Should you buy an electric car?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Sitting in an electric car on the start line at Silverstone, about to go head to head with the latest Aston Martin, I quietly wonder what on earth I am doing.

While the guttural rumbling from the Aston’s V8 engine seeps into my right ear, the Tesla S I am in (£130,000 on the road) is totally silent. You would not even know it was switched on. But while the Aston has thunder, the Tesla produces lightning — accelerating from 0 to 60mph in under three seconds with a g-force that puts roller coasters to shame.

As the British supercar shrinks in my wing mirror, I can attest that driving an electric car is undoubtedly fun. But for everyday driving, could you really live with a battery-powered vehicle?

It is a question more car buyers are asking. Electric vehicles have graduated from a niche environmental concern to a serious proposition for mainstream motorists, as the technology comes of age and major manufacturers prepare to flood forecourts with battery-driven alternatives.

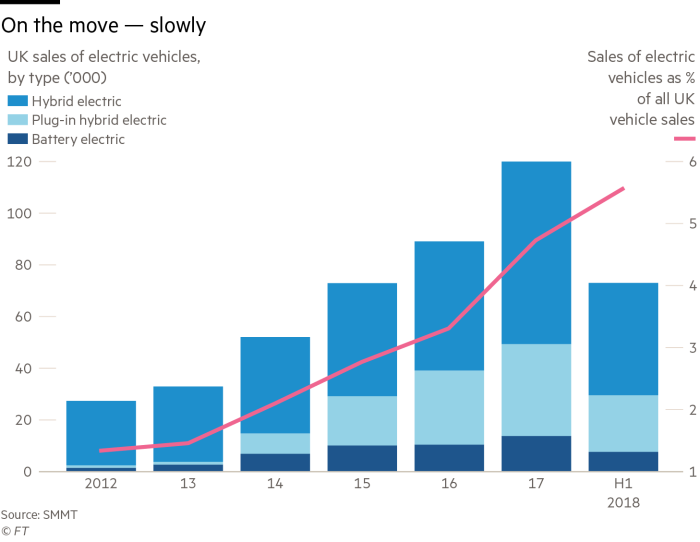

However, sales remain tiny. The majority of buyers are daunted by the high prices of electric cars, plus the limited mileage range, not to mention how — and where — they can recharge their vehicles. About 6 per cent of vehicles sold between January and June this year had a plug, while a mere 0.5 per cent were fully electric, meaning they have no traditional engine whatsoever.

As we enter September, traditionally Britain’s second-biggest month for forecourt sales, here are all the financial points you need to consider before buying an electric car.

What is an electric car?

It may not have been intentional, but the motor industry has made understanding electric cars unnecessarily difficult.

Executives talk about “electrified” vehicles, a vague term that covers a plethora of alternatives from traditional vehicles fitted with 48V batteries, to full-blown electric cars with no petrol tank at all.

Along the spectrum sit mild hybrids, plug-in hybrids, self-recharging hybrids, and other concoctions, each denoting a slightly different iteration of the engine-battery infusion. No wonder car buyers are confused.

Put simply, pure electric cars are powered by a battery, which often sits at the base of the vehicle. Some models, such as the BMW i3 and the new electric London Taxi from LEVC, also offer a small petrol engine that powers the electric motor, turning the wheels to extend the range.

Then there are plug-in hybrids, which use both the battery and a traditional engine to drive the wheels, but have the ability to drive for limited distances using electric power only. The battery has to be plugged in to recharge.

Perhaps the car that most people think of as a hybrid is the Toyota Prius, which is a “self-recharging” hybrid that uses engine power and a battery simultaneously, though is able at low speeds to run on battery over very short distances.

Finally mild hybrids, the closest to today’s cars, with a larger-than-normal car battery used to ease the strain on the engine, allowing bigger vehicles to run with much smaller engines.

Where can I buy one?

A product launch onslaught is coming down the road. Close to 20 pure electric vehicles will be released in the next two years, with dozens more hybrid alternatives.

“So far they have been popular among first-generation early adaptors, but, really, among the general public, they just haven’t taken off yet,” says Erin Baker, editorial director at Auto Trader, the online search website.

“But by the middle of next year, there will just be such an explosion of what’s on the market to choose from which will really widen consumer choice and, hopefully, bring the price down.”

Yet walk into a dealership today and you are likely to be greeted by a long waiting list. The Nissan Leaf and the Hyundai Kona, two leading mass market electric cars, each have six month waiting lists, while the Jaguar I-Pace — the first electric car from an established premium nameplate — will see its first deliveries in October. Dealers say an order placed today is likely to arrive in February.

