Wellness schemes benefit employers as well as staff

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Every working day after 7pm and throughout the weekend, the staff at Health Innovation Network are encouraged to disengage with email. If anyone is determined to write messages out of hours, they are urged to save them in draft and hold off sending them until the next weekday morning.

“We want to make sure people switch off, so we have a curfew for recharging. You need to be with your family and have a digital detox,” says Tara Donnelly, the chief executive. The move is one of several initiatives she has overseen to help ensure her organisation promotes healthier living for its staff as well as clients.

Her approach reflects that of a growing number of top executives from employers of all sizes in the public, private and non-profit sectors alike. They are exploring ways to promote better workplaces in order to recruit and retain staff, support their health and, in the process, boost productivity.

Health Innovation Network, a unit of the UK’s National Health Service that employs 70 staff, including nurses and paramedics, has a particular justification. It specialises in supporting innovative but proven approaches to effective healthcare, such as doctors prescribing gym sessions rather than just drugs to tackle pain, depression or the development of chronic illnesses.

Help offered to staff at Health Innovation Network range from free yoga and mindfulness classes to desks that can be used standing up, mental health awareness training and the provision of showers to encourage physical exercise such as cycling to work. Employees can join the book club or running club, and are encouraged to leave their desks to chat with colleagues in the office garden. “It feels very appropriate that we do everything that helps people live a healthy lifestyle ourselves,” says Donnelly. “Our only asset is our staff. We need to look after them and keep them. It makes sense morally and it makes business sense.”

There has been similar thinking outside the healthcare sector, too. Skyscanner, an internet travel search site, offers subsidised gym membership, weekly massages, treadmill desks and access to a mindfulness app.

It recently launched an extended leave programme for longer-serving employees, a chance for expatriates to spend three weeks back in their home country and for any staff member to work for up to a month in another country where the company has offices.

“We believe it’s our duty to provide a workplace in which employees can thrive,” says Julia Clement, talent director. “Some of our initiatives have been driven by employee requests and suggestions, some are natural parts of our office design, and others are driven by our culture and values as a business.”

The increased awareness among employers has been tracked in Britain’s Healthiest Workplace survey, devised by VitalityHealth, the health insurer, and produced in association with Rand Europe, the research institute, the Financial Times, the University of Cambridge and Mercer, the human resource consultants. The survey seeks to identify the extent and impact of such interventions and this year generated responses from nearly 32,000 employees in 167 organisations.

“There has been a growth in interest,” says Shaun Subel, director of strategy at VitalityHealth, which has built a significant business model in several countries by offering health insurance and providing incentives to encourage the take-up of activities to improve wellbeing.

Dame Sally Davies, the UK government’s chief medical officer, is one leading figure who has been trying to raise awareness of the benefits of workplace wellbeing programmes. Public Health England, which advises and supports national health services, has developed tool kits and is analysing online health apps to encourage best practice.

In the private sector, associations such as Business in the Community, a business-led charity that promotes ethical and sustainable behaviour, and the British Safety Council have become more active, issuing guidelines and holding events to spread the message. Companies such as GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceuticals group, have started to develop benchmarks to try to assess the impact over time of wellbeing programmes they offer.

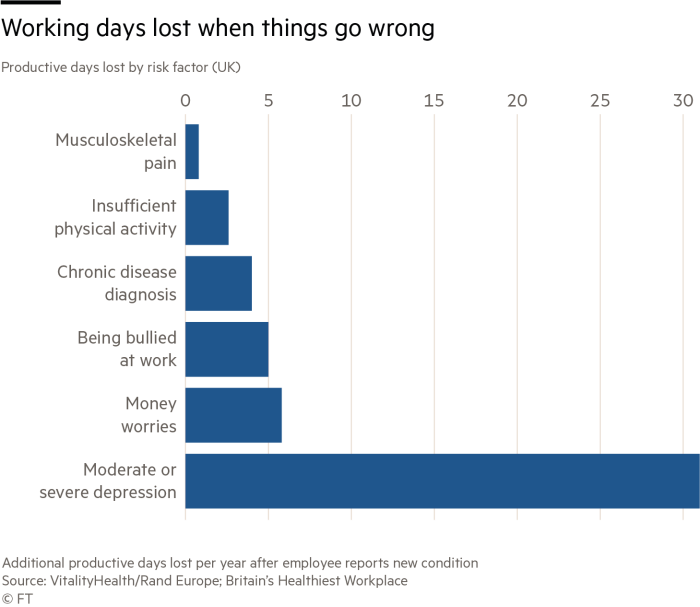

There is little question that an even greater focus on wellness is required. A sobering fact to emerge from Britain’s Healthiest Workplace is that over the past four years, the state of the national workforce has been deteriorating. The average number of annual working days per staff member lost to absenteeism or presenteeism — when employees come to work but are not productive — has risen from 23 to 30.

That mirrors a rise in unhealthy lifestyles. While the proportion of people smoking and reporting excessive alcohol consumption and insufficient physical activity has dropped slightly since 2014, the number not eating healthy diets has jumped from 52 per cent to 62 per cent. Equally, the number of those getting less than seven hours’ sleep a night has risen from 26 per cent to nearly 30 per cent.

