Pharmaceuticals: Brain power

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Garbed in white lab coat and goggles, a young scientist carefully cuts a mouse’s brain into wafer thin slices. She adds a drop of dye to each one before placing it under a slide for inspection beneath a microscope. On a nearby computer screen is a close-up image of a brain fragment from a second mouse, stained with what a researcher says are the telltale signs of a plaque associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

The location is Eli Lilly’s neuroscience research centre in the leafy Surrey commuter belt west of London — part of the front line in the battle against dementia: a condition that affects tens of millions worldwide and weighs heavily on health budgets. Until recently, it looked like a fight that was being lost as one clinical trial after another ended in failure. But in recent months, there have been tentative signs that the tide could finally be turning in the search for an effective treatment.

This new sense of optimism is expected to be underscored this week at the annual Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Washington. As well as researchers and medics, investors will be there in force as Wall Street eyes the multibillion-dollar market opportunity awaiting any company that can deliver a successful drug.

Hopes of a breakthrough have been rising since March when Biogen, the US biotech group, announced positive trial results for an experimental Alzheimer’s medicine called, aducanumab. Sceptics cautioned that it was too soon to get excited about what was an early-stage study involving just 166 patients. But the bullish mood will become harder to resist if, as widely expected, Eli Lilly provides further cause for encouragement when it reveals data from a much bigger trial of its solanezumab drug in Washington on Wednesday.

“We’ve been chasing this goal for 26 years,” says Trafford Clarke, managing director of the US group’s Surrey research centre. “Other companies would have shut this down a long time ago but we’ve carried on because we believe it can work.”

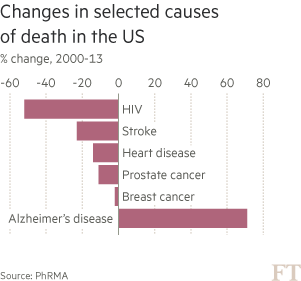

Worsening epidemic

Of all the health challenges being tackled by the pharmaceuticals industry, few are more difficult and pressing than dementia — a term which describes a range of memory-wasting conditions of which Alzheimer’s is the most common. Alzheimer’s alone is the sixth most common cause of death in the US, and the only disease among them without a treatment capable of slowing it. As medical breakthroughs improve the chance of surviving other big killers such as cancer and heart disease, ever more people are falling into dementia’s cruel grip. Yet, for all the recent optimism, the condition remains poorly understood.

“The brain is the most complex 1.5kg in the universe so when it goes wrong, trying to fix it is extremely difficult,” says Eric Karran, who has held senior neuroscience roles at Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Pfizer. “In oncology, you are trying to kill cells; in neurology you are trying to keep cells alive. It’s a lot easier to do the former than the latter.”

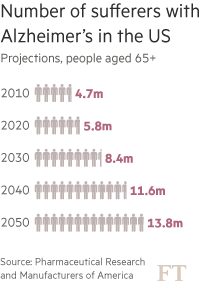

The number of people living with Alzheimer’s worldwide is forecast to rise from 44m today to 76m — almost equal to the combined populations of France and Belgium — by 2030, according to Alzheimer’s Disease International, an advocacy group. Ageing populations from the US to China are driving up the number of sufferers.

The worsening epidemic threatens not only a public health crisis but also an economic one. A quarter of UK hospital beds are already occupied by patients suffering from some form of dementia and the cost of these conditions is forecast to soar from £23.6bn last year to £59.4bn by 2050, according to the Office of Health Economics. The potential of an effective drug to reduce expensive hospitalisation and residential care means that policymakers are as eager as patients for the industry to succeed.

