Science v poachers: how tech is transforming wildlife conservation

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is dry season in a Kenyan national park. A small group of poachers walks along a dried-up riverbed, aiming to kill a black rhino and remove its horns, which could fetch as much as $100,000 on the Asian black market.

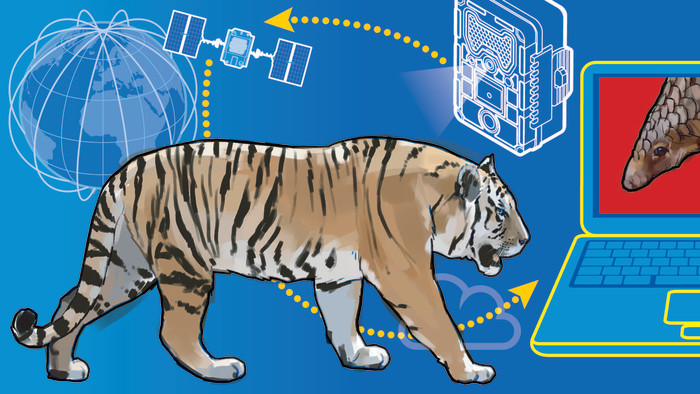

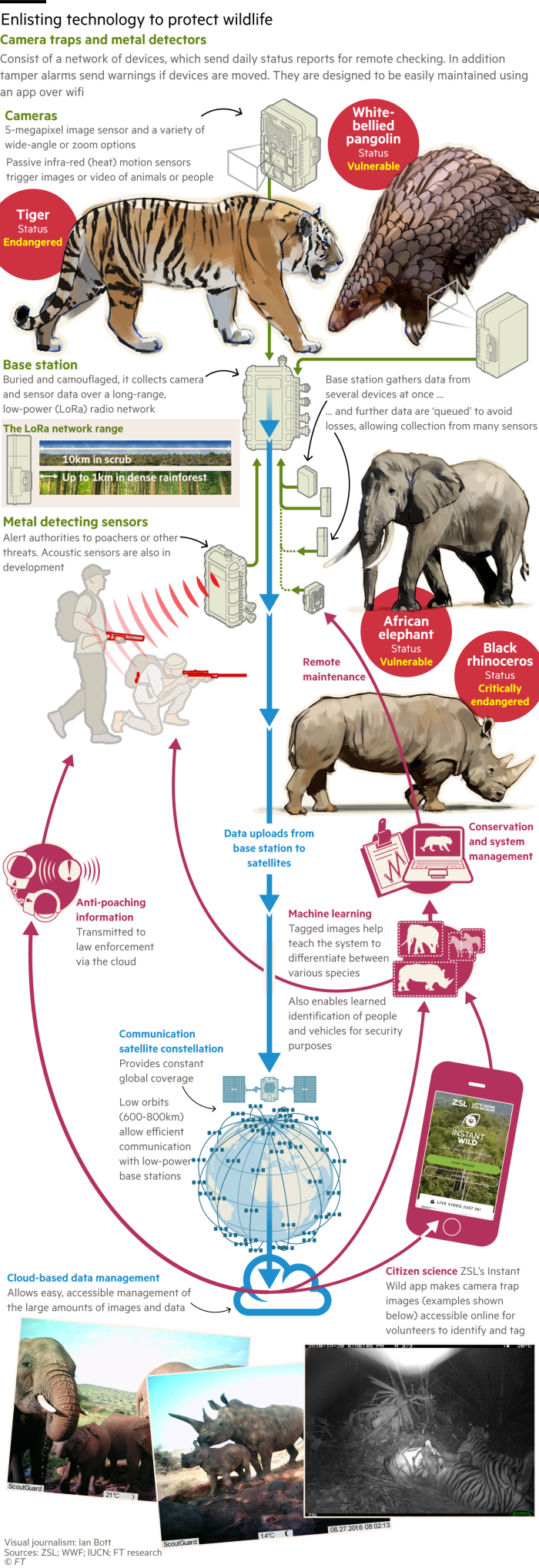

The men are concealed by undergrowth on the riverbanks but seen by a poaching alarm system developed by the Zoological Society of London. Their guns and knives trigger the Instant Detect system’s hidden metal detector, which activates a camera camouflaged in a bush. The images travel by radio to a base station and then via a communications satellite to the park headquarters, alerting the authorities in time to dispatch rangers and catch the gang.

Similar scenarios will soon be playing out in reserves and parks around the globe, as conservation bodies adopt a high-tech approach in their battle to protect animals. Some of these groups were slow to see the potential for new monitoring tools, but with the aid of groups such as Google they are now embracing the devices as a way to tackle poaching.

WWF estimates the illegal wildlife trade is worth about $20bn a year and has contributed to a catastrophic decline in some species. According to the Living Planet Index maintained by WWF and ZSL, the FT’s Seasonal Appeal partner for 2019-20, 60 per cent fewer vertebrate animals (mammals, bird, reptiles, amphibians and fish) live wild now than 50 years ago, with the steepest drops in the tropics.

