Big pharma raises bet on biotech as frontier for growth

Simply sign up to the Pharmaceuticals sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Once biotechs were scrappy insurgents, nipping vainly at the heels of established big pharma. Now the industry’s behemoths are turning to the sector in growing numbers as they seek to replenish their drug pipelines and take a short-cut to high returns.

In the past month alone, several household names have splashed out almost $100bn on businesses scarcely known outside the rarefied circles of Cambridge, Massachusetts and Silicon Valley.

In the dying days of 2018, GlaxoSmithKline announced it was buying Tesaro for $5.1bn; just three days into this year Bristol-Myers Squibb said it would acquire Celgene in an eye-watering $90bn deal and on Monday Eli Lilly announced its intended purchase of Loxo Oncology for $8bn.

Industry leaders meeting in San Francisco this week for the annual JPMorgan healthcare conference have been buzzing with talk of deals done — and, if precedent is any guide, plotting yet more.

This strong appetite has coincided with a drop in biotech stocks, with the MSCI global index falling 12 per cent in dollar terms in the final quarter of last year. Lower valuations for many companies in the sector has made them more attractive to prospective purchasers

Underpinning these acquisitions is a mutually beneficial exchange: the biotechs’ intellectual property in return for big pharma’s scale and reach, and for investors, a potentially large payday.

Steve Elms, managing partner of Aisling Capital, chairman of Loxo and a veteran life sciences investor, noted that the vast majority of new drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, “over the past several years have come from life sciences companies and not large pharmaceutical companies. I would say innovation in biopharmaceutical drug development and discovery has been coming from the biotech industry for quite some time.”

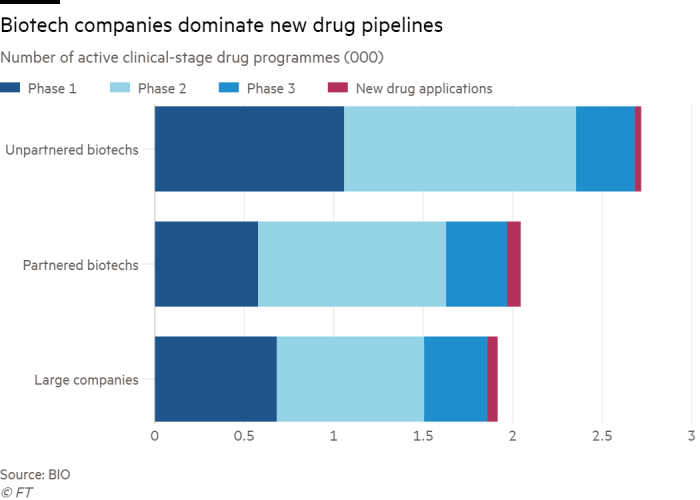

BIO, a global biotech trade association in the US, concluded that 71 per cent of active clinical-stage drug programmes in 2017 involved emerging companies with sales of less than $1bn.

Some of this ferment of activity reflected a highly beneficial investment environment since the end of the financial crisis after the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, decided to add liquidity to the system, Mr Elms suggested.

“That liquidity was looking for high-risk, higher-return assets and Biopharma and biotech companies ended up being the beneficiary of that. So over the past five or six years, you’ve had a huge re-inflation of the cash balance sheets in life sciences companies,” he added.

But a golden era for scientific breakthroughs, particularly in oncology, has also played a part in the sector’s resurgence. Mr Elms cited the success that Loxo, and other biotechs, have had in developing “almost personalised medicines for patients, that are attacking tumours using genomic and genetic information about the mutations and causes of cancer”.

He added: “It’s not like innovation isn’t also going on at pharma, it’s just that life sciences companies, because of their nature, are able to move much faster. They’re able to make decisions faster and therefore get drugs into the clinic and approved much faster.”

Edwin Moses, the former head of Ablynx, which was bought by Sanofi for €3.9bn last year, agrees that culture is one of the things that big pharma is buying, along with promising compounds.

Large pharmaceutical companies “appreciate the innovative culture of biotechs, they understand that biotechs are taking risks in product development which big pharma often wouldn’t even take”.

“That atmosphere is something that pharma like to access when they buy companies . . . and transfuse into the larger organisation,” added Mr Moses, who now chairs two other biotechs, Evox Therapeutics and Achilles Therapeutics.

Another force driving acquisitions may be the increasingly platform-driven nature of drug discovery, as pharma companies look to shore up their position against rivals by rapidly acquiring a key technology.

Novo Nordisk, the Danish drugmaker, initially offered €2.6bn for the company — only for Sanofi to sweep in, fearful of losing access to a platform whose value it had already recognised after working with Ablynx for almost a year.

“The scientists got to know each other very well. They’d seen the technology actually did deliver, so that when the corporate people came to them and said ‘someone’s bidding for Ablynx, should we look at it?’ . . . it [helped] Sanofi come to a very rapid decision,” he said.

