The leveraging of America: how companies became addicted to debt | Free to read

Simply sign up to the Coronavirus economic impact myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The year was 1973 and as the Vietnam war wound down, an oil embargo was threatening the very foundations of the US economy. Petrol stations were running dry and highways began to empty. At Hertz, the car rental company then known for its pioneering computerised booking system, executives realised that transport companies would inevitably be among the first casualties. Hertz’s response? It loaded up on debt.

Within weeks of the embargo starting, Hertz was selling off the gas guzzlers that made up three-quarters of its fleet, and borrowing heavily to replace them with smaller, more efficient cars. The gamble proved wildly successful.

The next year, as an oil price shock ravaged competitors and triggered a bout of “stagflation” as high inflation combined with low growth, Hertz’s revenues and profits hit new records. Soon, the company’s advertising department hired a young athlete named OJ Simpson and proclaimed itself “the superstar in rent-a-car”.

The New Social Contract

Coronavirus has exposed the frailties of our economic and social model. In a series of articles this week, the FT explores the problems and difficult solutions we will confront after the pandemic.

Martin Wolf on the importance of citizenship

Will low-paid workers ever get a raise?

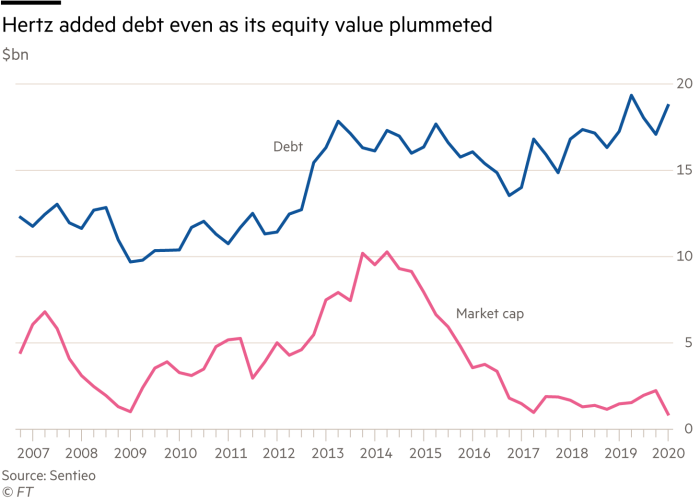

Yet almost half a century later, Hertz is bankrupt, the victim of a coronavirus pandemic that has brought large parts of the global economy to a standstill. The company, which employed 38,000 people last year, and operated from about 12,000 locations, was unable to escape the weight of a $17bn debt pile. The bet that prospered in the 1970s has come unstuck in the 2020s.

Other rental chains have taken out new loans to ride out the drought in travel bookings, but Hertz’s borrowing capacity was already spent: after 15 years of aggressive financial engineering, it owed $12,400 for every car worth $10,000. Much of the money came from complex financial instruments that allowed creditors to demand their cash back when the company could least afford it.

Hertz’s demise has drawn attention to the relentless build-up in corporate debt in the US, where companies now owe a record $10tn — equivalent to 49 per cent of economic output. When other forms of business debt are added in, including to partnerships and small businesses, that already extraordinary figure increases to $17tn.

Even before the pandemic, the level of corporate leverage was beginning to cause alarm. At the end of last year, the IMF issued a striking warning: as much as $19tn of business debt in eight countries led by the US — or 40 per cent of the total — could be vulnerable if there were a “material slowdown” in the economy, a scenario that, if anything, now seems tame.

With companies filing for bankruptcy at the fastest pace since 2013, the American authorities have been forced to take exceptional measures to save jobs and prevent more companies from collapsing. The Federal Reserve pledged in April to buy trillions of dollars of debt, much of it owed by the corporate sector, while the government has set up a $500bn small business loans programme.

This is the second time in just over a decade that the Fed has mobilised the full force of its balance sheet to put a floor under creaking credit markets.

Unlike during the 2008 crisis, the financial sector was not the immediate cause of the turbulence: investors can legitimately claim that they have been confounded by a once-in-a-century event. But fearing a much greater meltdown, the Fed has again found itself obliged to support a wide range of debt instruments, some of which have questionable credit quality.

