A Republican tax plan that will help the rich and harm growth

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

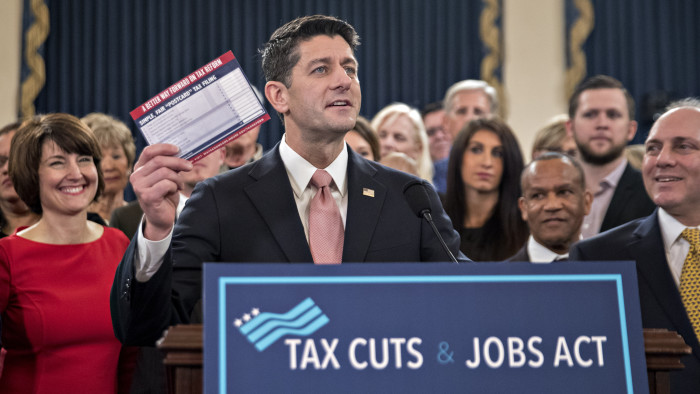

With the release late last week of the Republican tax proposal, the most important debate on tax in the US in a generation is now in full swing.

Most reasonable experts will agree that tax reform has the potential to spur investment and raise wages, while at the same time simplifying the system and increasing its fairness and legitimacy. The right issue for debate is not the desirability of tax reform or even of business tax reform directed at spurring investment. It is instead the likely economic effect of particular proposals.

Unfortunately, the proposal from Republicans in the House of Representatives on offer now may well retard growth, reward the wealthy, add complexity to the tax code and cheat the future even as it raises burdens on the middle class and poor. There are three aspects of the proposal that I find almost inexplicable, except with reference to the power of entrenched interests.

First, what is the rationale for tax cuts which increase the deficit by $1.5tn in this decade and potentially more in the future, rather than revenue neutral reform such as that adopted in 1986? There is no present need for fiscal stimulus. The national debt is already on an explosive path, even before taking account of large new spending needs that are almost certain to arise in areas ranging from national security to infrastructure to addressing those left behind by globalisation and technology.

Borrowing to pay for tax cuts is a way of deferring, not avoiding, pain. Ultimately the power of compound interest makes even larger tax increases or spending cuts necessary. But in the meantime debt-financed tax cuts raise the trade deficit, and reduce investment thereby cheating the future.

Second, what is the compelling case for cutting the corporate rate to 20 per cent? Under the proposed plan, for at least five years businesses will be able to write off investments in new equipment entirely in the year they are made. So the government is sharing to an equal extent in the costs of and the returns from investment, eliminating any tax induced disincentive to invest. The effective tax rate on new investment is reduced to zero or less, before even considering the corporate rate reduction. Corporate rate reduction serves only to reward monopoly profits, other rents or past investments. After the trends of the past few years, are shareholders really the most worthy recipients of a windfall?

Proponents of the House approach defend it by pointing to international considerations. Unfortunately the “territorial” approach pushed by the House could, by renouncing the objective of taxing the global income of US companies, actually work to encourage offshore production. Wouldn’t it be much better for the US to lead an initiative to prevent a race to the bottom in global corporate taxation than to try to win a race to the bottom?

Third, why include new complexities that help the richest taxpayers while taking steps that hurt middle income families? Why should passive owners of businesses that are already avoiding corporate tax get a big rate reduction to 25 per cent, when those who actually operate and work in such businesses pay at a higher rate? What is the rationale for eliminating the estate tax when it is paid by only 0.2 per cent of households?

At a bare minimum, if such provisions are to be adopted one would assume that they would be paid for to the maximum extent possible through steps like eliminating the carried interest loophole, or loopholes that enable real estate tax shelters. Not so. The proposal instead goes after measures like the adoption tax credit, deductions for major medical expenses and the deductibility of student loan interest. These seem like far better benefits to preserve than carried interest.

Instead of pursuing the current plan, Congress should return to the 1986 approach of revenue neutral tax reform, with an effort made not to adversely affect the progressivity of the tax system. This would enable what is most important now — strengthening incentives for investment in the US relative to other countries, while at the same time raising the legitimacy of the tax code.

It is possible, though I doubt it, that the questions I have raised here have good answers. And there may be reasons why 1986 is an inapplicable model for today. What is certain, though, is that a once-in-a-generation debate is under way. Even those who disagree on policy should be able to agree on the importance of not taking decisions until all relevant analysis can be completed.

The writer is Charles W Eliot university professor at Harvard and a former US Treasury secretary

Comments