Apps: Growing pains

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Stuart Hall confesses that when he sat down to write his 7 Minute Workout app, he had to use Google to find out what a plank exercise was. A year later, the Australian developer has made A$60,000 ($56,000) in revenue from an iPhone app that took him just six hours to code.

“I put very little work into an app and launched it into a huge market [in 2013],” he says, cashing in on the trend for little-and-often exercise.

For the first few years after Apple’s App Store launched in 2008, such stories were commonplace. Anyone with a modicum of technical talent, it seemed, could piggyback on the iPhone’s rapid growth. Early smartphone adopters were happy to spend a couple of dollars on a well-designed to-do list or weather app, and Angry Birds was flying high.

“There was this whole idea that there is a gold rush,” says Mr Hall, who now runs an app analytics service called Appbot. “You tell people you’re an app developer and they think you should be rich.”

But 7 Minute Workout is beginning to look like the exception rather than the rule. Independent developers fret that only the biggest companies can get noticed on the app store now. What was once a thriving cottage industry has been industrialised, with most apps receiving few if any downloads.

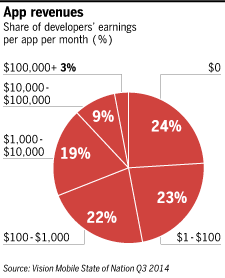

A study last month of more than 10,000 app makers by market analysts VisionMobile found that 1.6 per cent of developers make more than the other 98.4 per cent combined. While the research estimates there are almost 3m mobile developers in the world today, more than half make less than $500 per app per month.

“It seems extremely unlikely that the market can sustain anything like the current level of developers for many more years,” it concluded.

A separate study from Deloitte found that almost a third of smartphone users do not download any apps in a typical month.

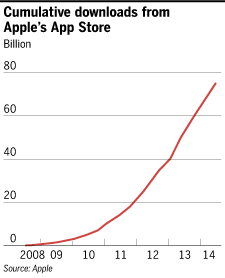

On the face of it, this dynamic is puzzling. A growing majority of people in western Europe and North America now own smartphones of increasing sophistication and capability. Owners of iPhones and iPads have downloaded more than 75bn apps in the past six years and Apple’s online store holds the credit card details of 800m people. Google Play, the app store for Android devices made by the likes of Samsung and HTC, has closed its longstanding gap behind Apple in app activity and spending. These should be boom times for developers.

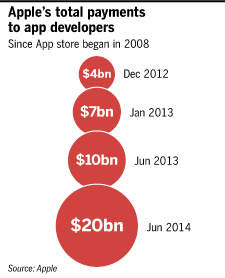

According to the smartphone makers, they are. Apple says the app economy has created about 1m jobs in Europe and that it has paid more than $20bn to developers since the app store launched in 2008. A report commissioned by Google forecasts revenues from producing smartphone applications to exceed $51bn by 2025.

Yet amid the apparent wealth, the mood is gloomy among the independent coders and small businesses that make most of the apps now available for Apple and Google devices.

Luc Vandal, founder of Montreal app shop Edovia, sums up the feeling of many: “Let’s face it, the app gold rush is over.”

If correct, there could be problems for more than just the geeks who depend on app development for their livelihoods. Apple and Google rely on thriving app stores to give people reasons to buy, use and upgrade their phones or tablets.

The diversity and ease of mobile software has helped small screens to overtake PCs as the world’s most popular computing devices. At a time when there is concern that new technologies are destroying more jobs than they create, many had hoped the apps world would continue to create employment.

Part of the problem stems from the success of the app store itself. Back in 2008 or 2010, developers say, the best apps rose to the top of the charts – even those that charged a dollar or two. Now, with millions of apps to choose from, the stores are dominated by those companies that can afford to invest heavily in online advertising.

Social networking apps such as Facebook, WhatsApp Messenger, Instagram and Snapchat benefit from a viral growth engine that more utilitarian kinds of software cannot hope to compete with. Even Candy Crush Saga ’s huge popularity – the game which at its peak was played more than a billion times by more than 90m people every day – has waned, and its creator King warned in a recent earnings call that its other games were failing to make up the difference.