Meanwhile, aspiring electric motorists are likely to be steered towards petrol models by salespeople. For various reasons, most brands deliberately exclude electric options from their retailers’ bonus schemes — so advising a customer to buy an electric car instead of a petrol one could mean a dealer is less likely to hit that month’s bonus target.

“One or two brands have [sales of electric cars] in the target, but on balance most of them have it outside the target,” says the boss of one dealership company with multiple brands.

However, there are pockets of activity across the UK. A year ago, charging point company Chargemaster opened an electric vehicle education centre inside a shopping centre in Milton Keynes.

When I visited, the shutters were about to come down for the day — but that did not deter yet another potential buyer from ducking in to peruse the line of vehicles crammed into its small boutique shopfront.

The customer explained that had always been sceptical about battery-powered cars until a neighbour purchased one recently. Now he was seriously interested. He left with several questions answered, and details of several local dealers who could offer test drives. He was one 64,000 visitors to the shop.

The centre’s manager, Ted Foster, knows of at least 100 sales that directly resulted from a visit to his shop but estimates that the effects of it will ripple far wider. “This will hopefully influence people when they come to buy a car in two, three years,” he says.

How much does it cost?

While the sticker price remains stubbornly high, the running costs of electric vehicles are tiny, meaning car buyers need to consider the “total cost of ownership” rather than the initial price.

The new Nissan Leaf costs about £27,000, while the Nissan Micra — the equivalent sized car with a petrol engine — costs just shy of £13,000.

The government pays £4,500 towards the upfront cost of a new electric car, a grant that is likely to be tapered beyond 2020 as adoption increases. Prices are also likely to fall as more options come on to the market, creating choice in each product segment, from family cars to spacious SUVs.

But the real advantage lies in the running costs, with big savings on fuel costs, servicing, and car parking, not to mention the value of free access to toll areas such as London’s Congestion Charge Zone (currently £11.50 per day).

When Richard Mountain, a chartered surveyor from south London, traded in his old Jaguar for a BMW i3, the cost of his local council parking permit fell from £350 a year to just £35.

Service costs are also less, partly because electric vehicles also have a fraction of the moving parts of their internal combustion counterparts. After breaking down an electric Chevrolet Bolt into its component parts, investment bank UBS estimated there were 16 moving pieces inside the car, compared to 136 in a petrol-driven VW Golf.

Ted Foster at the Chargemaster centre in Milton Keynes estimates that lifetime servicing costs for an electric Renault Zoe will be half that of a Clio — the equivalent model with an engine — while fuel bills are almost non-existent if charging at home.

“The number one question we get is always cost,” he says. “Simply, people don’t know how much they are paying for energy in their current cars.”

Will it hold its value?

In reality, very few people will buy a new electric car outright.

The way that almost all new cars — and an increasing number of used cars — are bought in the UK is through a personal contract plan (PCP), a pay-monthly credit scheme that spreads the cost of a vehicle’s depreciation across a period, typically three years. This benefits premium cars, which hold their value better, but presents a problem for electric vehicles.

While a traditional car is valued based on its mileage and age, and the engine and its parts can be opened up and visually inspected, electric cars are more difficult. No one knows how to calculate the depreciation of the battery.

CAP HPI, the body used by the industry to value second hand vehicles, still uses age and mileage to calculate battery car values.

“We value the whole car, we don’t try and value the battery separately,” says Chris Plumb, head of electric vehicle valuations.

Inherent to the question is how much of its charge the battery has lost. If a battery that once offered 100 miles of range can only reach 85, the potential uses for the car diminish greatly.

Residual values on early Nissan Leafs — the first major electric car sold in Europe, launched in 2010 — were at one point only 17 per cent after three years.

But early fears that batteries would degrade were overblown, and the values of second hand electric vehicles have been quietly climbing.

For example, car pricing data shows that you could have bought a one year old Nissan Leaf in September 2016 for £10,300. Yet the same car would have sold in August 2018 for £11,800, despite being two years older.

Angus Hanton, an entrepreneur who co-founded the Intergenerational Foundation, has owned a Leaf for five years, and says its once-90 mile range has only dropped to 82. “We’re actually very pleased with that,” he says, driving through the speed bump-strewn roads around Dulwich.

The increased availability also means that cars are beginning to trickle into the world of used vehicles, a market three times the size of new car sales.

“We’re seeing more of them coming into the used car market, and that’s honestly what most people are looking at,” says Gareth Dunsmore, head of electric vehicles for Nissan Europe.

After several years valuing used electric cars, Jonathan Porterfield, a specialist who lives on the Scottish island of Orkney, also believes they are worth far more than current estimates. “There is a huge gulf between actual fact and the gut reaction of the motor trade,” he says. “All the indications are the [Nissan] Leaf will be full of rust holes way before the battery is useless.”