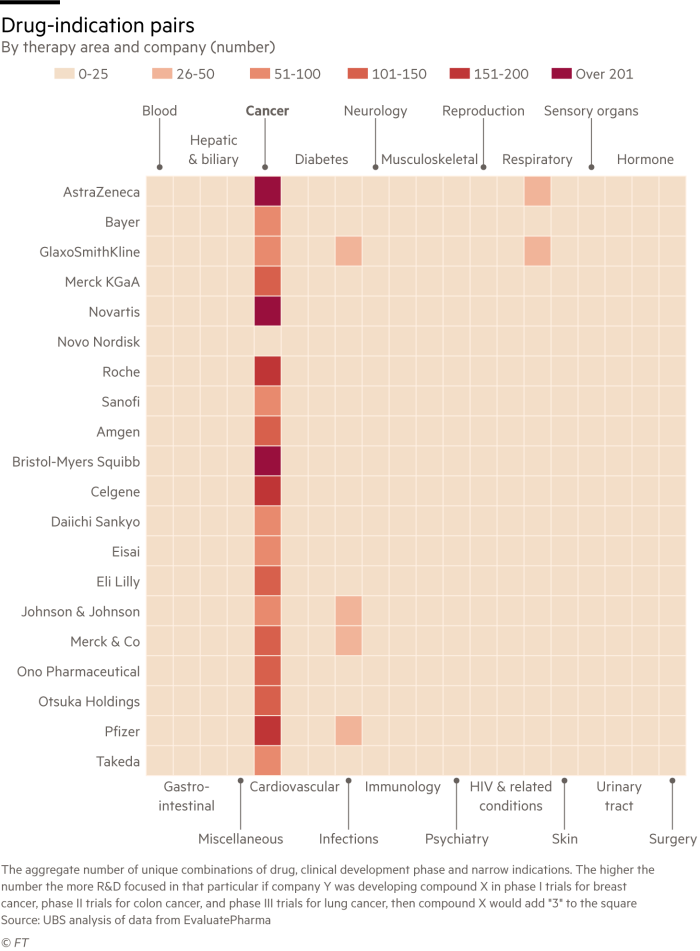

Judging by recent deals, not just biotechs, but specifically cancer treatments, are high on acquisition-minded CEOs’ wishlists.

Jack Scannell, an analyst at UBS, said the growth in combination cancer treatments, that involve two different compounds, lends itself to big pharma-biotech collaborations and “to a certain extent explains the rash of oncology M&A”.

“If you’re Roche or Astra or Bristol or Merck, you have compounds of many different classes in your pipeline . . . you can run these early trials where you basically try lots and lots of combinations within the same legal and administrative clinical trial structure”, with any successes then commercialised via big pharma’s sales forces.

This kind of clinical development, he suggested, “is too complicated [and] impossible for small standalone companies . . . big companies are the natural home at the moment of clinical stage oncology assets”.

Not all big pharma/biotech deals work smoothly. Just last week US drugmaker AbbVie announced roughly $4bn in impairment charges related to its decision to scrap development of Rova-T, an investigational cancer therapy acquired after it bought Stemcentrx in 2016, as part of a strategy to deepen its investment in oncology.

However, despite this demonstration of what can transpire when a company is acquired before a key medicine has proven its worth, 2019 seems certain to see big pharma continuing its biotech tear. Speaking at JPMorgan this week, Emma Walmsley, chief executive of GSK, indicated she, for one, is far from being done with dealmaking, saying she would look to buy early-stage assets and partner with companies.

Steve Bates, who heads the UK’s BioIndustry Association, agrees that “we will see more of [these deals]”. The reason, he said, is that “big pharma have strategically decided . . . that they’re not going to get their next generation products from in-house cathedrals of R&D”.

“If the majority of their pipeline is going to come from external companies, then drug discovery and drug development are going to come from the biotech ecosystem, increasingly — and they’re going to have to pay for [it].”

Talent exchange

The recent flurry of dealmaking is not the only sign that the boundary between large pharmaceutical companies and the biotechnology sector is becoming increasingly porous. A number of senior executives from major drugmakers have been jumping ship to biotechs, as big pharma’s smaller cousins prove they have the clout to lure big name talent.

Daniel O’Day, head of pharma for Roche and one of the industry’s most high profile figures, announced last month that he was leaving the Swiss drugmaker to take the helm at Gilead Sciences. Mark Mallon, who held a number of senior executive positions in 24 years at AstraZeneca, will become chief executive of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals which specialises in gastro-intestinal treatments.

Meanwhile, after six years as president of AstraZeneca subsidiary MedImmune, Bahija Jallal was this month appointed chief executive of Immunocore which develops biological drugs to treat cancer, infectious diseases and autoimmune diseases. Just this week, the latest biotech signing was announced: Roche executive Pearl Huang’s move to lead Cygnal.

Steve Bates, chief executive of the BioIndustry Association, which represents biotechs in the UK, said such swaps had “happened successfully and unsuccessfully through history. Sometimes the culture change has been too significantly different and [it] hasn’t worked”.

But he added: “What you’re now seeing is that some of the pharma players who have worked in R&D do see the opportunity of building companies that might be acquirable. They can see the faster pace in which they can do that, and potentially a bigger opportunity in terms of personal reward, and they’re prepared to take that risk.”

Comments