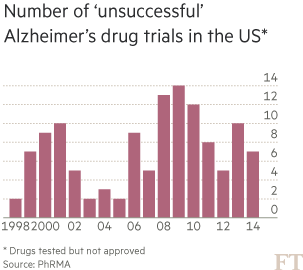

Yet, for a long time, Eli Lilly received little credit from investors for its dogged pursuit of Alzheimer’s. The disease had become known as a scientific and financial black hole into which the industry had thrown away billions of dollars. Between 1998 and 2014, there were more than 120 failed Alzheimer’s trials and just four new medicines reached market. These rare successes have offered temporary symptomatic relief to patients — typically for six to 12 months — but do nothing to slow the advance of the disease.

Dr Karran, now head of research at the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK, recalls the internal debates within companies where he worked, weighing the huge potential rewards from a successful drug versus the equally big risks. “If you have a failed Alzheimer’s drug in a late-stage trial that’s $400m down the tube,” he says. “You might have brought three new life-saving cancer therapies through for that money so there is an ethical as well as a financial dimension.”

Several companies including Pfizer largely abandoned Alzheimer’s after failed trials and many observers thought Eli Lilly would do the same when solanezumab failed to slow the rate of cognitive decline in a large, late-stage trial three years ago. But researchers saw a silver lining in the disappointing data: a 34 per cent slowing in the rate of mental decline among those suffering from mild, early-stage Alzheimer’s. This suggested the drug might work if administered before the disease became too entrenched.

Modifying the disease

Trial participants with mild symptoms were allowed to continue taking the drug for a further two years and it is data from this extension period that will be revealed on Wednesday. Patients who had been taking a placebo during the initial trial were switched to solanezumab for the extension period. If the drug is truly “disease-modifying” rather than a temporary palliative, people who were taking solanezumab from the beginning should maintain a cognitive advantage over those who started later.

Scientific quest

A fight to find the answer to dementia puzzle

Scientists have been investigating the connection between Alzheimer’s disease and sticky clumps of protein called beta-amyloid since the 1980s.

The presence of this plaque in the brains of people with the disease is believed to contribute to the destruction of nerve cells in ways that gradually impair mental functioning.

Drugmakers such as Eli Lilly, Biogen and Merck are betting on there being a causal effect as they press ahead with treatments aiming to clear the plaque or inhibit its production.

Roger Perlmutter, head of research and development at Merck, likens the pursuit of these drugs to the drive to lower cholesterol levels in those at risk of heart disease. “We had no idea whether or not lowering cholesterol

. . . would actually improve outcomes. We now know it does.”

Yet beta-amyloid is not the only anti-Alzheimer’s game in town. Some scientists think the presence of tangled fibres made of a protein called tau may be at least as important and several drugs are in development targeting it.

Advocates of the “amyloid hypothesis” and the “tau theory” are often portrayed as warring camps but Doug Brown, research director at the UK’s Alzheimer’s Society, says both have a role but “it remains to be seen which is the better target for drugs”.

Some early-stage studies are focused on the immune system, with evidence suggesting that inflammation in response to nerve cell death may be another factor in the disease.

Scientists say a combination of approaches is likely to prove most effective in the long run. Ben Newton, who heads a neurological imaging business at GE Healthcare, predicts that increased understanding of the disease will simply reveal further complexity. “A few decades ago there was just one condition called leukaemia,” he says. “Now we know there are at least 60 types. We will see the same thing with dementia.”

Eli Lilly has already disclosed that just such a gap was maintained in the first six months of the extension and investors are hoping it will declare this week that the differential was maintained over the full two years.

Derek Hill, chief executive of Ixico, a UK company that provides clinical trial and imaging services for Alzheimer’s research, cautions against hope of miracle cures. “Success is not going to be defined by taking someone in residential care, giving them a drug and taking them home; that’s not going to happen. The aim is to slow down the progression of the disease so people can remain independent for longer.”

If the Eli Lilly data are positive it would mark the second validation this year of the “amyloid hypothesis” — which identifies the build up of beta-amyloid plaque as a cause or contributing factor behind Alzheimer’s. Both solanezumab and aducanumab aim to clear this plaque from the brain. Biogen’s data in March showed a statistically significant reduction in beta-amyloid as well as a slowdown in the pace of mental decline among patients.

