure governments and ailing resource sectors have shown a propensity to unravel.

The change in China’s financial diplomacy model has implications for the wider world. There are signs that Beijing is growing less tolerant of the more egregious risks, a trend that could deprive some of the world’s most fragile economies of crucial lines of credit. Beijing also appears intent on spreading its risk, embracing a more institutional and multilateral approach — as demonstrated by its plans for an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank. In addition, there are tensions within Beijing over how far these Chinese-led institutions should be purely profit-driven and to what extent they should pursue the country’s political and strategic agendas, analysts say.

What are the credit risks and the political risks that China faces?

Even minor changes in the way that China deploys development finance could have a significant impact, given the scale of its operations and the speed of its growth since the 2008 crisis.

The opacity of its disbursements and the lack of comprehensive official data make it difficult to calculate how much Chinese state institutions actually lend. Fred Hochberg, chairman of the US’s Export-Import Bank, says Chinese state institutions have pledged a whopping $670bn in recent years, while others point to more modest numbers.

Kevin Gallagher, associate professor at Boston University’s Frederick Pardee School of Global Studies, and Margaret Myers, programme director at the Inter-American Dialogue, a think-tank, maintain a database showing that Chinese government-related lending to Latin America has totalled $119bn since 2005, up $22bn in 2014 alone. Deborah Brautigam, professor at Johns Hopkins University, curates a database on China-Africa lending that shows disbursements of $52.8bn between 2000 and 2011.

Mr Gallagher believes the end of the commodity supercycle and the low price of oil will expose several of the economies that China has supported most vigorously. “Somewhere in Latin America or Africa, one of these countries is going to default on their Chinese loans,” predicts Mr Gallagher.

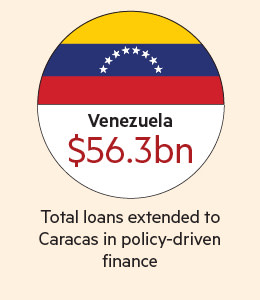

Venezuela, in particular, is a source of alarm. China has lent a total of $56.3bn in 16 loan tranches to the country, according to Inter-American Dialogue data. The country’s economic meltdown has prompted bond investors to price in a 90 per cent likelihood of default in the next five years. Beijing is perturbed. It refused the entreaties of Nicolás Maduro, the president, who travelled to China seeking a bailout earlier this year.

The debt deal was initially struck by “a friend of the Chinese people”, the late Hugo Chávez, Mr Maduro’s predecessor. Checks and balances were skirted, with the debt bypassing authorisation by parliament on the grounds that because it was to be repaid in oil — not in dollars — it could not be classified as “debt”.

This has meant, according to Ricardo Hausmann, director of the Center for International Development at Harvard University, that the money was never accounted for in the national budget, thus escaping national oil revenue-sharing rules. However, when PDVSA, the national oil company, was unable to meet its debt-for-oil repayment schedules, it was forced to borrow from the central bank, contributing to the hard currency shortage that is fuelling inflation and curtailing imports of food.

China’s cooling toward Venezuela stems not only from concern over Caracas’s economic management. The once-voracious appetite for oil and base metals that drew Beijing and Latin America into a clinch has now dissipated as the Chinese economy slows. “While countries such as Venezuela have previously enjoyed something of a special relationship with China, the Chinese government does not appear to have the appetite to write a blank cheque to bail them out now that lower commodity prices have exposed strains in their balance of payments,” says David Rees, an analyst at Capital Economics.

In the case of Ukraine too, Beijing has cooled its early ardour. Viktor Yanukovich, the kleptocratic former president of Ukraine, was received by Xi Jinping, China’s president, with a special warmth in 2013 to affirm a bilateral “strategic partnership”. But since Mr Yanukovich’s overthrow and China’s pivot toward Russia, Beijing’s dealings with Kiev have descended into wrangles over some $6.6bn in debt arrears.

