China data point to sharper slowdown

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

China’s economy slowed at its sharpest rate in the first two months of the year since the global financial crisis, heightening fears that this deceleration will undermine global growth.

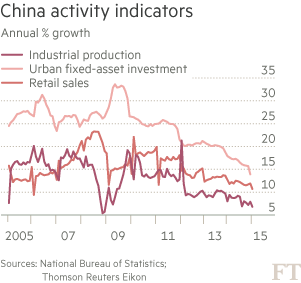

Chinese industrial production, regarded as a good proxy for broader economic growth, expanded 6.8 per cent in January and February from a year earlier. Excluding the financial crisis, it was the slowest reading since records started in 1995, Goldman Sachs said.

Fixed asset investment and retail sales also slowed significantly, data showed on Wednesday.

“Today’s disappointing data release highlights just how quickly domestic demand is deteriorating as the ongoing property downturn continues to spread its negative impact through the economy,” said Wang Tao, UBS chief China economist.

Weakening Chinese demand has been one of the main causes of falling global commodity prices and weaker emerging markets. An extended slowdown in the economy could further sharpen the divergence developing between the US, whose prospects have been brightening, and other important global economies.

Expectations that the US Federal Reserve will soon raise rates is sending the dollar rocketing higher, while central banks in the eurozone, China and many emerging markets are all easing to fight falling inflation and shore up growth.

China expanded at the slowest pace since 1990 last year, contrasting with the decades of double-digit growth since the late 1970s. The International Monetary Fund has already cut its gross domestic product estimate to 6.8 per cent this year and 6.5 per cent in 2016, the first time the IMF forecast lower growth in China than in India for decades.

Fixed asset investment, key in an economy where investment contributes more to growth than almost any other in history, expanded 13.9 per cent in the first two months from a year earlier, down from an annual expansion of 15.7 per cent last year.

Retail sales, one measure of how successful China has been at shifting to a more consumption-based growth model, also slowed in the first two months, expanding 10.7 per cent compared with 11.9 per cent growth in December.

The broad slowdown is being led by a serious decline in China’s previously overheated real estate sector, where prices and sales have fallen since the start of last year.

In a sign of further pain to come, housing sales in the first two months of the year fell 16.3 per cent in terms of floor space from a year earlier, after falling 7.6 per cent in December.

China’s housing market has only existed since the late 1990s when the government privatised and commercialised housing that was previously assigned to people by the government or their “work unit”.

The latest figures confirm the worst fall in the market since at least the financial crisis, following more than a decade of frantic building that has created massive oversupply and left countless half-built and half-empty apartment complexes across the country.

The full impact of the housing slump is yet to be felt.

Property investment increased more than 10 per cent last year to Rmb9.5tn ($1.5tn) while sales fell roughly 8 per cent in terms of floor area.

This has exacerbated oversupply and thus the prospect of much slower overall economic growth once investment follows sales down.

“Economic momentum appears markedly weaker than suggested by the recent recovery in export growth and Purchasing Managers’ index readings,“ said Julian Evans-Pritchard, China economist at Capital Economics. “As such, a further slowdown in GDP growth in this quarter now looks likely.”

The growth in fixed asset investment in the first two months was the weakest in China since December 2000, when the country’s banking system was technically bankrupt following a massive build-up of bad loans in the 1990s.

The latest industrial production figures are the worst since December 2008, in the immediate aftermath of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy and a subsequent collapse in Chinese exports.

China is also struggling with a huge and growing debt load and the threat of deflation.

At 282 per cent of GDP by the middle of last year, according to estimates from McKinsey, China’s overall debt load is higher than that of the US or Germany.

The economy expanded 7.4 per cent last year, the slowest pace in almost a quarter of a century and the government has lowered its growth target this year to “around 7 per cent” from last year’s “around 7.5 per cent”.

Still, many economists believe the slowdown in the property market will make it difficult for Beijing to achieve that lower goal.

“The extremely weak activity data at the beginning of the year suggest that China needs to engage into more aggressive policy easing,” Li-Gang Liu, chief greater China economist at ANZ, wrote in a note, adding that China’s first-quarter growth could miss 7 per cent.

Comments