Nick Waplington remembers Alexander McQueen

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In all the myths that have grown up and paeans that have been sung since the suicide of the designer Lee Alexander McQueen in February 2010 – tales of the creative genius too sensitive for this world, foul-mouthed visionary and East End boy who reached the most gilded salons of the Avenue Montaigne – there has been one glaring omission: the extent to which McQueen was conscious of his own actions, and crafted his own legacy. It has always seemed a disservice to his memory to eschew the truths about his canny management of both his business and his image, in favour of the more dramatic, but not necessarily more valuable, stories of his excess and extreme aesthetic. This was, after all, the first Young British Designer to combine commerce and creativity from the beginning in the form of corporate sponsorship, as well as ownership. And that’s a major achievement.

Since McQueen’s death, there has been no shortage of books on his life and work. The past year alone has seen the publication of at least four, including the unquestionably beautiful coffee-table tomes Alexander McQueen: Evolution and Love Looks Not With the Eyes. All followed the success of the 2011 Metropolitan Museum publication that accompanied the record-breaking retrospective Savage Beauty, and all focused largely on McQueen’s shows and sensibility.

Yet none of these books really goes beyond the accepted vision. Even Love Looks Not With the Eyes, a chronicle by photographer Anne Deniau of 13 years spent following McQueen, is more hagiography than revelatory. Which is why the latest contribution to the McQueen canon, Nick Waplington’s Alexander McQueen: Working Process, is such a surprise. It draws the curtain back on McQueen’s cultivation of his own enfant-terrible image to expose the strategic mind that coexisted with the outsize imagination.

Perhaps most significantly, the final edit of more than 120 photographs, which document the production of the 2009 autumn/winter collection Horn of Plenty, was actually made by the designer. Unlike every other book out today, Working Process is a portrait of McQueen as McQueen, at the end of his life, saw himself.

“He was always very concerned about his legacy,” says Waplington, a British photographer better known for studies of the environment and of communities that range from Israeli settlers to a Nottingham housing estate. “He wanted to give reality to who he was. There are a lot of myths, and a lot of them are of his own making, and this was about trying to put some facts down.”

Or, as the journalist Susannah Frankel, one of McQueen’s closest collaborators, writes in the introductory essay: “This project offers unprecedented insight into the mind of a notoriously private and at times wilfully impenetrable man. McQueen allowed only very few people into his workplace and even then behind-the-scenes access to preparations for the show was, to all intents and purposes, barred.”

Waplington was on the fringes of McQueen’s East End social circle in the 1990s, a friend of the stylist Katy England, who later became McQueen’s creative director. Then in 2008 McQueen contacted him and “asked me to document his working process”. It was the designer’s 15th anniversary show and he had decided to explore the idea of recycling through the prism of his own work, taking inspiration, materials, references and even models from his past seasons and reinventing them for the present day.

…

Waplington, who was living in Israel at the time and documenting the settlers on the West Bank, asked if they could postpone the project for a few years until he was back in the UK, but McQueen was adamant about the timing, and that this show be the subject. “He was very insistent,” says Waplington. “Of course, after the fact, I have wondered if there was more to it than just the anniversary … I can’t say it hasn’t crossed my mind. But at the time, I was mostly surprised and honoured that he wanted me.”

Indeed, though Waplington had shot the fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi for an advertising campaign while working with Richard Avedon in the 1990s, he had never had such a commission before. Even so, he was McQueen’s first (and only) choice for the project. As to why, Waplington can only guess. “He wanted something mucky and messy, which is what I do.”

There were no restrictions placed on his work, aside from the insistence by the Gucci Group, which bought a majority stake in McQueen’s fashion house in 2000, that Waplington not photograph “anyone smoking inside the London studio”. (Apparently the local council had its own rules about smoking in the McQueen building.) Given that the only smoker was McQueen himself, though, Waplington decided to do it anyway. “What can they do now, sue him?” he asks. Besides, he adds, “I was there to take pictures of the situation” – whatever that situation happened to be.

