Question & Answer: China’s share trading suspensions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If corporate management, like diplomacy, can be said to be war by other means, China’s two most famous military strategists would probably approve of the moves by more than 1,400 Shanghai and Shenzhen-listed companies to suspend trading in their shares. Both Sun Tzu, author of the Art of War, and the father of China’s Communist revolution, Mao Zedong, knew the folly of an army venturing on to the battlefield when conditions were not in its favour.

How extensive are the suspensions?

On Wednesday morning, hundreds more companies said they would suspend trading, bringing the total to 1,476, more than half of China’s 2,808 listed companies.

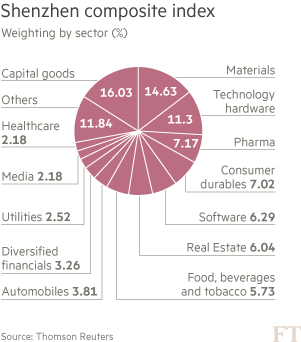

Most are listed on the Shenzhen stock exchange’s ChiNext board, the preferred destination for technology companies and China’s answer to the Nasdaq. The ChiNext has risen further, and fallen faster, than any of its domestic peers.

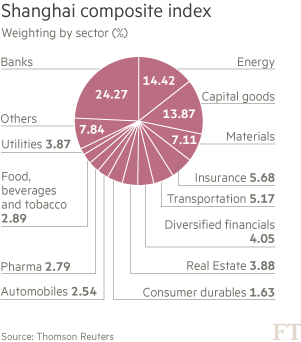

This was reflected in Tuesday’s 5.3 per cent fall in the broader Shenzhen Composite index, compared to the Shanghai Composite index’s 1.3 per cent decline.

Why are they doing this?

Most of the companies have cited “significant matters”, a phrase that would normally hint at an impending merger, acquisition or restructuring.

It is unlikely, however, that China is on the cusp of an M&A boom, especially in the context of a market that has shed more than 30 per cent of its value in about three weeks.

Some analysts believe the suspensions are instead related to one of the scariest “known unknowns” surrounding the market meltdown — just how many controlling shareholders have pledged their shares as collateral for bank loans.

Those who have pledged shares could be required to liquidate them when their value falls a certain amount, potentially triggering another major sell-off.

It is one of the biggest potential “transmission mechanisms” between China’s stock markets and the wider economy.

How long can these suspensions last and why aren’t all companies seeking shelter from the storm?

The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges have complicated rules specifying different suspension periods, for reasons ranging from major asset restructurings to whether a company is concerned that price-sensitive information may leak. While the rules require various levels of disclosure when a company seeks to extend its suspension, they can effectively halt trading for weeks or months at a time.

The more companies that suspend their shares, the worse China’s stock markets look. Most companies that have done so are not particularly well known, and state-controlled firms are now buying blue-chip stocks in an effort to support the Shanghai and Shenzhen Composite indices. If blue-chips were to stop trading, the government might as well just close the markets outright.

Can avoiding a market meltdown and wider banking crisis really be as simple as that?

Hardly. The latest suspension applications may be rejected by the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. They and their regulator, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), know that this looks terrible and represents a huge reputational risk.

Moreover, the Chinese government has long prided itself for acting “responsibly” in times of crisis. Most notably, it did not devalue the renminbi when its neighbours’ currencies plummeted during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, even though this rendered China-based exporters less competitive. Ten years later, Beijing took extraordinary measures to boost domestic demand during the global financial crisis, providing a crucial fillip for the global economy.

Mass suspensions, however, are essentially a more discrete form of market closure — one of the worst policy responses a government can take. The Indonesian government infamously closed stock markets for a few days during the depths of the global financial crisis.

So what does this mean for minority shareholders, especially the small “mom and pop” retail community, and foreign investors?

Many retail investors may, in fact, welcome the suspensions, which at least postpone any reckoning they may have to face. Even when a company’s trading suspension is lifted, “circuit breakers” restrict any one stock’s daily fall to 10 per cent, so it would take a while for them to catch up with the broader market collapse.

For foreign investors, the suspensions raise significant concerns. Over recent years, the CSRC has rapidly expanded its quotas for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors as part of Beijing’s broader strategic aim of internationalising the renminbi. Institutional investors, however, take a dim view of such gamesmanship.

Last month, the MSCI decided to delay inclusion of Shanghai and Shenzhen-traded shares in its global emerging market index — probably until May 2017 — meaning that China Inc’s representation remains restricted to Hong Kong-listed H shares and red chips, the mainland China companies incorporated outside mainland China and listed in Hong Kong.

The current controversy over China’s mass trading suspensions would appear to validate that decision.

Additional reporting by Wan Li

Comments