Such setbacks, analysts say, are likely to convince China to route more finance through the new multilateral institutions it is set to lead. The key motivation behind its lending programme also appears to be in flux; over the last decade the main purpose was to seek access to resources but this is now giving way to an imperative to open up overseas markets for China’s engineering giants.

“Putting [China’s foreign exchange reserves] into US Treasuries isn’t getting much of a return, so lending them out in infrastructure projects is a win-win situation that generates business for large companies that are facing overcapacity at home,” says Prof Brautigam.

Grand projects

The scale of the infrastructure ambitions may exceed anything yet seen in terms of resource-related commitments. A case in point is the Twin Ocean Railroad Connection, a planned 5,000km railway to run from cities on Peru’s Pacific coast through the Andes mountain range to Brazil’s Atlantic coast. There is no estimate as yet on the cost of the project but Mr Xi has signed memoranda of understanding — indicating its importance to Beijing.

Similarly, China’s “New Silk Road” initiatives — which envisage billions of dollars in investment to build transport infrastructure across Eurasia, the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean — is animated at least partly by helping state-owned producers of cement, steel, ships and heavy equipment export their overcapacity, says Tom Miller of Gavekal Dragonomics, a research unit in Beijing.

The nature of such infrastructure megaprojects — to be built over a long period and spanning national territories — compels China to spread the risk. “Due to China’s overcapacity, it needs to lend to facilitate its exports by, for example, providing credit to some countries so that China can help them to build high-speed railways,” says Prof Yu. “To minimise loss and risk, China needs co-operation with other countries in risky investments.”

It is against this background that Beijing is establishing a new generation of institutions to rival the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and other entities that have dominated development finance under the “Washington consensus” since the second world war.

A decision by the UK and other European powers to join negotiations to become one of the founder members of the AIIB — in spite of strong opposition from Washington — demonstrates the pull of China’s planned infrastructure-related lending. What is not clear is what sort of rules may govern the lending protocols of the AIIB, the NDC — which embraces Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa as members — and the $40bn “Silk Road Fund”. It is in this domain that China — as well as its partners in these new multilateral institutions — may struggle to reconcile competing agendas.

Yun Sun, an expert on Chinese foreign policy at the Stimson Center in Washington, says there has been pressure to use the AIIB’s loans to “advance China’s economic agenda, especially the export of Chinese products and services”. Chinese foreign policy strategists, meanwhile, have argued that the bank “should support China’s strategic interests, with a result that countries disrespectful of China should receive less favourable consideration”, she adds.

Such ideas present a challenge not only for China, but also for the countries that join the multilateral lenders that it leads. Beijing’s shifting strategic interests are often at odds with those of its neighbours and western powers, while the aim of promoting Chinese exports may not appeal to all partners. Thus, the mutual acquiescence that underlies the current US-led system in international development finance may prove elusive under Chinese management. The “Washington consensus” could become the “Beijing dilemma”.

***

Credit risks

A total of $56.3bn in Chinese credit has been extended to Venezuela, accounting for the lion’s share of a total stock of $119bn in finance from China to Latin America since 2005, according to figures from Inter-American Dialogue, a think-tank. Credit risks are soaring, with the economy set to shrink by as much as 7 per cent this year. The slump in crude prices is clobbering Caracas’s ability to finance its debt. The markets are pricing in about a 90 per cent probability that Venezuela will default on its debt over the next five years. Chinese lending may, in effect, be senior to that of international bond holders, secured as it is against 450,000 barrels a day of oil.

