Indians sound alarm over ‘Orwellian’ data collection system

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

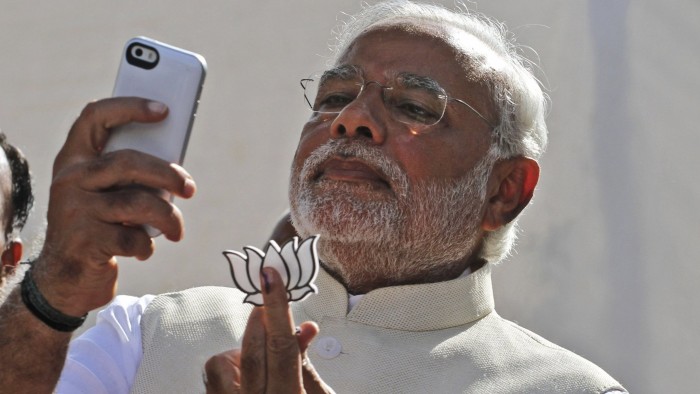

India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, is one of the world’s shrewdest political leaders when it comes to using social media to mobilise his supporters and forge the sense of a personal connection. His NaMo app — launched three years ago, repeatedly upgraded, and relentlessly promoted — disseminates his personal ruminations along with cheery infographics showing India flourishing under his leadership. The app also relies on gaming techniques to engage users, encouraging them to “contribute and earn badges” by completing “to-do tasks”.

Downloaded more than 5m times and pre-installed on around 40m low-cost Reliance Jio phones, the app has helped Mr Modi shape India’s political narrative. His Bharatiya Janata Party also has a hyper-active social media cell, which is frequently accused of trolling government critics, while his cabinet ministers act as a virtual Twitter chorus, spreading carefully curated political messages.

Yet, as Mr Modi gears up to fight for a second five-year-term in national elections next year, he appears to be seeking new weapons for his social media arsenal. The government recently put out a tender for developing a “real time new media command room”, which would operate 24/7 to “collect all digital media chatter” and “analyse trends” from social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and scrape data from news websites, blogs, forums and emails.

Staffed initially by at least 20 social media analytics professionals, the hub will “gauge the sentiments among netizens” and advise on “how nationalistic feelings could be inculcated into the masses”.

It would also map “people who are creating a buzz across various topics”, categorise social media conversations as “positive, negative or neutral” to the government’s perspective, and store content about people and their conversations in a vast, searchable database. The hub should improve “the perception management” of India, and advise how “the media blitzkrieg of India’s adversaries be replied/neutralised,” the tender says.

The government has offered little rationale for the operation, for which $6m has been initially budgeted. But Apar Gupta, co-founder of India’s non-profit Internet Freedom Foundation, says such an Orwellian system would violate Indians’ constitutional rights to free expression, and privacy.

“It’s a mass surveillance system and it also has capacity for disinformation and propaganda,” he says. “It’s exactly like the two-way screen in 1984.” Mr Gupta believes the initiative is inspired by China, which closely monitors its citizens’ online activity. But in India, Mr Modi’s government could face a legal battle, as critics try to stop the project in its tracks.

On Friday, the Supreme Court will hear a legal challenge filed by an investment banker turned opposition politician, Mahua Moitra, who calls the hub a “a brazen attempt” to spy on Indians, profile people who are critical of the government and “cut them to size in order to compel them to toe the government’s line”. Concerns have been already echoed by Supreme Court judges, who this month expressed worries that the project was a step towards turning a constitutional democracy into a “surveillance state”.

Mr Modi has been accused of over-reach in data collection before. In March, Rahul Gandhi, leader of the opposition Congress party, claimed that the NaMo app was allowing Mr Modi’s campaign team to access the entire contents of users’ phones, including contact lists and photos.

The premier’s team dismissed the furore, saying the app’s data collection was little different than the kind used by Facebook and other commercial social media platforms for targeted marketing of consumer products.

Indians are already engaged in a vigorous debate about their online privacy, and the lack of a modern data projection law. Many are challenging the drive to require citizens to use the government’s biometric identification card, Aadhaar, for a wide range of consumer activities, including buying mobile phone sim cards, opening bank accounts, or even purchasing domestic flight tickets. The government’s new quest to track online expressions of political and social opinions — and the activity of social media influencers — will only fan fears about its ultimate intent.

Letter in response to this column:

Nothing surreptitious about the NaMo app / From Bhaskar Mukherjee, Windsor, Berks, UK

Comments