Ukraine: An oligarch brought to heel

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As Moscow annexed Crimea a year ago and pro-Russian separatists started seizing control of town halls across eastern Ukraine, Kiev came up with the novel idea of appointing Ukraine’s richest men as regional governors, in a bid to stop the unrest spreading to the heart of the country. Igor Kolomoisky was the first to sign up.

It was, the billionaire said, a way for the oligarchs “to atone for their guilt before the people by serving the state”.

The policy bore fruit. As governor of Dnipropetrovsk region, Mr Kolomoisky held the line against the Moscow-backed insurgents who now rule large swaths of the east. His financial support for volunteer battalions was critical in blocking the rebels’ advance.

But in Kiev, critics of the oligarch were ringing the alarm. They said he was exploiting his position as governor to expand his business interests, and turning the volunteer units he helped create into his own private army. The fears grew this week after uniformed men apparently loyal to Mr Kolomoisky turned up at the Kiev headquarters of two of Ukraine’s largest energy companies, sparking rumours of a power struggle between the oligarch and Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine’s president.

Suddenly, a week of drama drew to its stunning climax. In the early hours of yesterday morning, it was announced that the president had fired Mr Kolomoisky from his post of governor.

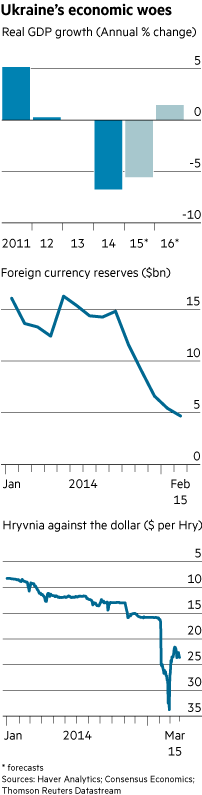

The break between Ukraine’s two most powerful men — once the staunchest of allies — was a political earthquake, and marked the worst internal crisis to engulf the country’s new government since last year’s revolution. It threatens to plunge Ukraine into a fresh round of instability, as it struggles to cope with a debilitating economic crisis and the smouldering insurgency in the east.

The breach also risks playing straight into the hands of the Kremlin, which opposes the pro-western government in Kiev and would rejoice in its collapse.

Yet Mr Kolomoisky’s removal has also drawn praise. “A correct, necessary and decisive act,” tweeted Anders Aslund, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and an expert on Ukraine .

The move was preceded by a series of steps by Mr Poroshenko’s government to clip the oligarch’s wings. This month, parliament passed a law reducing his influence over Ukrnafta, an oil company in which he is a minority shareholder. Meanwhile, the government also sought to impose greater control over Ukrtransnafta, the state-owned oil pipeline operator, removing its chief executive, Oleksandr Lazorko, who was seen as loyal to Mr Kolomoisky.

According to two MPs, Mr Kolomoisky sent a group of men in combat fatigues and ski masks into Ukrtransnafta’s offices late last Thursday to defend Mr Lazorko. After emerging from the building, Mr Kolomoisky told journalists that he and his men had liberated the company from “Russian saboteurs” who had tried to seize control.

Then on Sunday, armed men took up positions around Ukrnafta. Mr Kolomoisky said their purpose was to defend the company against a “raider attack”. The authorities reacted angrily. Arsen Avakov, the interior minister, issued a deadline for the men to be removed, while Mr Poroshenko said no governor should have “his own pocket armed forces”.

Mr Kolomoisky’s dismissal followed.

Tough transition

Witnessing such events, ordinary Ukrainians can be forgiven for feeling disillusioned. Last year’s Euromaidan revolution, which swept President Viktor Yanukovich from power, was supposed to offer the promise of a new Ukraine, free of the cronyism and corruption that have plagued it since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. It was supposed to curb the influence of the small group of tycoons who plundered the country’s wealth over the past two decades and amassed huge political power in the process. Yet recent events show how hard that will be.

“The oligarchic system is still a serious handicap and a brake on the reform process,” says a western diplomat based in Kiev. “If you want to build a new Ukraine, you have to make a break with it.” It is too early to tell whether Mr Kolomoisky’s dismissal represents that break. Cynics in Kiev note that Mr Poroshenko himself is an oligarch, who made a fortune out of chocolate.

Mr Kolomoisky says he is not attached to power and has no political ambitions. In an interview with the Financial Times, given a few days before his dismissal, he said he would leave the post of governor “tomorrow”, “but they won’t let me go”. The reason? “People say [the war] is going to kick off again in the spring,” he says darkly.

A jovial, roly-poly figure dressed in a T-shirt and sporting a bushy grey beard, Mr Kolomoisky is an engaging and often surprisingly candid interviewee. Yet he is also mercurial, switching from twinkly-eyed charm to explosive anger in a heartbeat. He accused one of his interlocutors of “knowing fuck-all”, called parliament a “human rubbish heap” and dismissed his critics as “sell-outs”, “traitors” and “nobodies”.

But, over vodka shots and meat dumplings, he also spoke movingly of his love for Ukraine and the patriotism that inspired him to take on the job of governor. It was this national pride that prompted his famous description of President Vladimir Putin of Russia as a “schizophrenic of short stature”, during last year’s Crimea crisis. Mr Putin shot back by calling him a “unique swindler”.

But Mr Kolomoisky also says he understands why Mr Putin seized Crimea. “He was just taking advantage of the situation,” he joked. “He’s just as much a raider as we are.”

Mr Kolomoisky was born into a Jewish family in Dnipropetrovsk in 1963, when Ukraine was still part of the Soviet Union. From an early age, he showed an entrepreneurial flair: in his 20s he bought rosehips and squash seeds , and traded them in for electrical goods in the village shops: these he then sold at a huge profit in the markets of Dnipropetrovsk and Odessa.

In 1989, visiting relatives from the US brought him a computer, an IBM XT, which he sold to a local factory. “The profit was more than I made from rosehips in an entire month,” he says. He then started travelling to Moscow, buying PCs and selling them to Ukrainian enterprises, and quickly became a rouble millionaire.

In 1992, he and his partners created Privatbank, one of Ukraine’s first private lenders. It is now the country’s largest, accounting for a quarter of all deposits in the national banking system. The Privat Group business empire he set up with his partners has grown to encompass media interests, energy, petrochemicals, aviation and mining as well as banking. His wealth is estimated by Forbes at $1.35bn, but his career has been strewn with spectacular disputes and hostile takeovers which helped cement his reputation as one of Ukraine’s leading corporate raiders.

Business expansion

It is a reputation Mr Kolomoisky at moments seems proud of and at other times rejects, preferring to call his tactics mere “greenmail”. He considers the term “raider” more of a compliment than an insult. Raiders were like wolves, which cleanse the forest by “killing the weak, the sick, for food”. He adds: “If there is raiding, it means the conditions are there to allow it to happen. The law is imperfect. Someone is not managing their property properly. There’s a conflict between shareholders.”

Some of his victims have fought back. Last year, Tatneft, the Russian oil company, won $112m in compensation from Ukraine in an international court of arbitration over the seizure of its shares in Kremenchug, Ukraine’s largest oil refinery, by Privat Group-related structures in 2007.

In the early 2000s, he and his partners started building up a stake in what would be one of their most lucrative investments — Ukrnafta. But his stakeholding has proved controversial. For years, analysts say, the company sold its oil to Privat-controlled traders at below market prices, in monthly auctions that competitors were barred from.

Mr Kolomoisky denies the arrangement was unfair. Oil is not exported from Ukraine, and the country has just one functioning refinery, Kremenchug, which is controlled by Privat Group. “There is only one seller and one buyer on the market,” he says.

Critics dismiss that argument. “I don’t see any benefit to the government and the minority shareholders of Ukrnafta, that together control 55 per cent of the company, of schemes like this,” says Tomas Fiala, chief executive of Dragon Capital and president of the European Business Association in Kiev.