Mental health problems can lower productivity significantly, and even relatively minor concerns, such as employees feeling they lack control over their work, or that their manager does not support them, can have a negative impact. The proportion of respondents who reported suffering from moderate or severe depression has jumped from below 4 per cent to nearly 6 per cent this year. Two-thirds of employees said they have at least some financial concerns — which the survey also identifies as a significant cause of stress.

Furthermore, these patterns are likely to be underestimates, given the data are based only on employers and employees who voluntarily complete the questionnaires and are typically already convinced of the value of workplace health interventions. Many of the least healthy staff and least enlightened employers simply do not participate.

The responses suggest that wellness programmes have a positive impact. Among initiatives to promote physical wellbeing, the survey shows that staff value on-site gyms, fitness breaks and classes, running clubs and support for walking or cycling to work. For mental health support, respondents said massage or relaxation classes, cognitive behavioural therapy and training in time management would help them most.

But there is no simple menu from which employers can pick to transform their workforce. The first challenge is the difficulty in gathering rigorous data on how effective any particular intervention might be in comparison with another. When companies do try to improve their employees’ health, they tend to employ several approaches simultaneously, rather than just one. In addition, the interventions that staff and their managers might value the most do not appear to correlate closely with the actual impact.

“There is an absence of evidence,” says Theresa Marteau, director of the behaviour and health research unit at the University of Cambridge. She is researching the impact of calorie labelling, portion sizes and the prominence given to healthier food as a “nudge” to better eating at workplace canteens.

A second challenge is uptake. Even among participants in Britain’s Healthiest Workplace, while 62 per cent of employers offered wellness programmes, only 28 per cent of employees used them. Although physical fitness facilities prove popular, mental health provisions — which the BHW research suggests would have the greatest impact because of mental health’s disproportionate effect on productivity — are less so.

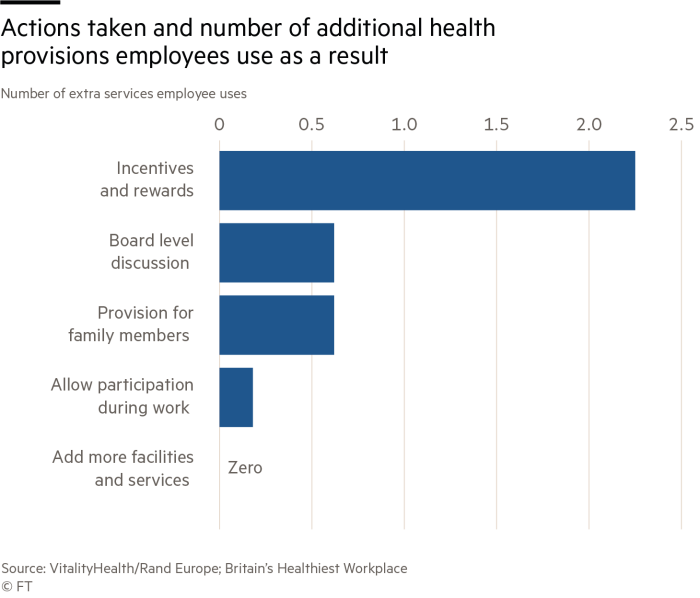

Subel at VitalityHealth warns that simply adding additional wellness programmes will not necessarily provide a corresponding benefit. “There’s not a linear link,” he says. Employees who are already committed will often be responsive when offered more options, but companies can achieve far bigger returns if they can accomplish the harder task of getting those who are unengaged to participate.

Subel says incentives for employees — rewards of some kind for choosing salads rather than chips, for example — are fundamental to achieving the best results. Engagement of senior executives in the initiatives is also an indicator for success.

Peter Simpson, chief executive of UK utility company Anglian Water, agrees. “Wellbeing is written into our business plan and our annual reporting,” he says. “It has become a strategic boardroom issue. Employees should be on the balance sheet in the same way as you account for cash. People think it’s a bolt-on, but we say this is part of our business strategy.” He recalls a two-day board meeting at which a full day focused on employee development and wellbeing.

He has changed the type of food in the canteen, provided adjustable desks and personal “resilience training” for managers to teach them how to bounce back from adverse events.

He has also promoted health checks for staff and encouraged “walking meetings” rather than seated ones around a table. He calculates the result has been an eight-fold return on investment, measured through factors such as a reduction in absenteeism, improved customer satisfaction with staff, and falling illness claims, which have halted inflation in private healthcare premiums.

A final difficulty with expanding wellness programmes is finding the resources to pay for them. Some policymakers have called for tax write-offs or business rate deductions for those who provide support.

Authorities in the UK’s West Midlands have decided to pursue another route, and are even exploring the idea of “early adopter” grants for employers willing to test the impact of different programmes by the start of next year, according to Sean Russell, director of implementation for West Midlands Mental Health Commission. Russell says the focus will be on two of the biggest burdens: workplace stress and musculoskeletal conditions. “In lots of organisations, people won’t talk about mental health but they will talk about a bad back,” he says.

As the UK economy shows signs of slowing down, wellbeing initiatives that could boost productivity in the long run might start to become more widespread.

Comments