Although huge falls in populations of some well-known species such as tigers, elephants and black rhinos have been halted and even reversed through intensive conservation efforts, poachers are still killing them — while numbers of other animals, including pangolins and many monkeys, are declining fast.

There are many drivers behind the loss of biodiversity, from overfishing and climate change to urbanisation and local pollution. But for some species illegal trapping and killing is the biggest factor in their decline, says Andrew Terry, head of conservation at ZSL.

“We have a particular focus on tackling the international wildlife trade but that is embedded in our broader conservation efforts,” says Mr Terry.

Zoologists have used camera traps to photograph passing animals for decades but until recently these had no wireless connection, so their operators had to physically visit each one to remove its film and later its electronic SD card, which was often full of useless images of moving branches or other wildlife that had triggered the trap.

“The odd thing is that conservationists were slow to take up technology,” says Eric Dinerstein, director of wildlife and biodiversity at Resolve, a conservation charity based in Washington DC. “We jumped in around six years ago because we saw an opportunity to make a difference with a camera trap with intelligence and connectivity.”

Other conservation bodies including ZSL began to develop detection technology at about the same time, working with tech companies that see wildlife protection as a showcase for their expertise. Systems such as ZSL’s Instant Detect and Resolve’s TrailGuard are in the final stages of testing and will be soon ready for deployment in the field.

“Conservation organisations don’t generally have the resources to recruit and employ expensive software engineers and developers, so we depend on collaboration with the tech industry,” says Sam Seccombe, Instant Detect project manager. ZSL’s partners include Google and Iridium, the satellite communications operator, while Resolve is working with Intel, Microsoft and Inmarsat, another satellite company.

Google’s AutoML system, which enables people with limited expertise to develop artificial intelligence for specific purposes such as image recognition, is being deployed in Instant Detect, making it possible to recognise people or animals instantly from camera trap pictures.

“A successful business relies on being able to collect, analyse and interpret data rapidly to make the best business decisions,” Mr Seccombe says. “The same is true for conservationists using camera trap data. By increasing the speed of image analysis, conservation impact can be made more quickly and be more effective.”

Remote wildlife parks have little or no mobile phone coverage, so Instant Detect uses its own radio transmitters to send images to a buried base station and then on by satellite to headquarters. ZSL tested the first version of the system by monitoring Antarctic penguins, Canadian bears, Australian night parrots and Kenyan elephants and rhinos. But it suffered from transmission problems, particularly in dense foliage.

The team has developed a more robust and reliable second version, Instant Detect 2.0, which has had successful preliminary tests in Africa and will undergo more extensive trials in the new year in Thailand’s Western Forest Complex and elsewhere before operational deployment.

Camera quality was also an issue. Nothing on the market met ZSL’s specifications so it developed its own 5-megapixel Instant Detect camera with a wide range of focal lengths, triggered either by an inbuilt infrared sensor that detects heat and motion of a passing animal, or by an external metal detector for poachers. “It seems ironic that most trail cameras being used by conservationists have been designed for the deer hunting market,” says Mr Seccombe.

Although the camera has a powerful computer chip that could run an automatic image processing system on captured pictures to decide whether they are worth transmitting, this feature will not be used initially, so as not to overload the system. Instead, image processing will take place in the cloud after the images have been transmitted.

Another development in the near future will be the integration of acoustic sensors, triggered by sounds such as a gunshot, chainsaw, engine or animal call. ZSL is developing a machine-learning algorithm to detect shots in collaboration with Google.

Resolve’s TrailGuard, which incorporates Intel vision-processing chips in its cameras, does carry out AI image analysis locally, so that only pictures of human intruders are transmitted — extending battery life and cutting transmission costs. The first version of TrailGuard, operating in the Grumeti reserve in Tanzania last year, detected more than 50 intruders and enabled rangers to make 30 arrests from 20 different poaching gangs and seize 1,000kg of illegal bushmeat.

Mr Dinerstein says Resolve is manufacturing 1,000 updated TrailGuard units, 300 in California and 700 in China, for installation in parks in Africa and elsewhere. The US foundation proposes to protect 100 wildlife parks and reserves over the next two years, by placing TrailGuards on the 10 trails used most actively by poachers in each place. Once satellite modems have been installed, the number of cameras can be increased to as many as 100 per park.

Installation would cost a park an estimated $17,000 in the first year and slightly more in the second year, with future operating expenses for data transmission at about $200 a year — much less than alternative protection measures such as flying drones to spot poachers or employing additional rangers.

Anthony Dancer, who manages ZSL’s tech programme, warns that new technology cannot stop illegal killing on its own. “Most protected sites around the world are terribly underfunded,” he says. “Even if we make the technology available, many places will not have enough resources to manage the technology or enough rangers for a large increase in enforcement.”

