How traders trumped Quakers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To the thoughtful observer, it has as much in common with historic regiments, religious cults, primitive tribes and small countries as it does with its rivals along the British high street.

So said Martin Vander Weyer in his colourful account of the chequered, late-20th century history of Barclays. But today, after a torrid year and a half under the hard-driving stewardship of former Wall Street trader Bob Diamond, and the rigging scandal surrounding the London interbank offered rate that this week led to his departure, it all looks very different.

The sober values of the Barclays, Bevans, Gurneys, Tukes, Trittons, Thomsons and other Quaker families that helped turn it into a great national institution over 300 or so years now seem remote, after a momentous fortnight in which the US and UK authorities fined the bank £290m for manipulating the Libor rate and chairman Marcus Agius resigned – then felt obliged to return, in the wake of Mr Diamond’s dramatic exit. The scandal has also rocked the share price and injected heat into the debate about the state of banking and its regulation.

So what went wrong with the culture of this once venerable enterprise?

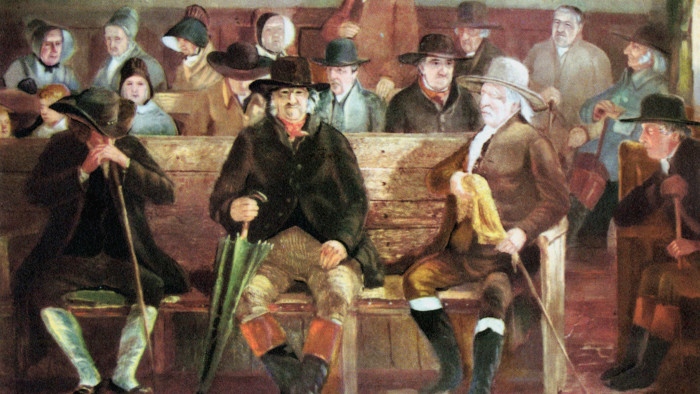

In one sense, Mr Diamond has more in common with his Quaker predecessors than it might first appear. Back in the 17th century, members of this nonconformist denomination were treated as renegades by the political establishment – something about which Mr Diamond knows a thing or two. The strong Quaker presence in banking stemmed from their exclusion from professions such as the law and, because of their pacifism, the army. They derived a competitive edge from their reputation for integrity and mutual trust.

By the time of Barclays’ heyday in the mid-20th century, descendants of the founding families remained in charge despite having only a minimal equity interest in the bank, and some of that culture remained. In the assistant managers’ lunch room, says Mr Vander Weyer, the meal was still preceded by grace.

Yet the families were no longer outsiders, and a peculiar feature of the organisation was the rigidity of class distinction bordering on apartheid. Talented bankers were excluded from promotion to the top, including Deryk Vander Weyer (father of Martin), whose bid for the chairmanship was quashed in 1980. Sir Brian Pearse, a Barclays finance director who became chief executive of Midland Bank, famously remarked: “They just didn’t have the balls to make him chairman and the whole bank resented it.”

In many ways the bank resembled a club and, as so often with British clubs, the thing worked surprisingly well despite its flaws. The founding families helped by steering only their more talented children into Barclays. And the lower orders gave of their best, notwithstanding. It was, in fact, the most innovative of the British clearing banks in the postwar period. In 1967 it installed the world’s first automated cash teller machine, an idea dreamt up in the bath by John Shepherd-Barron of De La Rue Instruments that was seized upon by another great general manager, Derek Wilde. Barclays also came up with the first plastic payment device, Barclaycard, still outstandingly successful.

By the 1980s, though, the talent was becoming thinner as disillusioned meritocrats departed and the strategic challenges became greater, with more intense global competition. In 1986, a turning point in Barclays’ history, it was overtaken by National Westminster in terms of profitability and faced Big Bang, which liberalised the London Stock Exchange, bringing the City closer to US trading practices.

The board’s response to the NatWest challenge was not driven by concern for shareholder value. It supported a disastrous dash for growth, which ended with punishing write-offs against property lending in the early 1990s after two rights issues that made Barclays very unpopular with institutional investors.

