Best of FT Money 2021: How to protect your investment portfolio against inflation

Simply sign up to the Investments myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On leaving his job as chief economist of the Bank of England this week Andy Haldane delivered a disconcerting critique of his fellow central bank policymakers.

Speaking at the Institute for Government, he warned that people and companies had “a dependency culture around cheap money” and that the threat of a rapid increase in prices was “rising fast”.

His view stands in contrast to mainstream central bank thinking, including at the Bank of England. It nonetheless reflects growing concern about inflation fuelled across global markets by the release of data in June showing that US consumer prices increased by 5 per cent in the year to May.

The rest of the developed world is recovering more sedately from the Covid-induced recession but inflationary pressures are becoming apparent, not least in the UK.

Haldane expects inflation to be 4 per cent, double the BoE’s target, by Christmas. The big question is whether this will herald a return to much higher inflation and even a wage-price spiral of the kind we last saw in the 1970s.

Investors who take that risk seriously must recognise that the era of ultra-low interest rates may be over, in which case fixed-interest bonds, which currently yield next to nothing will prove toxic. As central banks raise rates to address inflation, bond yields will follow and bond prices will fall, inflicting heavy capital losses on investors.

The merits of gold, commodities, property and index-linked securities in a more inflationary environment will need to be carefully weighed. None of these assets provides a perfect inflation hedge but they do offer an element of portfolio protection.

Meanwhile, the relative attractions of growth stocks, including high-flying big tech, and value stocks, often in traditional industries, may need rethinking.

FT Money explores the risks and options for investors in a more dangerous economic landscape where price stability cannot be taken for granted.

The losses of the 1970s

The folk memory of the 1970s has faded to the point where it is worth reiterating just how much damage inflation wrought on investment portfolios in the decades after the second world war. Between July 1945 and May 1979, retail prices rose cumulatively by 632 per cent. Over that time the gilt market saw undated War Loan fall in value in nominal terms by two-thirds, inflicting a capital loss in real terms — adjusting for inflation — of 95 per cent.

War Loan had traditionally been regarded as Britain’s ultimate safe asset, the bedrock of the most risk-averse investors’ portfolios. Yet, at the worst point in the inflationary 1970s, its yield topped 17 per cent.

War Loan no longer exists — the last undated gilts were paid off during George Osborne’s chancellorship. And that astonishingly high yield compares with a yield on today’s longest dated gilts of a little over 1 per cent.

Even a relatively small move back in a 1970s direction would inflict serious capital losses on current investors in fixed-interest gilts.

As for equities, they saw a savage bear market in the mid-1970s, while company profits were hit by the twin scourge of government-imposed price controls and costs spiralling at a faster rate than inflation due to the quadrupling of the oil price and uncontrollable wage increases. Between May 1 1972 and December 13 1974 the FT All-Share index lost 72.9 per cent of its value.

Did commercial property, widely regarded as a good hedge against inflation, provide any relief? Not at all. The market collapsed, inducing the worst banking crisis since the 1930s.

It is most unlikely that there will be a repeat of the extreme surge in the general price level experienced at that time, which saw inflation peak at 26.9 per cent in August 1975 as measured by the retail price index. Trade union bargaining power, a crucial driving force behind the wage-price spiral, was broken by Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s. The reserve army of labour in Asia and other parts of the developing world continues to exert downward pressure, albeit a diminishing one, on wages.

Yet there remain good reasons to question the current central banking conventional wisdom on inflation, as reflected in the BoE’s latest Monetary Policy Report. In essence, this boils down to the belief that the rise in inflation resulting from the current imbalance between burgeoning demand and constrained supply, as economies emerge from the Covid recession, is transitory. Increases in the prices of food, energy and other commodities are likewise partly attributed to non-recurring “base effects” from weak prices in the pandemic, which will shortly fall out of the annual calculation of the consumer price index.

According to this school of thought, rises in business costs caused by a one-off bounceback in demand and temporary supply bottlenecks should not engender longer term inflationary concern. The suggestion is that such cost increases may simply be absorbed in company margins along with a squeeze on wages rather than being foisted on end consumers. Developed world central bankers, including the BoE Monetary Policy Committee, continue to believe that inflation expectations are well anchored.

Despite the intensity of the debate on inflation, the central banks’ confidence that they have things under control is largely shared by market professionals. The gilt-edged market’s expectation of inflation, as reflected in the difference between the yield on nominal gilts and on index-linked gilts of the same maturity, was 3.3 per cent on 30-year paper in mid-June. This was above the BoE’s 2 per cent inflation target, but scarcely points to Armageddon. And this so-called break-even inflation rate has come down a little since the end of May.

