Northern Rock: modern-day parable

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

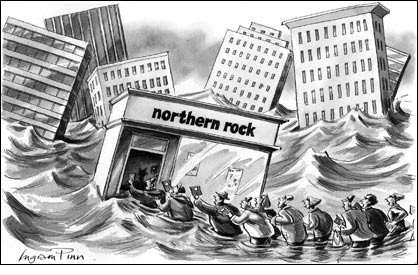

The banks, we used to think, are as safe as houses. The trials of Britain’s Northern Rock have left neither looking especially secure. After years in the stratosphere, house prices now look set to succumb to the force of gravity. And the choice between the bank vault and the mattress no longer looks quite so one-sided.

You could say that the fall of Britain’s fifth largest mortgage lender is a familiar enough tale. Start with a liberal dose of credulity and greed, stir in complacency and the calculated complexity of today’s capital markets and you have the classic ingredients for a financial failure.

A visitor from elsewhere might wonder, of course, what all the fuss is about. We are not talking, after all, about the collapse of Citibank or even, dare one say it, Barclays or Lloyds TSB. By global standards, Northern Rock is a pretty modest institution. Few believe the name can survive the past few days. But then few beyond its base in the north-east of England, probably, will miss it.

For all that, Northern Rock’s fall has become something of a parable for the times: a story of the insecurity, mistrust and powerlessness that often seem to best describe our world. It speaks to the fragility of the international system we call globalisation; of the capacity of fear to shape events; and of governments powerless to halt an erosion of confidence in once solid institutions.

Bank failures have been with us for as long as we have had banks. The history books are littered with accounts of depositors falling prey to financial chicanery and credit bubbles. And you can still find people in the City of London with personal recall of past collapses: the secondary banking crisis of the early 1970s; the closure of the London-based Bank of Credit and Commerce International after it turned out to be a front for all sorts of nefarious activities; and the demise of Barings, one of Britain’s most revered financial institutions, at the hands of a single rogue trader.

Yet, the manner and circumstance of Northern Rock’s troubles were different. The casualties of this latest affair are still being counted. One looks likely to be Britain’s system of banking regulation and deposit insurance; a second (unfairly) may be the reputation of Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England. Gordon Brown, the prime minister, has his fingers crossed that his re-election prospects will not be the third. The fourth, though, may turn out to be the most enduring: the further destruction of trust.

What made this crisis special was television: the hour-by-hour images of anxious and angry depositors crowding the branches of Northern Rock the length and breadth of the land. When Britain last witnessed a run on a bank, the menfolk still dressed in top hats and tails. In those days, there were no television cameras to record the havoc.

This time, as depositors at Northern Rock ignored the fumbling assurances of ministers and financial authorities alike, there was a temptation to put it all down to an outbreak of mass hysteria. In reality, the people queueing to empty their accounts were behaving entirely rationally.

Most obviously, those with sizeable savings were not fully insured. Yet there was more to the rush than that. Everyone knew that the other banks were refusing to lend to Northern Rock. So why should they, as individual savers, be more trusting? As for the official protestations that the bank was solvent, well, what else would they say? For much of the time the government has anyway seemed powerless. If not, why had it not prevented problems on the American mortgage market from threatening to bring the British banking system to its knees? Only when Alistair Darling, the chancellor of the exchequer, offered an extraordinary guarantee covering every penny saved in every bank were people willing to take the government’s word.

Conventional wisdom now is that Northern Rock was an accident waiting to happen. Its business model – based on short-term borrowing in the wholesale markets to fund long-term retail lending – assumed infinitely plentiful liquidity. Once confidence had been jolted by America’s subprime problems, Northern Rock was always going to face a funding crisis.

If it is so obvious now, the lay person might ask, why was it not so earlier in the year when Northern Rock was boasting of its success as Britain’s fastest-growing mortgage lender? Did anyone tell depositors that a couple of months of choppy conditions in global credit markets might sweep it away? Nor could anyone be expected to draw comfort from protestations that this was a crisis made elsewhere.

Mr Darling could not be faulted when he said that the British economy has been in robust health, or that the credit squeeze had its roots in mistakes made in the US. That, though, seems cause more for alarm rather than comfort. Measured against the trillions of dollars that wash daily around global capital markets the losses in the American subprime mortgage market are minuscule. How, if everything else was fine, could a bank like Northern Rock be brought to its knees by some careless lending 3,000 miles away on the other side of the Atlantic? Are we that vulnerable?

Mr King concedes that those outside the financial services industry must have watched recent events unfold with “utter bemusement”. A bemusement, he might add, that fully explained the anxieties of those in the queues outside Northern Rock.

I am not sure, though, that bemusement is quite the right word. Justified suspicion might be better. Perhaps the crowds sensed that nothing is straightforward any longer. The reason why the crisis crossed the Atlantic, after all, lay not so much in the scale of the subprime losses but in the calculated opacity of today’s financial markets. The squall became a hurricane because the risks of subprime lending had been carefully concealed in the mortgage securitisation market and then scattered to the winds. No one knew where they had come to rest.

I can already hear the sophisticates sigh. What should we expect? A return to a world where every bank deposit is marked in a ledger against a precisely matched loan? What, apart from anything else, would the commercial banks do with all their highly paid mathematicians?

In one respect this is obviously right: it is too late, even if we wanted to, to roll back the frontiers of financial innovation. The integration of global economies and markets may feed our insecurities, but it also makes us richer. But plainer folk, and I include myself here, are likely also to draw another conclusion. Why should we trust anyone?

Comments