The conflict of interest in free news

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For a man running a small business, Michael Arrington has attracted a lot of attention in the past couple of weeks. By the time he agreed to leave AOL this week, he had stirred up a maelstrom across Silicon Valley and the digital media.

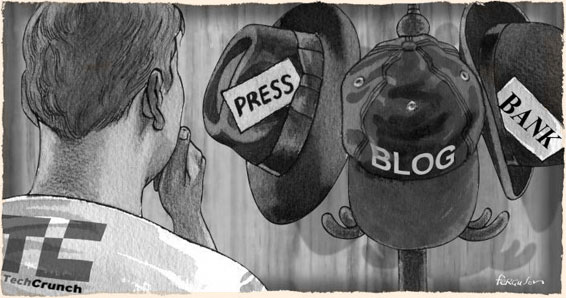

His move to use his technology news outfit TechCrunch to find investments for his new $20m venture capital fund became a conflict of interest minefield. Tim Armstrong, AOL’s chief executive, at first argued that TechCrunch was a “different property” with “different standards” from AOL’s other news outlets, led by The Huffington Post. He was rapidly forced to change his mind.

What did he expect from Mr Arrington, whose company AOL bought last year for $30m? “TechCrunch is a new kind of publication,” the latter wrote during a previous dispute in 2006. “[It] is all about insider information and conflicts of interest. No one should think TechCrunch is objective or conflict-free. We aren’t.”

More to the point, what did anyone expect in a world where what would once have been a subscription newsletter became a free blog that relied on low-yield advertising? If publishers cannot make money in legitimate ways, someone will invent a dubious way instead.

“Information wants to be free. Information also wants to be expensive. That tension will not go away,” wrote Stewart Brand, the technology entrepreneur, in 1985. Mr Arrington has proved it – especially the part about tension.

The news business is experiencing a similar evolution to investment banking after deregulation on Wall Street in 1975, and in the City of London in 1986. The abolition of fixed commissions led to a squeeze on investment research, for which institutions had paid, and a search for a new source of revenue.

Eventually, ignoring the conflicts of interest, investment banks came up with the idea of getting companies rather than investors to pay for the analysts by using the latter to market initial public offerings. That culminated in the IPO research scandal when the 1990s internet bubble burst.

That, in effect, is what Mr Arrington wanted to do. He lacked the subscription and high-yield print advertising that sustained publishers in the past. So he tried to “monetise” – the ugly term for making money from free content – his network by using it to draw venture capitalists to his CrunchFund.

The lure for them was that access to TechCrunch’s intelligence would allow them to spot the next Google or Facebook early on. Meanwhile, which aspiring technology start-up would not want to hand exclusive stories to TechCrunch to improve its chances of gaining favour from Mr Arrington and his fellow investors? It would be good for everyone.

Except, of course, that it was rife with conflicts of interest. Would news coverage be slanted to favour sites in which CrunchFund or Mr Arrington invested? Would venture capitalists feel forced to cough up in order to ensure that their own deals were covered on TechCrunch? Human nature and financial incentives being what they are, both were very likely.

Before being ejected under pressure from Arianna Huffington, now editor-in-chief at AOL, Mr Arrington loudly denied it. The old media types who griped about him had their own conflicts and were jealous of the new information paradigm that he had invented, he said. He could be both an investor and an impartial observer.

Mr Arrington has the “crazy man” defence on his side – that he is so excitable and grouchy that no one can rely upon his loyalty. He is constitutionally incapable of holding back from expressing his opinion in public, even if he holds an investment or sits on the board of a company he is damning.

He is also right that traditional news outlets have their own conflicts – even if they formally separate their commercial and editorial operations, reporters face the temptation to trade favourable coverage for inside access. But individual misbehaviour is one thing; a fully-fledged business model is another.

His argument is essentially the same as that of Goldman Sachs and other Wall Street banks: “Yes, we have enormous conflicts of interest but being on different sides of deals gives us privileged information flow that benefits our clients. And you can trust us to manage the conflicts, since we are decent people.”

We all know where this led – both to the IPO scandal, in which analysts’ coverage was slanted to gain business from issuers, and to the 2008 crisis. Goldman later settled on charges of securities fraud, admitting that it did not fully disclose conflicting interests in its Abacus mortgage deal.

The truth is that, no matter how loudly people protest that they have safeguards in place and will not abuse their power, conflicts of interest lead to abuses as surely as rivers flow to the sea. Even if they are disclosed in disclaimers, as banks now do with investment research, bad things will happen.

There are other ways to subsidise or profit from digital news that do not cause such conflicts. One is by linking news to data – the method chosen by Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg. Another trick is to sell a rapidly-growing but marginally profitable site to a big company at an inflated price, as did both Mr Arrington and Ms Huffington.

But if readers are not asked to pay and advertisers will not pay enough, that leaves a gap that must be filled somehow. Mr Arrington was forced to leave TechCrunch because his way of making money from news and information became too embarrassing for AOL. Others will face the same temptation.

Comments