That said, there are grounds for thinking that the central banking consensus is dangerously complacent. Historically, changes in regimes of monetary management have been a clear warning signal on inflation. In the early 1970s, president Nixon’s decision to break the dollar’s link with gold opened the door to a more lax monetary approach while in Britain at around the same time the Competition and Credit Control banking reforms unleashed a frantic acceleration in bank lending.

Are food and energy rises a one-off?

Today’s worryingly permissive monetary developments include the central banks’ loss of appetite for pre-emptive action against inflation — witness the US Federal Reserve’s new policy framework, which includes a focus on current as opposed to prospective inflation.

This is accompanied by a move to average inflation targeting whereby it proposes to tolerate above-target inflation for an unspecified period to compensate for years of undershooting. The thrust is less explicit in the UK but the BoE Monetary Policy Committee’s recent pronouncements have a wait-and-see quality that looks anything but pre-emptive.

The other disturbing historical parallel relates to the perception of rises in food and energy costs as one-off events. The Yale economist Stephen Roach witnessed the birth of the 1970s inflation as a Fed insider. He points out that the then Fed chair, the domineering Arthur Burns, insisted that the surge in oil prices after the Opec oil embargo that followed the 1973 Yom Kippur war had nothing to do with monetary policy and should be excluded from the consumer price index.

Burns also argued that rising food prices, which had a 25 per cent weight in the CPI, were traceable to extreme weather. In fact he attributed so much of the rise in prices to volatile “special factors” that just 35 per cent of the CPI was left for Fed staffers to monitor. Only when this rump of the index was rising at a double-digit rate in 1975 did Burns acknowledge that there was an inflation problem, by which time prices were out of control.

The other 1970s policy error Roach highlights is that by allowing real interest rates to go negative the Fed poured fuel on the great inflation.

Today, he points out, the Fed’s funds rate has been running at more than 2.5 percentage points below the inflation rate. That is accompanied by open-ended quantitative easing with some $120bn per month injected into frothy financial markets along with the largest fiscal stimulus since 1945 — all when the post-pandemic boom is absorbing slack capacity at an unprecedented rate. The painful lesson according to Roach: ignore so-called transitory factors at great peril.

The critique applies with equal force to the UK. Haldane, who was alone on the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee in voting against continuing its bond purchasing programme at the current level, suggests that the present momentum in demand may prove persistent rather than one-off, while supply bottlenecks may prove sustained.

There is mounting evidence, he has argued, that pricing power among companies and bargaining power among workers is being bolstered by resurgent demand.

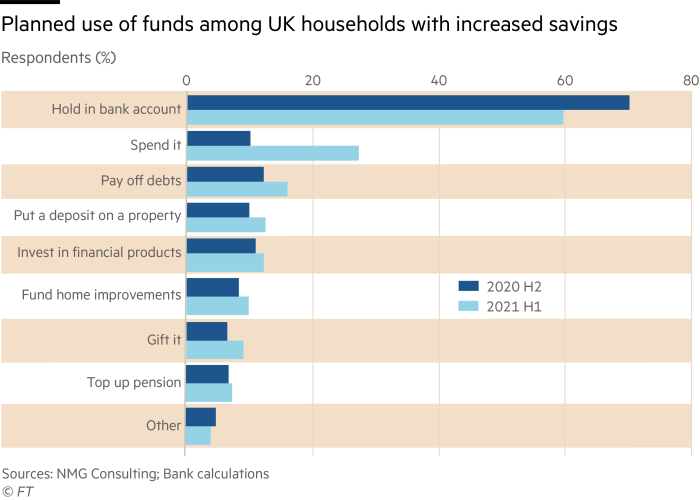

Lending strength to these arguments is the more permissive attitude of policymakers towards deficits and debt since the pandemic. When combined with the build up of cash balances in a household sector that is yearning to go back to high-spending pre-Covid ways, this makes it unlikely that demand will falter any time soon. On the supply side, in addition, the forces of globalisation are in retreat, the British workforce is shrinking and Brexit has curtailed the supply of labour from the EU, leading to staff shortages in many sectors of the economy.

So there is a strong possibility that the long period in which the distribution of corporate profits and wages in national income was biased in favour of capital may now be ending and that wage stagnation may be a thing of the past.

Psychological constraints

Finally, central banks are under an important psychological constraint in confronting resurgent inflation. Raising rates after a protracted period of ultra-loose policy risks destabilising twitchy financial markets and inflicting recession. There is also the risk that in raising borrowing costs of governments that have become heavily indebted since the great financial crisis they would jeopardise their own independence. The temptation to err on the side of inaction is huge.