“In the last year, there hasn’t been a single real blockbuster app,” says Tero Kuittinen, managing director at Magid Associates, a consultancy, and adviser to several mobile start-ups, “and every other app has a drastically reduced lifespan.”

On a smartphone’s small screen, people do not spend much time browsing or researching. They simply look at what everyone else is downloading.

“The app store is a hit-driven business, like the music or movie industry,” says Ouriel Ohayon, chief executive of Appsfire, a mobile advertising company. “The biggest obstacle for the long tail of apps is precisely what has driven the success of the app store: the tyranny of the top charts.”

That dynamic has fuelled a black market in app downloads. Shady marketing firms offer desperate developers a “guarantee” that their app will appear in the charts, using automated server farms. Some employ rooms full of people doing nothing but downloading apps.

Adding to the visibility problem is the ease with which other companies can copy popular apps. Flappy Bird’s abrupt removal from the app store in February, after its developer said its surprising success had “ruined” his life, led to dozens of “tributes” and clones flooding the charts.

It took only 21 days after the release of Threes, a puzzle game that its creators spent more than a year developing, for the first copycats to appear.

“The branching of all these ideas can happen so fast nowadays that it seems tiny games like Threes are destined to be lost in the underbrush of copycats, me-toos and iterators,” its two developers complained recently.

If developers cannot buy their way into the top 10, or if they find their ideas are being ripped off, they must hope that the inherent quality of their app will stand out enough that Apple or Google features them for promotion on their stores’ front page. These slots – driven largely by an algorithm in Google Play and chosen by editors on the iOS App Store – cannot be bought or rigged.

A recommendation from Apple or Google does not always give a lasting boost these days, even for larger and well-resourced companies.

But what these storefronts are increasingly highlighting is the growth of smaller categories of apps that still hold growth potential. Apps for school supplies, wedding planning or filing taxes are unlikely ever to touch the top charts, but at certain times of year can prove more lucrative for serving a specific need.

“The people that make money seem to be in much smaller niches,” says Mark Wilcox, analyst at VisionMobile.

Yet some of these niches are poised for rapid growth, from health and fitness to corporate apps and even new mobile payment services, as Google and Apple look for apps that can help them open new sources of demand for their devices. Amid the pessimism, app-store optimists believe that the market is not dying but simply entering a new phase.

Both Apple and Google have launched app platforms dedicated to health, named HealthKit and Google Fit respectively. These super-apps will gather data from other health and fitness apps into a central hub. Both are central to the technology companies’ hopes that wearable devices will propel the growth of iOS and Android.

They have also given an extra boost to apps that log running, cycling, calorie intake or sleep. Moves, which allows users to count the number of steps they walk in a day, was acquired by Facebook this spring. Withings’ Health Mate uses the smartphone camera to take a heart-rate reading and MyFitnessPal is taking on Weight Watchers by helping people track their eating habits to shed some pounds.

“You can see how both [Google and Apple] are raising their voices on the health and fitness area,” says Cédric Hutchings, chief executive of France-based Withings, which raised $30m in venture funding last year. “There is a race between these two big ones that is really beneficial for us.”

Apple’s recent deal with IBM to sell iPhones and iPads into larger companies has also stimulated a growing market for business and productivity apps that go beyond a simple to-do list or word processor.

Jeremy Olson, founder of app design company Tapity, recently launched Hours to help freelancers track the time they have spent on various projects. It costs $10 – a high-priced outlier in a store dominated by free apps. “We tried building apps before for 99 cents and we’ve got a bit of volume, but it’s hard to be sustainable,” says Mr Olson. “We wanted to try a premium strategy. Hours is primarily a business app and people expect to pay a bit more.”

SFCD, a New York-based digital agency, says even a simple app takes 25 days to create and costs a client about $37,000, based on an hourly rate of $175-$200. A more sophisticated app, using the cloud to synchronise data between devices, might take almost 100 days, costing up to $200,000. It would take an awful lot of 99-cent apps to break even on an app costing hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“We decided to charge a fair price and it worked out a lot better than I thought,” says Mr Olson. “The opportunity, while it is harder, is bigger than it ever was before . . . I think Hours could be a $100m business someday.”

Even the seemingly saturated photo-sharing app market is still seeing new entrants, in the wake of Instagram and Snapchat’s success.