With Big Bang, its answer, masterminded by Lord Camoys, managing director of Barclays Merchant Bank, was to buy two of London’s best known securities houses, Wedd Durlacher Mordaunt and de Zoete & Bevan. The aim was to create an equities business as part of an integrated investment bank along American lines, to be known as Barclays de Zoete Wedd (BZW).

Barclays’ origins: A paragon of probity whose successors proved too recklessVisitors pouring towards London’s Olympic Park this summer are unlikely to notice the unobtrusive granite obelisk that stands a few hundred metres away, on the corner of Stratford’s main thoroughfare.

Yet it commemorates a man now being held up as a model of probity and philanthropic spirit, to contrast with the recent excesses and malpractice tarnishing the UK banking sector and the culture of the City.

Samuel Gurney, once known as the “bankers’ banker”, exemplified the values of the Quaker banking dynasties in which Barclays has its roots. From 1809, he headed the Gurney family’s Norwich-based bank, which thrived through successive banking crises, attracting depositors who had lost faith in shakier London institutions.

While his sister, Elizabeth Fry, won prominence (and a place on the current £5 note) for her work on prison reform, his charitable endeavours ranged from donations to alleviate the Irish famine, to a new hospital for dock workers, to abolitionist campaigning that resulted in a town named after him in Liberia.

Yet he also built the business that later became the first real test of the Bank of England’s willingness to let a systemically important bank fail. Under his management, Overend, Gurney & Co became easily the largest of the bill broking companies that then performed similar functions to today’s money market funds, accepting bills from other institutions to reinvest in British trade and manufacturing.

After his death, however, Overend Gurney fell under more reckless managers, who were seduced by the temptations of Victorian Britain’s boom years. It owned lossmaking commercial fleets in the Mediterranean; made bad investments in railroads – the speculative bubble of the age – and in May, 1866, was forced to seek a £400,000 bailout from the BoE. The BoE refused, prompting a market panic and runs on the Gurney family’s retail banks, showing a rigour on matters of moral hazard that bears comparison with its stance more than a century later, when it faced the country’s next bank run – on Northern Rock.

Walter Bagehot, then the Economist’s editor, wrote Overend Gurney’s losses had been “made in a manner so reckless and so foolish that one would think a child who had lent money in the City of London would have lent it better.”

Most of the family’s regional retail banks failed, but the original Norwich bank was saved in a rescue staged by the city’s notables – and went on to merge with other Quaker banks in 1896 to form what is now Barclays.

Delphine StraussLike the other clearers – and indeed big US commercial banks such as Citigroup, Security Pacific and Chase Manhattan, all of which bought and, to critics, grotesquely mismanaged other City brokers – Barclays had great difficulty combining conventional and investment banking in a coherent model.

The chief problem was culture. As Michael Lewis, author of Liar’s Poker, a commentary on Wall Street in the 1980s, memorably put it, a commercial banker was someone who had a wife, a station wagon, 2.2 children and a dog that brought him his slippers when he returned home from work at 6pm. An investment banker, by contrast, was “a breed apart, a member of a master race of dealmakers. He possessed vast, almost unimaginable talent and ambition. If he had a dog it snarled. He had two little red sports cars yet wanted four. To get them, he was, for a man in a suit, surprisingly willing to cause trouble.”

The battleground between conventional bankers and investment bankers usually concerned pay and resources. Philip Augar, who ran NatWest’s global equities business between 1992 and 1995, points out that the bonus round in an investment bank is the most important time of year. Get it wrong and the business unravels; pay too much and profitability is shot to ribbons.

In a universal institution, the retail and commercial bankers often, maybe always, feel that too many of the investment profits are being paid to staff and inevitably resent the fact that investment bankers’ bonuses are bigger than their own. For their part, the investment bankers always fear that the management wants to build the investment side on the cheap.