If investors believe that there is a heightened risk of inflation expectations ceasing to be well anchored, how should they protect their capital and retirement incomes?

This will be difficult, especially since there are flaws in the way pensions funding works in the UK. In defined benefit schemes, where pensions are usually linked to final pay, around £1.6tn of pension liabilities, or 70 per cent of the total, are linked to inflation.

Yet the total index-linked gilt market is only around £800bn. While there are a few index-linked corporate bonds and other assets such as property where rental contracts can be inflation-proofed, the numbers involved are too small to make good this enormous mismatch.

Inflation will also expose shortcomings in liability-driven investing whereby pension funds invest in instruments that are intended to match as closely as possible the quantum and timing of pension payments. While liability matching offers hedges against inflation and interest rate volatility, inflation proofing in defined-benefit schemes is usually capped at three, four or five per cent.

It follows that if inflation exceeds these rates, pensioners will suffer shrinking real income. It is thus vital that pension fund trustees maintain return-seeking components so that there is a source from which to pay discretionary increases to make good the real income losses. Ideally the return-seeking holdings should include assets producing cash flows that are linked or respond robustly to inflation such as property and infrastructure.

For defined contribution or money purchase scheme members, the vital thing is to avoid fixed-interest bonds which currently yield very little and will inflict big capital losses in a more inflationary environment. The longer the duration, the greater the potential for capital loss. Index-linked gilts are also a mixed blessing because they have a negative yield and are thus an expensive and imperfect inflation hedge.

There are better and positive yielding index-linked contracts in infrastructure and property. But few, if any, of the defined contribution platforms run by the big fund management groups offer exposure to infrastructure while the range of choice in property is usually limited. The great majority of scheme members will anyway be in the default section of a lifecycle fund where they may be put, willy-nilly, into both nominal and index linked gilts as their pension pot is supposedly de-risked with the approach of retirement.

In equities the link with inflation is loose. They are nonetheless a better hedge than bonds and good quality equities should, at least in the long run, provide protection against a rising price level. Note, though, that value investing may gain some ground relative to growth investing because with higher interest rates the present value of growth companies’ earnings will be less due to higher discount rates being applied.

More crudely, inflation means that the further into the future money is, the less it is worth. That strengthens the value investors’ case for buying lowly-valued earnings in an inflationary environment.

As for direct investment in property the link with inflation is loose and office and retail property are structurally challenged because of the pandemic and the growth of online shopping.

Residential property is not cheap in today’s frothy investment climate, but with inflation it tends to become even less cheap. This is not a time to be out of the housing market.

That brings us to gold and commodities. There is no direct correlation with inflation and they are volatile. For example, gold was a good hedge in the 1970s until inflation peaked at the end of the decade. But investors in gold in the early 1980s saw it more than halve in value over the next 20 years.

Now the opportunity cost of holding gold or commodities is less than it’s ever been. The yield on most publicly traded securities is paltry. It thus makes sense to have at least a small portfolio stake in gold or commodities, with the additional advantage that they provide genuine diversification.

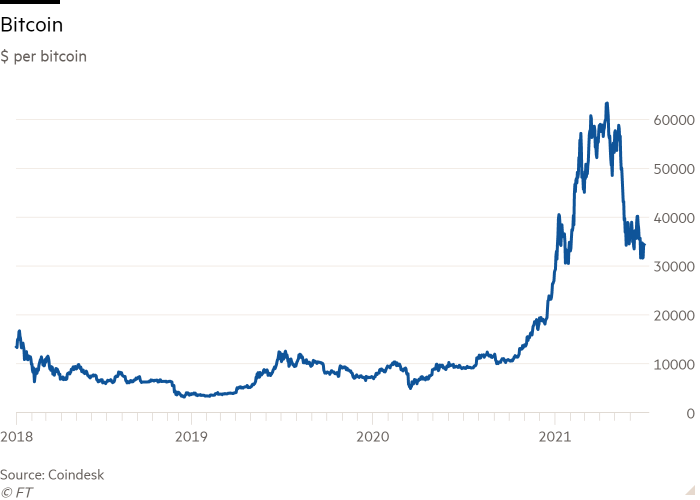

And bitcoin, you might ask? Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, described it as “a combination of a bubble, a Ponzi scheme and an environmental disaster”. That will not deter its passionately ideological devotees. Just bear in mind that faith-based investments can go down — sometimes a very long way down — as well as up. There are safer ways to inflation-proof a portfolio.

Comments