The danger in missing the innovation moment

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Have you ever wondered why hyper-successful companies like Nokia or Kodak suddenly lose their edge? How companies such as Commodore Computers, Grundig, Nakamichi, Newsweek or Polaroid could possibly fail?

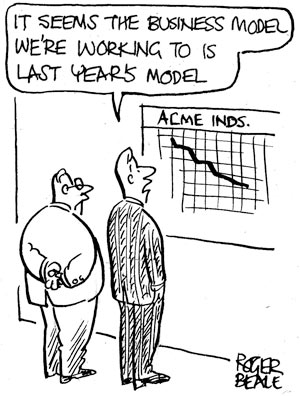

They all had abundant research and development resources, top employees and a profound knowledge of their markets. But they had another thing in common: they all missed the moment when they should have left their successful path to rethink their business models. They missed out on radical innovation because they were too busy managing daily business and serving current clients – instead of looking for future opportunities.

Products and companies do not differentiate winners from losers; it is the right business models that do. Of BCG’s 25 most innovative companies in 2013, 14 are business model innovators. For example, Apple became the biggest music retail seller without selling one CD; Netflix reinvented the video business without operating a single video store. Google continues to attack new industries with its data-based services and devices; Google’s products from glasses, to self-driving cars to smart thermostats are just a means for increasing and leveraging Google’s data-based consumer insights.

Business model innovation is more profitable and more sustainable than product innovation and is badly needed in Europe today.

How are we addressing this issue in business schools? Too often business schools preach interdisciplinary research and team thinking while teaching in functional silos such as strategy, marketing, operations or finance. Global competition requires a more holistic approach to business development that typically reflects business model thinking.

Managers taking a business model view ask who-what-how-why questions for every new product, for every new company and for every new process they develop. Who is our target customer? What are we offering our customer? How do we deliver the value proposition? And why does the business model generate profit? These questions are interdependent and often touch the dominant logic of an industry.

Business model innovators like Google, Amazon, Nestlé, Hilti and Daimler revolutionised their industries by overcoming its dominant logic. Amazon has become the biggest bookseller in the world even though it does not own a single brick-and-mortar store; Skype is the largest telecommunications provider worldwide even though it does not own any network infrastructure.

But overcoming the dominant logic of their industry remains the biggest barrier for experienced managers. Some innovators do it accidentally, some intuitively, but rather seldom as a systematic leadership task.

Compare this to engineering and engineering schools. Every engineer learns design rules for new product development in their first year, but business schools do not teach how to design new business models. Business engineering still seems to be an art that only a few gifted entrepreneurs such as Steve Jobs and Larry Page have mastered.

There are design rules and patterns for business model innovation, but they are rarely actively developed and taught. Developing a business model is a craft that can be learnt.

Research at St Gallen on more than 350 of the largest business model revolutions within the past 50 years found that 90 per cent of all business model innovations are based on 55 core patterns.

For example, when Nestlé invented Nespresso capsules in 1986 it revolutionised the coffee market and today 5bn capsules are sold annually. Nespresso’s strategy of selling its coffee machines for very little, while charging €80 per kg for coffee is based on Gillette’s razor-and-blade business model. Nestlé combined it with a lock-in pattern, where customers cannot switch to competitors’ cheaper products.

Executives, business engineers and innovators have to learn systematically how to develop new business models. Our action research as well as in-house company projects shows that executives can learn these patterns by being confronted with concrete and challenging questions. For example, how would Nespresso run your business? It is amazing how creative managers become once they begin to think in this way.

The biggest challenge is learning how to unlearn. This is a challenge that should be taken up by business schools.

The author is professor of technology management at the University of St Gallen.

Comments