To ease the concerns, some manufacturers offered to lease batteries to consumers — leading to the unusual situation of motorists paying one monthly sum for the car, and another for the battery that powered it. When selling it on, the car’s value fell, but monthly payments for the battery continued.

The practice caused chaos among valuation firms, and finance companies offering PCPs, and it was eventually dropped by almost all manufacturers.

Now, most manufacturers offer an eight-year warranty on a new battery instead, says Chris Plumb at CAP HPI, a data provider to the motor trade. “That just offers peace of mind that whatever happens it’s under warranty.”

Will it run out of battery?

The single greatest concern with electric vehicles remains their range. Worries that a battery will run out before reaching a charging station have led to the industry maxim “range anxiety”.

Most manufacturers with electric vehicles offer a recovery service to stranded motorists — often free on the first pick-up, on the basis that a customer won’t let it run down a second time.

“It’s still the biggest question I get,” says Mr Porterfield, who acts as an unofficial car scout for Orkney residents, often travelling south to buy used electric cars from auctions or other dealers, before driving them back to either John O’Groats or Aberdeen to get a ferry to the island.

He makes the journey by hopping between charging stations at motorway service areas. “Everyone thinks I’m slightly mad, but I do it to prove the point that you can do it,” he says. Sitting in service areas also takes its toll. “Honestly, bladder anxiety is more of an issue than range. People say they will wait until the range is 200 miles before they buy one, even though they drive 22 miles a day.”

This means most people charge their cars overnight at home, or at work, and only visit public charging stations very infrequently. Although there are more than 10,000 public charge points, with more going in all the time, this still poses a challenge for people without driveways.

When Ian Plummer, a former VW and Renault director who is now a senior executive at Auto Trader, looked at buying a Tesla, he discovered there were no charging posts close to his home in North London. “There were two about 400 meters away, but they were almost always busy,” he says. So he bought a Porsche.

Efforts are under way to solve this conundrum, which affects almost half of urban homes in Britain, with recent schemes including one in London to turn lamp posts into charging points.

The cost of home charging, which Chargemaster estimates at £570 per year based on paying 12p per kwh to top up a 40kwh battery three times every week, is far below petrol costs, which the AA estimates as being at least £1,400 a year.

The economics alone, which has tipped in favour of electric cars for some time, will not be enough to spur large numbers of today’s car buyers to convert to battery powered vehicles. Electric cars need a new consumer mindset, from being prepared to plug in and charge at a service area, to pulling off silently while checking for un-suspecting pedestrians.

But once they have embraced the future, electric car owners often find they have embarked on a one-way street: they never want to return to the dark days of petrol.

Electric cars unplugged

With only two miles left on the battery, panic was beginning to set in. A few weeks ago, I was test driving a Tesla, on loan from the company to make an FT video showing the benefits of electric vehicles.

But crawling along the A4, with the drained battery indicator glaring at me, I was experiencing one of their largest drawbacks: range anxiety. When fully charged, the car has a range of 300 miles — more than adequate for even the most intrepid day trip.

The previous day I drove to the Silverstone racing circuit for filming, charging it briefly on the way back home at a public topup point in Milton Keynes.

But arriving home with 10 miles left in the “tank”, I committed the cardinal sin of battery vehicles — forgetting to plug it in.

A three pin socket would not do much for the battery in a single night, but would have given me another 20 or so miles of range — enough to reach one of Tesla’s Superchargers that are dotted across the country and programmed into the on-board navigation system.

Now, with rain streaking down the windscreen, I was looking for a car park, or a hotel, or anywhere that might have a public charge point to avoid grinding to a halt on a main road.

An open air shopping centre presented the best chance — but the charging post nestled away in the back corner was from a different company to the one I used the previous afternoon at Milton Keynes, so I did not have the right app. By this time, two unimpressed Tesla employees were en route in a back-up car.

My unfortunate experience has been shared by several owners.

Isabel Hardman, a political writer who splits her time between London and her home in Cumbria, has several times been let down by faulty charging stations at motorway service areas.

“It’s perfect when you’re out and about and the service area works,” she says. “But if you arrive and the chargers are out of order then you’re snookered.”

She says that a four-hour drive to Scotland turned into a “seven hour nightmare” because of several faulty points, forcing her to limp along at low speed to the next service area.

Another time, she had to wait for three hours for Nissan’s recovery service, which then towed her to a slow charger that would have taken all night to replenish the vehicle.

“The infrastructure is bad, especially in the north,” she says. “It’s still really in its infancy, whatever anyone will tell you.”

But despite the drawbacks, even the horror stories, she will never return to petrol.

“Oh no, I could never go back,” she insists. “It’s a beautiful car to drive, so smooth.”

Comments