…

Certainly that was the pattern of the trench warfare at BZW. In 1994 a dearth of in-house talent led to the appointment of Martin Taylor, a former Financial Times journalist who had been chairman of Courtaulds Textiles, as chief executive. While acknowledging that much had been done to build the business from a lowly base, he found BZW underperforming in an overcrowded market. Most of the money was made by the Barclays treasury department. So he decided to bring in a new chief executive, Bill Harrison of investment bank Robert Fleming, to create impetus. Also recruited was a trader called Bob Diamond, who had previously been vice-chairman in charge of fixed income and foreign exchange at CS First Boston in New York – in an interesting warning – he resigned in disgust over his 1995 bonus, which press reports put at $8m.

Yet within a short time Mr Taylor concluded the numbers would never stack up. He presented a paper to the board in 1997 arguing that Barclays risked lacking sufficient scale across all its businesses, and that it would be better to abandon investment banking. As in the late 1980s, the board decided Barclays ought to be in the big league regardless and rejected the proposal. Investors then grew restive as BZW absorbed more capital while generating lower returns. The board finally accepted that the cost of staying in the global race was too great, and sanctioned the sale of the equities and corporate finance businesses.

By this time another cultural shift had taken place in investment banking. As trading profits in securities and derivatives rose inexorably in buoyant markets, the power of the traders rose in their organisations at the expense of more staid corporate financiers. The individualistic, bonus-driven ethos of the trading floor permeated institutions in which the idea of fiduciary obligation to customers was ebbing away. Traders came out on top both in the US and in Europe, where Anshu Jain, the new co-chief executive of Deutsche Bank, Brady Dougan of Credit Suisse and Stephen Hester of Royal Bank of Scotland all come from a trading background.

It was surprising, then, that Mr Diamond did not find his way on to the Barclays board before 2005. He became chief executive at the start of 2011, having conspicuously succeeded in building up the fixed interest business at the Barclays Capital subsidiary. And he achieved what many in London saw as the holy grail – a powerful position on Wall Street – with an opportunistic grab for Lehman Brothers’ US business after its collapse in 2008. This was a daring move, especially when Barclays itself had come within a whisker of falling into state hands before raising equity from Qatar when the financial crisis was at its most dangerous.

…

Yet there were tell-tale signs of reputational trouble ahead, and not just from the constant public controversy over Mr Diamond’s pay or the probe into Libor rigging, stretching back to 2005. The bank’s traders have also been under investigation for allegedly manipulating Californian electricity prices. A Canadian court last year accused Barclays of making fraudulent misrepresentations in its dealings there. Its financing of tax avoidance schemes was deemed highly abusive by UK authorities. And the retail bank’s culture has been put in question by the cynical mis-selling of payment protection insurance. The credibility of Barclays’ aspiration to good corporate citizenship, to which the annual report gives high prominence, is in tatters.

These problems are common to banking on both sides of the Atlantic. Nor is Barclays alone in its exposure to the Libor scandal. But there remains a question as to Mr Diamond’s legacy. While his achievement in the fixed interest business has been considerable, it occurred against the background of one of the longest bond bull markets in history. With interest rates approaching historic low points, this may now be close to an end.

The business model is also under challenge from the proposals of the Vickers commission’s review of UK banking for separating retail from investment banking within big financial institutions. If the ringfencing is effective, Barclays’ investment bank will lose its implicit state subsidy, which will put it at a big competitive disadvantage to American and continental European universal banks.

That brings Mr Taylor’s concerns about Barclays lack of scale back into the picture. A further question, raised by Mr Diamond’s declared ignorance of what his bank was doing in its reporting on Libor, is whether this behemoth is too big to be managed.

Bartlett Gurney, an 18th century member of one of the Barclays founding families, had a pithy take on this. “A little business with a little profit and an entire regularity,” he said, “is happiness sterling to the true merchant; while a large business, expecting large profits, but in confusion and disorder, may be flattering but creates much anxiety and little comfort.”

That could apply equally to the whole British banking system, which is uncomfortably large in relation to gross domestic product. Those Quaker bankers may still have something to teach us all.

Comments