Amid the prospect of a new generation of “zombie” companies unable to pay their interest bills, the pandemic is reviving the debate about whether it makes economic sense for the corporate sector to have taken on such a large volume of debt — and whether there is a way to unwind it without causing a broader crisis. The financial crisis prompted a similar discussion about excessive financial engineering, but the response in the decade since that crisis has been to increase leverage, not to wind it down.

This addiction to debt has developed over five decades. Encouraged by the tax system, and perhaps with an eye on their own pay, corporate leaders were quick to embrace the trend. Pension funds and insurance companies bought the debt in bulk, while private equity firms — including Clayton, Dubilier & Rice, which acquired Hertz in 2005 — put together leveraged buyouts as if they were running an assembly line.

The result has been a dramatic change in how the US economy channels savings into the financial capital that fuels growth. Arguably, it made America more competitive, as public companies have slimmed down or gained focus, while private equity firms perfected the art of eliminating fat from company payrolls — as well as equity from their balance sheets. Yet critics believe that the huge focus on financial engineering in recent decades also contributed to the weak productivity of the US economy.

The pandemic has underscored the fragility of an economy built on corporate debt in a time of crisis. Many companies now risk digging themselves a deeper hole: new loans might help them through the worst period of lockdowns, but it means they will be entering a potentially weaker phase of economic growth with even higher debts.

“It’s corrosive to a well-functioning market,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at the analytics arm of Moody’s. “It’s going to start eating away at the productive capacity of your economy. Business models have changed, but you’ve got companies still surviving and getting credit, and [they] are not going to adjust. You’re creating longer-term problems.”

Engineering a new financial reality

The leveraging of America was little more than an idea until a young bond salesman reimagined the function of the credit markets, and set in motion a debt machine that would change the rules of business.

Michael Milken’s insight was that lending to risky companies at high interest rates could be more profitable than earning reliable but meagre returns from the debt of industrial champions. By the late 1970s, he had graduated from trading the deeply discounted bonds of struggling companies to inventing a form of corporate venture capital, issuing debt for companies whose prospects were so uncertain that their bonds were rated as junk from the start.

To this day, many who worked with Mr Milken at Drexel Burnham Lambert regard themselves as financial revolutionaries whose innovations brought fading industries to life and financed the rise cable television, the reconstruction of Las Vegas, and more besides. Former Drexel board member Chris Andersen once described a discussion among bond market veterans about the impact of the bank’s innovations. Someone “called for a vote on who had the greatest positive influence, Michael Milken or Mother Teresa,” he recalled. “Milken won hands down.”

The craze for debt spread far beyond junk bonds, which were being issued at a rate of $25bn a year by the end of the 1980s, up from barely $1bn at the beginning of the decade. Industrial conglomerates, utilities and other investment grade borrowers also loaded up. Even far smaller companies got in on the act, taking out loans that were often repackaged into securities that could be traded on the markets. Insurance companies and pension funds — many of which have regulatory reasons to avoid investing in equities — lined up to buy it all.

Companies faced a number of incentives that pushed them in the direction of taking on more debt. “Equity financing has double taxation: you pay corporation taxes, and then shareholders pay tax on the dividends.” says Markus Brunnermeier, an economics professor at Princeton University. “Whereas if you pay interest, the expense is tax-deductible. There is a huge distortion coming from the tax system, and economists have argued for decades that it is unwise.”

Shareholders cheered on the extra borrowing. Some were persuaded by the work of Harvard professor Michael Jensen, who argued debt financing would keep executives honest by forcing them to meet quarterly repayments instead of squandering the company’s cash flow on uncertain growth initiatives or personal perks.

Executives, too, had financial incentives to jump aboard. The value of stock options and similar pay schemes “rises if a risky project pays off, but cannot fall below zero if things go wrong”, Alex Edmans, a professor at London Business School, told a government inquiry into executive pay. “So the CEO has a one-way bet.”

Wall Street turned America’s corporate debt burden into its most attractive product. That would have profound consequences for how companies are run.

Wall Street’s favourite fuel

The $15bn private equity deal that took Hertz private in 2005, led by Clayton, Dubilier & Rice, was the second-biggest on record. It also turned out to be one of the shortest; just nine months later, Hertz returned to the stock market.