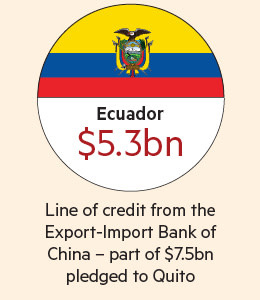

China extended a $7.5bn line of credit to Ecuador earlier this year, with a significant $5.3bn of it coming from the Export-Import Bank of China. But like Venezuela, the country faces severe strains in its balance of payments that have been exacerbated by oil prices at $60 a barrel.Capital Economics estimates that the $7.5bn will plug only about 75 per cent of the expected hole in Ecuador’s balance of payments this year, while finding fresh sources of finance may be difficult given the double-digit yields on sovereign bonds and the country’s poor relationship with institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

China has provided Zimbabwe with about $1bn in credit lines but is growing cooler toward the African nation. Sinosure, a leading Chinese insurance company, has refused to guarantee loans from Chinese state banks to Zimbabwean companies because of Harare’s failure to repay arrears worth more than $60m, according to the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper. President Robert Mugabe was hoping to secure a $10bn financial bailout package with an initial tranche of $4bn during a visit to Beijing last year. Instead, he obtained a $2bn deal for the future construction of a coal mine, power station and dam secured against future Zimbabwean mining tax revenues.

Chinese lending to Argentina has totalled $19bn since 2005 but since the country defaulted on its foreign debt in July 2014, for the second time in 13 years, it has had increased difficulty accessing international capital markets. Thus, the government of Cristina Fernández, who caused a storm during a visit to Beijing in February with a tweet that transposed the letters “l” and “r” in an apparent satire on Chinese speech, is relying on Beijing to keep its economy afloat, drawing down $3bn from an $11bn currency swap facility to boost its foreign exchange reserves. Nevertheless, the low oil price is leading to an improvement in Argentina’s balance of payments position.

Political risks

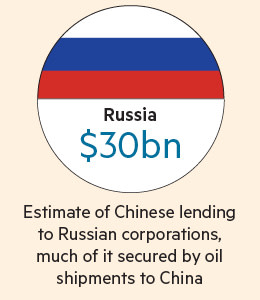

Russia’s financial arrangements with China are shrouded in mystery which is reinforced by western sanctions imposed on Moscow since the Ukraine crisis began. However, several analysts put Chinese state-backed lending to Russian corporations at well over $30bn, much of it secured by oil shipments to China. Even with the oil-price driven slump in Russia’s economy, a default on its debt to China is seen as unlikely, given Moscow’s strong foreign reserves

and oil output. Indeed, the key risk associated with Russia is less financial than diplomatic: that Beijing’s warming relationship with Moscow could alienate the US and other western powers.

Ukraine enjoyed a “strategic partnership” with China under its ousted former president Viktor Yanukovich. Beijing had extended some $10bn in credit lines to Ukraine, followed by another $8bn in investment and government-related lending pledges in late 2013, according to Mr Yanukovich and other former officials.The crisis in Ukraine appears to have derailed the proposed $8bn in investments and credits, while Kiev is heavily in arrears on a $3bn loan backed by promised grain exports to China, according to reports. A further $3.6bn Chinese loan made in 2012 to pay for the gasification of coal by Naftogaz is under renegotiation, the company says.

Sri Lanka’s new president, Maithripala Sirisena, informed Beijing last month that it will review and potentially renegotiate a series of Chinese-funded infrastructure projects, most prominently a $1.5bn “port city” commercial development being built on reclaimed land off Colombo. The new government has also criticised the lax transparency and high costs on Chinese-backed projects developed under former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, who developed close ties with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. These include a second international airport close to Mr Rajapaksa’s home town, which has received little use since opening in 2013, and two new port developments.

The switch from a military junta to a nominally civilian government in Myanmar in 2011 led to the suspension of work on the $3.6bn Myitsone Dam, a project developed by the state-owned China Power Investment Corporation and financed from sources within China. The dam became a focus of public anger over what was seen as Beijing’s growing role in the country. Negotiations over compensation for some of the investment made by the Chinese side are continuing. A $20bn railway from the Chinese city of Ruili across Myanmar to the Bay of Bengal has been put on hold, voiding a 2011 agreement that envisaged a 50-year build-operate-transfer agreement.

Additional reporting by Geoff Dyer and James Crabtree

Comments