Besides poaching for meat, horns, teeth, scales, fur and other valuable products, people also kill animals to stop them raiding crops or livestock. Resolve plans to tackle this growing conservation problem by adapting its TrailGuard hardware to identify animals rather than people, for a project called VillageGuard.

Camera traps, installed along trails used by large animals that eat or trample crops or attack livestock, will automatically detect intruders. The first five targets are elephants and lions in Africa, snow leopards and wolves in Nepal, and grizzly bears in the US. Attached speakers will then frighten away the unwanted animals with alarming sounds such as human shouting.

Beyond the detection of threats to wildlife from poachers or angry villagers, conservation bodies are enlisting information technology to track elusive animals. They analyse the rapidly increasing volume of images emerging from camera traps installed around the world. ZSL uses both machine learning and human volunteers for this task.

Several projects are under way to identify animals through AI. The largest collaborative programme, called Wildlife Insights, sits in Google Cloud and combines the company’s machine learning expertise with a group of conservation groups including ZSL. It has been trained to recognise 614 different species with 8.7m images supplied by member organisations — and expects to expand rapidly as conservationists feed in more data. Initial accuracy ranges from 80 per cent to 98 per cent, depending on the quality of the image and the distinctiveness of the species.

“Wildlife Insights is essentially a massive open source system that will enable people around the world to manage and analyse biodiversity data,” says Mr Dancer.

While artificial intelligence becomes an ever more powerful tool, humans will always play an essential role in wildlife identification — including amateur as well as expert zoologists. Instant Wild is ZSL’s free citizen science app that anyone with a smartphone can use to identify animals in camera images; it has been downloaded 130,000 times. Crowdsourcing analysis of this sort is useful for educating and involving the public, as well as directly assisting with species identification.

“You don’t need to be an expert. You just give your best guess,” says ZSL project manager Kate Moses. “The result only goes through to the project scientist when 10 people have given the same identification.”

Technology is also helping the people on the front line of the battle to protect wildlife: the 300,000-400,000 rangers and wardens who work in the world’s parks and reserves, according to the International Ranger Federation. A system called Smart (for Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tool), developed by ZSL and other conservation bodies, enables rangers to collect and sort out data on their mobile devices about the locations of animals and humans, including illegal intruders, in order to deploy scarce staff as efficiently as possible.

Smart is already being used in 900 protected areas around the world. AI software developed by Harvard computer science professor Milind Tambe will be integrated into the system next year. This predicts poachers’ behaviour, so that patrols can be directed to likely hotspots of illegal activity.

With animal populations under enormous pressure, technology has huge potential for enabling conservation groups to deploy their resources more efficiently in the battle against poaching and the wider illegal wildlife trade.

“We urgently need to innovate, and to create new partnerships with industry, governments and academia, to develop new solutions,” says Mr Dancer of ZSL. “This is where technology and tech partnerships have the potential to be transformational — by enabling us to target our resources more efficiently and more effectively, and to scale our impact.”

Tracking the trade: forensic approach helps crackdown on trafficking

The primary aim of conservationists is to stop poachers killing animals but, when they fail, advances in forensic science can help to catch criminals in the illegal wildlife trade.

Researchers are enhancing fingerprinting technology to improve the chances of obtaining clear prints from people who have handled animal parts.

Working with colleagues at the University of Portsmouth, ZSL scientists are using “gel lifters” — small sheets coated with sticky gelatin — to remove fingerprints from pangolin scales and other unpromising materials such as snake skins. The prints are then read with specialist imaging machines .

Another collaboration, involving City of London police and King’s College London, has developed a new magnetic powder that enables investigators to recover human fingerprints from elephant tusks with much better definition than conventional methods. It can recover prints up to four weeks old, giving more time to gather evidence on criminals who have handled ivory seized by police or customs officers.

Conservationists are also using new genetic analysis in two ways to investigate wildlife crime. First, if poachers leave tiny traces of their DNA on ivory, horn or other material, it may be possible to track them down through a genetic fingerprint.

Second, animal DNA extracted from illegally traded materials can be used to trace its geographical origin. This prospect may be particularly applicable to smuggled ivory, as scientists build up a database showing the genetic differences between elephant populations in different parts of Africa.

Scientists at Liverpool John Moores University have used ultrasensitive DNA probes to help spot illegal animal material within large cargo consignments at borders, ports and customs posts. In a proof of concept study published this month they rapidly identified tiny quantities of tiger, rhinoceros and pangolin DNA.

How you can help

Please help us support ZSL’s urgent work by making a donation to the FT’s Seasonal Appeal. Click here to donate now.

If you are a UK resident and you donate before December 31, the amount you give will be matched by the UK government — up to £2m. This fund-matching will be used to help communities in Nepal and Kenya build sustainable livelihoods, escape poverty and protect their wildlife.

Read more about our Seasonal Appeal partner ZSL: ft.com/zsl-facts

Comments