Storehouse, a San Francisco start-up, lets users read and create photo-centric stories on the iPad that are part blog, part magazine, part memoir. Fuelled by $7m in venture funding, co-founder Mark Kawano believes the only way Storehouse can succeed as a business is by giving the app away for free, and making money beyond the App Store itself – perhaps through advertising. “We could charge for it and be profitable on a very small scale but that would give copycats an opportunity,” he says.

Just as investors are hoping that there is more growth yet to be wrung from the smartphone market, many developers remain optimistic that the next iPhone or Galaxy will bring innovations that they can build upon.

“Apple’s payment system will launch a new wave of apps,” says Mr Hall, the Australian workout app developer, of the widely rumoured new iPhone feature. “It’s a continuously evolving thing. You just have to keep moving.”

Unbundling

A controversial trend among Silicon Valley app makers is to split up one monolithic app into discrete downloads for specific purposes. These app “constellations” are intended to improve the ease of use for customers, by breaking out popular features rather than burying them in menus. This also has the side-benefit for their developers of colonising another slot on a user’s smartphone homescreen that might otherwise be taken by a rival.

Facebook is the most prominent case of this trend, unbundling its “big blue app” into several simpler apps, including messages and photos. Dropbox’s Carousel photo-sharing app and Foursquare’s Swarm for sharing location “check-ins” are other examples, though they have yet to achieve the same popularity as their parent apps.

However, Facebook has upset many users by forcing them to download Messenger in a recent app update. The tactic succeeded in driving Facebook Messenger to the top of the app-store charts – but at the cost of tens of thousands of angry one-star reviews with some accusing the company of a lack of respect for user feedback.

Health and fitness

Google Fit and Apple’s forthcoming Healthkit, part of September’s iOS 8 update, have added momentum to a growing market for fitness and health-tracking apps. Big sports brands such as Nike are jostling for position against start-ups such as Runkeeper, Strava and MapMyRun while MyFitnessPal and Jawbone’s UP allow the weight-conscious to log their meals.

Apple’s central Health app will bring data from all these providers into a central dashboard, through which users can then share their health data between apps or with doctors. This new iPhone app will also bring in information from wearable devices such as Fitbit or Nike Fuelband.

By asking users to trust them with their most intimate personal information, Apple and Google hope to turn smartphones into personalised fitness trackers that help alert physicians to problems without needing to visit a surgery.

Both will link to their own wearable devices, from Google’s Android Wear smart watches to Apple’s rumoured fitness tracker, which is expected to be launched before the end of the year.

Enterprise and productivity

Tim Cook, Apple chief executive, told investors last month that he believes there is “substantial upside” for the iPad in corporate markets, which is why he struck a deal with IBM to help sell mobile devices to enterprise customers. Developers hope Mr Cook is right, since the business market is much more likely to spend money on apps than individual consumers.

Microsoft’s Office for iPad app enjoyed more than 12m downloads in its first week, while younger collaboration companies such as Box, Huddle, Quip and Slack rely on mobile apps to keep teams in touch.

While smartphones come loaded with apps for managing messages, calendars and contacts, that has not stopped developers from trying to better Apple and Google’s defaults.

Humin and LinkedIn’s Connected apps try to organise contacts by how you know them, for more efficient networking, while Fantastical and Tempo try to add even more to the diary, offering everything from traffic advice on how to get to a meeting to a briefing on who you are going to meet.

Copycats

Flappy Wings, Snappy Bird, Flappy Flyer, The Impossible Flappy Game . . . Online education site Udemy offers a two and a half hour class in making clones of the wildly popular Flappy Bird game without needing to write a single line of code.

While many are removed by Google and Apple, a copycat problem continues to plague their app stores. The door to widespread copying was opened by the shift from paid apps, costing 99 cents or 69p to download, towards free downloads that are funded by advertising or

in-app payments for upgrades. Many developers feel the guardians of the app stores could be doing more to promote original apps, but asking Google to change its search algorithm is rather harder than cloning Flappy Bird.

The copycats present more than just a commercial risk to more innovative developers. According to one estimate from security firm McAfee, more than three-quarters of Flappy Bird clones present a threat of mobile malware, hijacking the device to send unauthorised text messages or tracking their location.

Comments