But even that brief period under private equity ownership transformed Hertz’s balance sheet. Before the 2005 buyout, interest payments on the company’s borrowings absorbed about one-fifth of its operating income. Under new ownership, Hertz added $4bn to its debt pile, Moody’s cut its rating to junk, and the average interest rate on the company’s borrowings increased. After that, interest absorbed nearly three-quarters of the company’s operating income.

It took a sprinkling of Wall Street ingenuity to raise the additional $4bn. To make it more attractive to investors looking for “safe” assets, much of the debt took the form of “asset-backed securities”, a structure that aims to ringfence cash flows for the benefit of lenders and make it easier to seize collateral in a bankruptcy. Then, the debt was sliced up, with the layers on the top having first dibs on cash if Hertz were ever to fall short. Billions of dollars of the debt carried the highest triple A rating, even after Hertz itself was downgraded.

This exercise in financial engineering was a triumph. When Hertz returned to the stock market in November 2006, its equity was worth about $4bn, roughly double what the private equity firms had paid for it a year earlier. When CD&R sold its last shares in 2013, the firm listed its achievements at Hertz, which it said included improving operating efficiencies, changing the way the company bought and sold cars and creating a flexible capital structure that withstood the great recession.

But one powerful legacy was the vast pile of debt, and long after the private equity firms had gone, Hertz’s management team kept adding to it. By last December, borrowings accounted for $17bn of the rental company’s $19bn enterprise value, with only a sliver of equity on top. If the economy ever faced a severe reckoning, Hertz would be among the first to fall.

Temporary reprieve

More than 3,000 US companies filed for bankruptcy between January and late June. For tens of thousands more that may be teetering on the edge, Mr Zandi, the Moody’s chief economist, identifies what he calls “a Hobson’s choice: do I make my debt payment on time, or do I [keep] investment and jobs?”

The fate of millions of livelihoods — and America’s future economic productivity — therefore depends on whether over-indebted businesses can extricate themselves from danger before they are forced to prioritise their own survival.

“What we have done is postpone this, by adding to the debt,” says Mohamed El-Erian, who spent seven years as chief executive of Pimco when it was the world’s biggest bond fund. Since the Fed announced its bond-buying programme in March, “we’ve seen an explosion of corporate debt, together with an explosion of financial engineering. The influence is huge, because they [the Fed] are non-commercial, they are not price sensitive, and they have an infinite printing press.”

Yet few believe that reprieve can last for ever. Unless struggling businesses once again see their revenues begin to rise, many will confront a stark choice between orderly restructuring and default.

For those that choose the first option, one source of possible help is the private equity firms — despite the role many of them played in building up corporate leverage in the first place. “They’ve got a lot more operating chops than they did 12 years ago,” says University of Chicago professor Steven Kaplan. “If there's a company that has going concern value and needs to be restructured . . . there are billions and billions of dollars of funds getting ready to put money in to help with that process.”

The authorities are effectively betting that a revival in the economy will allow many companies to grow out of their new debts. “By subsidising the debt markets, we were able to avoid a liquidity problem becoming a solvency problem,” says Mr El-Erian. “That’s exactly what central bankers will tell you: we’re going to keep finance going through higher debt — and we hope that higher debt will be validated by growth coming back.”

It is a fragile hope, but one at least partly vindicated by the course of the crisis so far. Days after the Fed’s extraordinary intervention in March, car rental group Avis seized a lifeline, issuing $500m in junk bonds that could enable it to weather the pandemic.

For Hertz, however, there was no rescue. While revenues evaporated across the travel sector, the rental company had bigger problems, as used car prices collapsed, allowing lenders to call in the money they had lent against its fleet. Almost 50 years earlier, Hertz had moved deftly to turn an economic shock to its advantage. This time, within weeks of the first shutdowns, the world’s biggest car rental company had run out of road.

As part of this series on the New Social Contract, we want to hear what you think should be done to address the social and economic problems exposed by the pandemic. Share your ideas in the comments below and we may publish the best in a follow-up piece. You can also share your thoughts directly with us at coronavirus@ft.com.

Comments