…

He spent six months following McQueen from London to Paris, from conception to catwalk to post-catwalk, and shot thousands of photographs: McQueen at rest, in frenetic action, reading Tourism and Sex – an analysis of sex tourism by Stephen Clift and Simon Cook – pinning, laughing, working with long-time colleagues such as Sarah Burton (who took over as creative director after McQueen’s death) and hairdresser Guido Palau, shirts untucked, shoes off; if not warts, then certainly wilfulness and all.

“When he was being nice, he was fantastic, but there were times he was in one of his famous ‘moods’ – though then he generally didn’t turn up,” Waplington says. “His schedule was pretty erratic. Sometimes, when I had flown in from Israel, I could get a little agitated about him not being there. But really, he was king of his castle. What he did was up to him.”

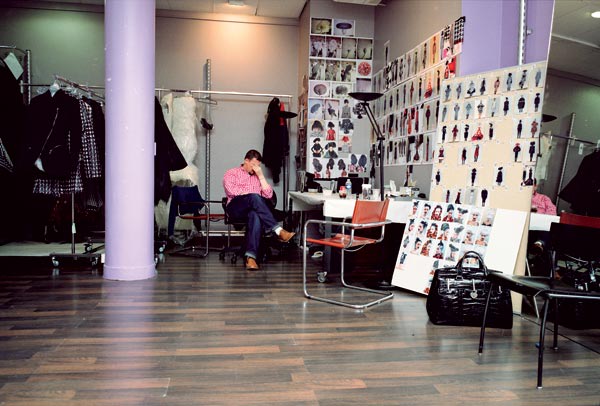

What struck Waplington most was the rhythm of McQueen’s creation. “It was almost Jackson Pollock-style. He would be sitting, smoking, in a chair, and then suddenly jump up and start draping cloth or pinning. It was very fast, and I felt it was very important to capture and contrast both moments.

“I tried to get him to go through the contact sheets with me afterwards,” Waplington continues, “but he kept getting distracted by how he looked” – McQueen famously lost a lot of weight after becoming part of Tom Ford’s Gucci Group – “so, in the end, I made 600 working prints and let him edit from there.”

The choices sometimes surprised him; in particular a still life of McQueen’s desk featuring chocolate bars and an Indian takeaway, and another picture of him “making very camp movements with his arms”. At one point, McQueen also tried to edit out his long-time collaborator, the milliner Philip Treacy. “I think he was miffed because Philip and I were friends who’d been at college together, but I said you can’t edit him out completely, he’s too important, and the pictures eventually reappeared.” There are 10 pictures of Treacy working with McQueen on the extraordinary hats that appeared in the show, from lampshade-like creations to what look like giant balls of yarn and vacuum-cleaner coils.

In addition, Waplington says, he was taken aback by “how nervous” McQueen was when Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of US Vogue, arrived to preview the collection – and the fact that he chose to include a photograph of her visit in the book, preceded by one of him with his head in his hands. Together with the desk shot and the gesturing, these are the pictures that show both his humanity and fallibility, traits that in the world of designer-as-celebrity are rarely seen.

…

Indeed, the messiness of reality, and the way beauty can be created from chaos (also a theme of the collection) was emphasised by McQueen and Waplington’s joint decision to punctuate the book with photographs of piles of rubbish, littered landscapes and recycling plants to provide a dimension beyond the making of a collection itself; to emphasise the making of an idea.

“At a certain point, myth merges with reality, and what you are left with is history, and this is that point,” says Waplington. As a result, it’s not a coffee-table book: “It’s a historical record.”

The initial print run is 20,000 copies – compared with the average of 3,000 with which Waplington’s books generally begin. Part of that is undoubtedly because of the success of the Met show, and the apparent appetite for McQueen imagery. But part of it may also be because the publishing world understands, as the designer himself did, that sometimes the truth of what happens behind the catwalk is as valuable as what happens in front.

——————————————-

Vanessa Friedman is the FT’s fashion editor.

“Alexander McQueen: Working Process: Photographs by Nick Waplington” (£40) is published by Damiani on September 1.

To comment on this article, please email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments