Majors back gas in power switch as a ‘bridge fuel’

Simply sign up to the Renewable energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

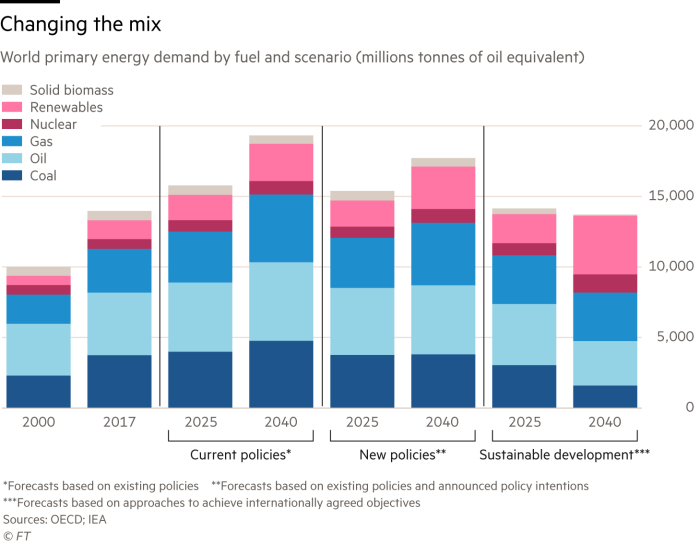

Natural gas is expected to overtake coal as the world’s second-largest energy source after oil by 2030, as more countries seek to curb the air pollution often caused by coal-fired power plants, as demand for electricity ramps up.

The new prediction by the International Energy Agency in its longer-term outlook may justify a push by some of the world’s biggest energy majors to shift their businesses towards gas.

Companies such as Royal Dutch Shell, Total and Repsol are investing more in lower-carbon businesses amid a global transition towards cleaner fuels. They are finding new markets for their gas, such as for power generation.

Gas demand is expected to increase by almost half from today’s levels by 2040, according to the IEA’s new policies scenario, which takes into account current policy ambitions to reduce carbon emissions and fight climate change.

Emerging economies in Asia will account for about half of total worldwide gas demand growth and their share of supercooled liquefied gas imports is expected to double to 60 per cent by 2040, the IEA report said. This is partly because electricity demand in developing countries is increasing rapidly. Electrical power is expected to account for a quarter of all energy used by consumers and industry by 2040.

Even as the share of coal is forecast to fall from about 40 per cent today to a quarter in 2040, renewables will only grow to just over 40 per cent from a quarter now. This means that, despite countries such as India developing renewable power at an aggressive pace, fossil fuels — namely gas — will still be relied on to meet the sheer level of energy demand.

Some energy majors believe a gas shortage is looming as need for the fuel grows, paving the way for an expected wave of new project approvals and expansion targets, particularly targeting the Asian market.

Shell recently approved a $12bn project to send supercooled gas from Canada to China. Qatar, the world’s largest LNG producer, is preparing to expand its facilities by about a third by the mid-2020s.

But others say the future of gas as a less polluting and increasingly popular “bridging fuel” — an essential component in a global transition away from more carbon-intensive energy sources — is not set in stone. Coal demand persists and increasingly affordable renewable power could make gas investments unprofitable.

David Linden, director at consultancy Wood Mackenzie, told a recent conference that a crucial question is what needs to happen for natural gas to “lose out” to better renewables in power generation. This could happen, particularly if batteries improve and storage systems are better able to provide electricity when it is needed, even if the sun does not shine and wind does not blow.

This question hangs over the big spending plans of oil majors, which are branching out into the world of utilities like never before. “These dynamics and questions matter because the rules for how existing and new market participants will be commercially viable are changing. However, the extent of change and the timing is highly uncertain,” Mr Linden adds.

He says solar photovoltaic costs have dropped by 80 per cent since 2010, while mature renewable technologies such as onshore wind have seen a fall of nearly a third. Battery costs, meanwhile, are also down 80 per cent, making storage a more cost-effective solution to renewables’ reliability problems.

Wood Mackenzie says the moment when the world shifts from the age of oil and gas to renewables could occur by 2035, with the adoption of clean power and electrified transport increasing rapidly after this point. At this time, close to 20 per cent of global power needs will be met by solar or wind, displacing the equivalent of about 100bn cubic feet a day of gas demand.

Until then, some energy majors are banking on gas to replace coal in power generation, while others see their role as providing back-up for renewables, particularly as batteries and storage technologies still need to improve greatly.

“All of this is not about a move towards green energy. It’s about a move to an energy system that is cleaner. In a low-carbon world, there is an opportunity to grow into new businesses — including more gas,” says Philippe Sauquet, president of gas, renewables and power at France’s Total.

Given the current trajectory of carbon emissions, fossil fuel companies say a switch to gas is better than no switch at all. Despite global pledges made by governments for the Paris climate agreement in late 2015, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions will continue to grow at a steady pace to 2040. A 10 per cent rise in carbon dioxide emissions from 2017 to 2040 is expected to reach 36 gigatonnes, which the IEA has said is “far out of step” with climate targets.

“Even as energy companies are shifting their businesses towards gas, gas alone is not the only future. Gas as a flexible, low-carbon fuel to back up renewables is key,” says Mr Sauquet.

Comments