Behold the Bolshoi

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It is a great company – the largest ballet ensemble in the world, vastly admired, emblematic of its nation and, indeed, of that emblematic art, Russian ballet, housed in a no less emblematic theatre.

At the end of this month the company returns to London where, in 1956, it made its astounding debut in the west, and political ice started to melt in western admiration for Russian artistry, the intensity of feeling seen in Russian dancing and generated in us by that dancing. That the Bolshoi Ballet is no stranger now but, rather, a greatly loved guest, is owed to the half-century in which Victor and Lilian Hochhauser have brought the company, and many other Russian dancers, musicians and orchestras, to Britain. (Think of Richter, Rostropovich, Oistrakh and the Kirov/Mariinsky ballet. The political and social effects and influences of what the Hochhausers have done to bring such understanding to the political scene are in calculable.)

But consider also, as we must, the Bolshoi Ballet riven with discord, which brought an acid attack on its current director, Sergei Filin, a near-blinded figure still undergoing treatment in a German hospital. Three people – Bolshoi company dancer Pavel Dmitrichenko and two men who were allegedly hired by him to attack Filin – are now detained. Dmitrichenko’s motives are still unclear, although professional disappointment and company rivalries seem to be leading candidates.

One should not, long experience tells me, be surprised that such tensions should exist in a ballet troupe, in Russia or elsewhere, albeit the means employed to punish supposed rejection of an artist seem more vile than any disappointment about a career can ever justify.

The previous director, Gennady Yanin, also suffered an attack that was deviously hateful, by means of the internet – photos or videos of sexual indiscretions sent out to the world, and to his family – but avoided the frightful physicality of the Filin attack with acid. The extreme malevolence of this latter action argues something more actively evil. It also presupposes a wholly irrational idea of how the artistic policies of a national ballet troupe might be altered. Or punished.

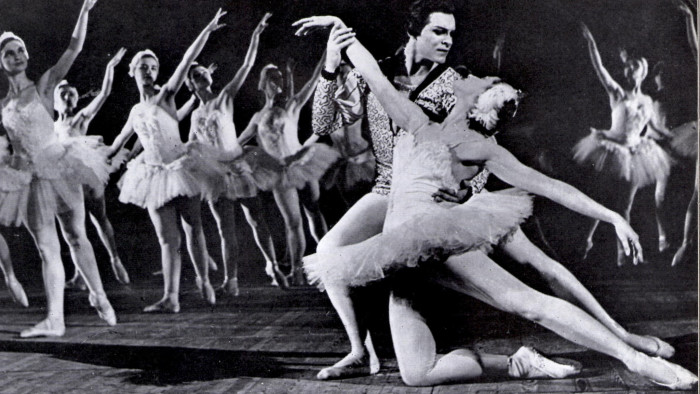

We do not know the extent, or even the nature, of the causes. But dancers’ careers are short and the enclosed world of a great ensemble, with an ethic that insists on extreme physical attainment, can breed a sense of injustice, of favouritism, and wholly unbalanced responses. Thirty years ago I talked to Yuri Grigorovich, who had been director of the Bolshoi Ballet for three decades as well as being its chief choreographer – such works as Spartacus (1968), Ivan the Terrible (1975) and The Golden Age (1982) were massive declarations about his massive ensemble – and I asked him about the nature of the company and how he remained its master.

“Two hundred dancers – two hundred temperaments!” was his answer, and implicit was the sense that his long experience, his choreographic spectaculars that engaged enormous company efforts, and an innate force of personality, were necessary to control the troupe. There was opposition to his rule, with such great names as Maya Plisetskaya and Vladimir Vasiliev voicing discontent. But the larger part of the troupe supported him. I asked a ballerina about a forthcoming company meeting in which discontents were to be aired: “Oh, I am one of Yuri Nikolayevich’s soldiers,” was the answer.

The lamentable events of the Filin scandal – reported worldwide with too much lurid opinion and merry rumour as decoration – are part of the problems that have affected the ballet troupe since the collapse of the Soviet system. Emerging into the post-Soviet years, the Bolshoi Ballet lost the discipline of Grigorovich’s regime, and was then to find itself exiled from its own theatre. Like the society that supported it, the building was no longer secure. Dangerously weak as a structure, the Bolshoi Theatre needed seven years of rebuilding, prodigious expenditure and prodigious respect for its past identity, which have brought a superb renewal.

It is Anatoly Iksanov, as general director of the theatre, who has seen the theatre and its ensembles through the tribulations and disruptions of the rebuilding. The Moscow troupe’s grandeur, the implications of its size as ensemble and emblem of Russian art, we accept and marvel at. The renewal of the theatre came not without big delays and eye-popping costs but brought no less eye-popping splendours in rebuilding and redecoration to provide opera and ballet with a setting that combines every modern advantage with a devotion to an identity earned during 200 years of musical and choreographic history.

Set against this, though, have been the uncertainties of finding an artistic policy. Since Grigorovich departed in 1995, there has been a succession of directors of the ballet: Vladimir Vasiliev, Alexei Fadeyechev, Boris Akimov and, from 2004 to 2009, Alexei Ratmansky, who set about reviving the repertory with a sequence of skilled renewals of former Bolshoi stagings. Ratmansky was succeeded by Yuri Burlaka, then by the pilloried Gennady Yanin, and now by Sergei Filin.

I incline to a belief that the post-Grigorovich years are part of an inevitable historical process. The worst blow was that Ratmansky, an undeniably gifted choreographer, opted to move to the west. Not the least of his gifts was a vision of how to deal with Soviet-era creativity by renewing and reshaping the old dram-ballets of the Stalin years and effectively linking past and present. The Bolshoi needs another Ratmansky – or another Grigorovich – who will nurture a creativity as vivid and of its time as Spartacus, which spoke of Soviet ideals, or The Bright Stream, which was Ratmansky’s own felicitous look at Russia’s and the Bolshoi’s own history. Meantime, the other central fact of the troupe – its grandeur of style and massive integrity in performance – is still life-enhancing, still marvellous, still truly Russian.

——————————————-

The Bolshoi Ballet will perform at the Royal Opera House from July 29 to August 17; www.roh.org.uk

Comments