Privat Group effectively controlled Ukrnafta, even though it only had a 42 per cent stake. Ukrainian law stipulated that annual shareholder meetings were only quorate if investors controlling at least 60 per cent + 1 of shares were present. Whenever Naftogaz, the state-owned gas company that owns half of Ukrnafta, tried to change the management or board, Privat would simply not show up to the AGM. The arrangement meant that for years, Privat blocked the payment of dividends worth billions of dollars by Ukrnafta.

The company still owes 1.8bn hryvnia (about $82m) in payouts for 2013. Mr Kolomoisky said he will not distribute them until Naftogaz pays Ukrnafta back for gas he alleges it “stole” from the company and which he says is worth 100bn hryvnia (about $450m).

In recent years, Mr Kolomoisky has lived the life of the post-Soviet oligarch. His main residence is a house on Lake Geneva, he skied every year in the French resort of Courchevel where he says, Russian millionaires pour Château Pétrus on their barbecues, and he owns a $40m superyacht.

That all changed a year ago, when he accepted the call to become governor of Dnipropetrovsk. It was a fateful choice; and it is the reason, he says, why he became so much more powerful than his rival oligarchs. “I was on the side of the Ukrainian state in its darkest hour,” he says. “When the revolution happened, I showed what I was made of.”

The new governor quickly hired private security firms to replace a demoralised police force that had largely disappeared from the streets. He also arranged meetings with all the underworld bosses of Dnipropetrovsk and told them to keep a lid on street crime.

“They all understood, and turned out to be real patriots of Ukraine,” he says.

Mr Kolomoisky clubbed together with local businessmen to supply petrol, diesel and batteries to Ukraine’s army and allowed military helicopters to fill up from his own stocks of fuel in Dnipropetrovsk airport, which he controls.

Meanwhile, he was also helping to mobilise volunteers for the war effort. Some 2,000 men were recruited. He says he only financed the units from March to August last year, and dismisses claims they have become his private army. “I am on the side of order and the state,” he says. “That’s why I’m a governor, and not a field commander.”

Yet there is no denying that Mr Kolomoisky’s connections with the battalions have made him seem more powerful. “Everyone’s afraid of him, including Poroshenko,” says one western businessman.

Regional sway

Over the past year his influence has spread. The region of Odessa in the southeast is now run by one of his close associates, Igor Palitsa, the former boss of Ukrnafta. He also has close ties with the rulers of Kharkiv, a huge region to the northeast of Dnipropetrovsk.

While his star rose, those of other oligarchs faded. Viktor Pinchuk, with whom he is involved in a legal dispute in London’s High Court, is suffering as Russia closes its market to his company’s steel pipes. Dmytro Firtash was arrested in March last year in Austria on suspicion of corruption at the request of US law enforcement agencies: he was later released on bail, but is still in Austria. Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man, who was tainted by his close links to Mr Yanukovich, is lying low in Kiev.

“The age of the oligarchs is over,” Mr Kolomoisky says. “It’s now the era of one oligarch alone.”

Nevertheless, the authorities gradually began to take Mr Kolomoisky on. Earlier in March, the Ukrainian parliament passed a law reducing the quorum needed to call a shareholders’ meeting in any publicly traded company to 50 per cent + 1, from 60 per cent +1 previously. The law could significantly loosen the oligarch’s grip on Ukrnafta.

But, the big move against him only came after his extraordinary show of force on the streets of Kiev in the past few days, which roused the authorities to action. Sergiy Leschenko, an investigative journalist-turned-lawmaker, says the arrival of armoured personnel carriers and automatic weapons on the city’s streets had “looked like the first act of a military coup”.

“[Kolomoisky] placed in doubt the authorities’ monopoly on the use of force — and by remaining in his post he undermined the legitimacy of President Poroshenko and the whole government,” he wrote. “It was a point of no return.”

This piece is now open to comment

Comments