Herzl, by Shlomo Avineri

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Herzl, by Shlomo Avineri, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, RRP£20, 288 pages

There is a passage in Theodor Herzl’s 1902 romance of a reborn Jewish commonwealth, Altneuland, in which he wheels on a Haifa Arab, Rashid Bey, who is asked whether “the older inhabitants of Palestine are not ruined by Jewish immigration?” The reply, painfully poignant now, testifies to the wishful thinking of the founders of Zionism. Bey and his family have not only stayed; they have prospered alongside the Jews, equal citizens in the New Society, as Herzl calls it.

As Shlomo Avineri observes in his fine new biography of the father of political Zionism, before writing this off as patronising colonialism, one ought to pause to ask what actually was so wrong about that vision of a shared Israel-Palestine grounded in social justice and mutual interest. What Herzl was against is made even clearer a little further on in the novella, when opposed ciphers for the Zionist vision contend for votes in an imagined agricultural settlement. The socialist argues that “we do not ask what race or religion a man belongs to. If he is a human being that is enough for us.” His opponent, a rabbi and erstwhile anti-Zionist, insists that the “Old-New Land” is exclusively for the Jews. In Herzl’s novel, the pluralist trounces the chauvinist. If only.

The wilful grandeur of Herzl’s political imagination has always provoked strong reactions. In his brief life (he died aged 44, in 1904) he was thought, not altogether without reason, to be a Viennese intellectual patrician, too remote from the misery of eastern European Yiddish-speaking Jews to understand either the relentlessness of their persecution or their ancient devotion to a specifically Palestinian homeland. In his final years, this changed dramatically and Herzl was worshipped in the towns and shtetls as a messiah. For those who regard Zionism as a historical mistake (or worse), Herzl embodies everything wrong with it: myopic about the indigenous Arab population; a naive suitor to any imperial government that might promote an autonomous Jewish state, as if Palestine was theirs to dispose of; someone so deracinated from Jewish tradition as to suppose a sovereign Jewish state could be plonked down in whatever part of the world might be made available: Argentina, Cyprus or Uganda.

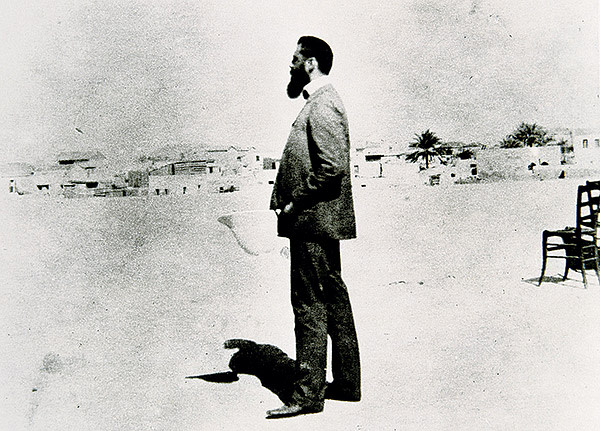

Some of this portrait is recognisable in historical reality; much of it is caricature. The great strength of Avineri’s immensely readable biography is to deliver Herzl in all his tortured complexity and – something not always given its due – the philosophical clarity of his diagnosis of what had befallen the Jews in the modern age and what might be done about their predicament. He had the beard of a poet but a brain for realpolitik. As one might expect from Avineri, who is first and foremost a powerful historian of political thought, this is the most chewily cogent account yet of Herzl the political thinker and doer. But the unhappily married husband, the wannabe novelist, the dutiful lawyer, the spiky journalist, and the impulsive dreamer who one day could imagine a mass conversion of the Jews before St Stephen’s Cathedral, the next a new Zion, also march briskly through his pages.

At the heart of the story is the failure, for the Jews, of the emancipation project of the European Enlightenment. Avineri recognises the paradox that it was precisely those who most seemed to personify its success – assimilated bourgeois professional Jews in cities such as Vienna – who understood with chilling clarity the brutal limits of their acceptance in the modern world. Herzl’s play The New Ghetto (1898) may not have been much cop as drama but it made the point that the Jews had exited from the segregation imposed on them by Christian prejudice only to discover they were still treated as aliens lodged parasitically in the cities of Europe. Everything they had been told would end their oppression and which they had ardently embraced – patriotism; immersion in the language and culture of their country; secular education; modern dress – had only made matters worse. Now, their indistinguishability was taken to be the subterfuge of masked domination.

In 1895, Karl Lueger was elected as mayor of Vienna on the strength of his populist anti-Semitism and Herzl, returned from reporting on the trial of Dreyfus in Paris, knew the game was up. In common with all recent studies, Avineri is a little too emphatic in insisting on the irrelevance of the Dreyfus case to Herzl’s Zionism. It may well be that during the proceedings he was indifferent to its victim, at first believing him probably guilty, but as the “affair” proper got going, he was anything but. Four years later, in 1899, he wrote that the grotesque miscarriage of justice had revoked the revolution’s promise of extending the Rights of Man to the Jews. It is true, though, that it was exposure to violent rhetoric of German writers such as Eugen Dühring, who called for the confiscation of Jewish property, which began the process of creative alarm that would end in the writing of The Jewish State (1896).

Herzl was not the first Zionist. Karl Marx’s co-editor and friend, the communist Moses Hess, despairing of ever being permitted true social solidarity with brother workers, argued in Rome and Jerusalem (1862) that it could only be achieved in a sovereign Jewish republic. Leo Pinsker, the Odessa doctor whom Herzl only belatedly discovered, responded to horrific pogroms by insisting that only when the Jews ended their homelessness, a condition that ensured they would always be treated as despised supplicants, would they finally be treated as fully human.

The Jewish State and the creation of a Zionist Congress in 1897 turned disparate local efforts into a template for national rebirth. Herzl had given the Jews a collective identity that was in contrast to a religious tradition that assumed God alone worked the controls of history. This was the precondition of being taken seriously by the powers of the world, even if only to further their imperial interests. These were seldom philo-Semitic. Faced with the masses of impoverished Jews, the ruling classes in Germany, Russia and Britain all thought it would be a fine idea to send them off into some remote and isolated Zion. Jews in El Arish, Argentina or Uganda would be altogether preferable to the smell of herring in Minsk or Whitechapel.

So they all gave Herzl the time of day. Not much, though. Avineri begins his book with the tragicomedy of Herzl, summoned to interviews with Wilhelm II, first in Constantinople and then in Palestine where he waited, top hat in hand, to ambush the Kaiser with polite importuning at the roadside. It was the growing sense of being cynically used, and the certainty that the Turks would never countenance any alienation of sovereignty in Palestine, that prompted Herzl to contemplate alternatives in Africa and South America as way stations to Zion. The recoil effect among Zionists, for whom the cause was meaningless unless rooted in the place where Jewish identity had been created, nearly broke the movement.

It is easy to list Herzl’s shortcomings. In his desperation to get Jews out of a world that was growing unmistakably more, not less, murderously hostile to them, he was over-optimistic about the mutualism of Arabs and Jews in Palestine, though he was prescient about the rise of Egyptian and Syrian nationalism and welcomed it. But neither he nor the Zionism he created was without genuine idealism. In the new city he wanted to build outside the walls of a restored Jerusalem, there was to be a Palace of Peace. Even now, that project deserves more than a hollow laugh.

Simon Schama is an FT contributing editor and author of ‘The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words 1000 BCE-1492’ (Bodley Head)

Comments