“It is a long time since we’ve seen positive results of this type,” says Thomas Wisniewski, neurology professor at New York University’s School of Medicine, who recalls an “ecstatic” reaction in the audience when the data were announced at a medical conference in Nice, France.

Concerns over side effects from the Biogen drug have since curbed some of this enthusiasm. But the results were encouraging enough for Roche to take another look at data from a failed trial of a similar drug in the hope of reviving it.

“Many of the drugs that have failed would have very likely succeeded if the trials had been better targeted,” argues Dr Karran, highlighting the uncertainty that often exists over whether a patient has Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. Attempting to learn from past mistakes, Eli Lilly launched an entirely new solanezumab trial in 2013 involving 2,100 patients who were more thoroughly screened to make sure they had the greatest chance of benefiting.

John Lechleiter, chief executive of Eli Lilly, told the Financial Times earlier this year that a “reasonably significant portion” of participants in the previous trial turned out to have been given a false diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

The company has focused part of its latest trial on people whose brains have begun to show signs of amyloid build-up but whose cognitive ability remains normal. “It’s clear that plaques form, in some cases, long before symptoms are seen,” added Mr Lechleiter. “That’s why we’re looking at treating people who have no symptoms, but have the plaque, to see whether we can delay the onset of the disease.”

It is the results from this trial — due next year — that will make or break solanezumab. But positive data this week from the extension of the previous trial would increase confidence of success. With Merck also making progress on a product, the chances of the first disease-modifying drug reaching market in the next few years seem to be rising.

Wall Street excitement

This has sparked a change of sentiment among investors. Shares in Eli Lilly are up 26 per cent since the start of the year in large part because of growing hope that its Alzheimer’s bet will pay off.

Nothing demonstrates Wall Street’s new enthusiasm for dementia research better than the initial public offering last month by a Bermuda-based company called Axovant Sciences on the New York Stock Exchange. Its sole asset is an experimental Alzheimer’s drug bought from GlaxoSmithKline last year for $5m after it failed in four clinical trials. Yet, Axovant says a close reading of the data suggests it still has a chance of success and on this basis it raised $315m and achieved a $2bn valuation in one of the biggest biotech IPOs on record.

Sceptics fear investors are getting carried away. Dr Karran points out that there has not been a big breakthrough of the kind that is currently causing excitement about the new class of cancer-busting immunotherapies. Instead, the new-found optimism stems largely from the reinforcement by Biogen and Eli Lilly of existing science. “It just means there’s less risk that the last 25 years have been wasted.”

Still, there are signs of broader momentum. As politicians wake up to the scale of dementia’s social and economic burden, more public funds and policy attention are being committed to the problem. There is still a relative lack of investment — the UK government and charities spend about eight times more on cancer research than dementia — but measures are being put in place to narrow the gap. David Cameron, UK prime minister, this year launched a $100m Dementia Discovery Fund backed by industry and government to support early-stage research.

Podcast

Alzheimer’s affects tens of millions of people around the world and the goal of an effective treatment has been so elusive that it is seen as a ‘black hole’ for drugs spending. But now Andrew Ward and David Crow find fresh hope of a breakthrough

Doug Brown, director of research at the Alzheimer’s Society, likens the growing scientific and political traction to past tipping points against other diseases. “This is what happened to cancer in the 1960s and HIV/Aids in the 1990s. Now it’s happening in dementia.”

Yet, the challenges remain immense. Only when drugs start completing successful trials and reaching market will the industry be sure it is on the right track. Even then, says Mr Clarke, at Eli Lilly’s Surrey laboratories the battle will be far from won.

“The first drugs are going to slow the trajectory and then we have to keep building on that towards a cure. The industry is going to be working on this for many years to come.”

Comments