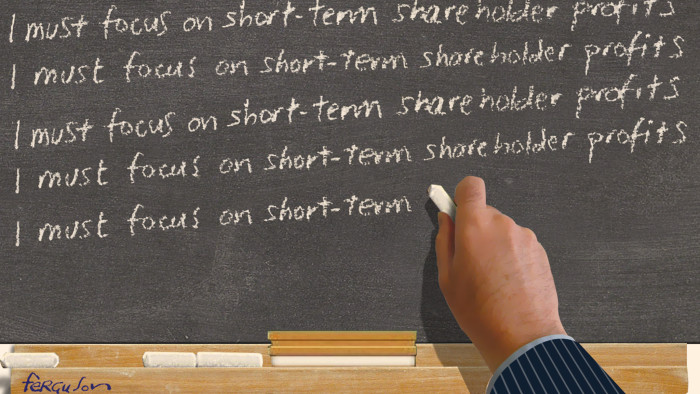

MBA teaching urged to move away from focus on shareholder primacy model

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

While there is growing consensus that focusing on short-term shareholder value is not only bad for society but also leads to poor business results, much MBA teaching remains shaped by the shareholder primacy model. Yet for reasons ranging from the tenure system to institutional inertia, moving away from this model will be tough.

Academics and others are becoming increasingly vocal about how deeply entrenched the idea of shareholder primacy is in management education.

“The prevailing view in business schools has been that a primary function of corporations is to further the interests of their shareholders,” says Colin Mayer, professor of management studies at Oxford’s Saïd Business School and the author of Firm Commitment.

Craig Smith, professor of ethics and social responsibility at Insead, agrees. “Students come in with a more rounded view of what managers are supposed to do but when they go out, they think it’s all about maximising shareholder value,” he says.

The persistence of this idea in MBA teaching comes as some companies – from Nestlé and Unilever to Costco, PepsiCo and Starbucks – are developing strategies that focus less on short-term share value and embrace long-term environmental sustainability and inclusive business models.

Mixed messages in the classroom

Surveys, studies and papers point to the fact that shareholder primacy remains the organising principle behind the MBA in many business schools and continues to dominates management education culture.

“It’s almost as if the world knows something business schools don’t,” says Thomas Donaldson, professor of legal studies and business ethics at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton school. “They’re holed up in a fort surrounded by people who see it differently – but they get to stand in front of the class with the chalk.”

The dominance of shareholder primacy in business schools is a relatively recent phenomenon. For most of the 20th century, schools emphasised the theory of managerialism, says Lynn Stout, a Cornell Law School professor and author of The Shareholder Value Myth.

“This treated company executives as stewards entrusted with running organisations that had economic and social purposes in the interests of a wide range of beneficiaries,” she says.

So what changed? Influential opinions have played a role, including Milton Friedman’s 1970 New York Times article The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.

Most agree that a turning point was the 1976 paper co-authored by Michael Jensen and William Meckling, Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership.

Among the most frequently cited economics papers of the past three decades, it argued that the problem in companies was that executives were serving their own interests rather than those of owners, or shareholders. Proponents of this “agency theory” argued for incentives for managers to increase the value of the company.

At business schools, changes in the make-up of the teaching faculty and academic priorities reinforced interest in the theory. In the late 1990s, schools responded to the stock market boom by hiring more finance professors and – under fire for relying on the knowledge of practitioners – sought more empirical rigour in course content.

This gave the neat simplicity of the shareholder primacy model enormous appeal. “If we can skip discussions of corporate purpose by stipulating that corporations exist to create shareholder value, it makes it easier to get down to the more technical details of how we get there,” says Gerald Davis, a management professor at University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

Business students: MBA students from business schools around the globe blog their experiences

It has also given the model staying power in the MBA. “A generation later, the reason it has so much currency is because it’s simple, elegant and easy to measure,” says Judith Samuelson, director of the Aspen Institute’s Business and Society Programme. “But simple and measurable doesn’t mean it’s correct.”

Yet while an increasing number of business school deans, academics and others agree on the need to shift the focus from shareholder primacy, the path to a new model of MBA teaching is strewn with obstacles.

Time pressures and resistance to change are tough to overcome. “The forces of institutional inertia are enormous,” says Prof Stout. “No professor wants to be told they need to completely rework their course material.”

The tenure system creates another obstacle, since tenured teaching faculty face little pressure to change course materials or teaching methods. “And scholars who come on later and are being judged by their elders need to stay inside the paradigm to be tenured,” says Ms Samuelson.

Shareholder primacy also seems at odds with sustainability courses, which emphasise long-term strategies and the consideration of a range of stakeholders, from customers to communities, in business decisions.

Yet despite their popularity with students, schools have often struggled to integrate these topics into core courses. Many sustainability courses remain in electives, or as what Prof Donaldson calls “satellites …circling around the real planet”.

Some argue that if capital markets accurately reflect future cash flows, sustainability could be compatible with shareholder primacy. “If CSR [corporate social responsibility] and sustainability really do pay off, then there should be no conflict,” says Prof Davis.

However, this requires emphasising long-term rather than short-term shareholder value. “If one can demonstrate that companies that emphasise long-term shareholder performance overtake other corporations,” says Prof Mayer, “that becomes persuasive evidence for rethinking the model.”

Of course, in providing this evidence, academics have much work ahead. Companies are still grappling with putting hard numbers on the financial returns of long-term environmental investments or of including local communities in their business strategies.

But as seen with the introduction of courses on sustainability, a powerful force for a shift in the teaching of corporate purpose in the MBA, may come from the students themselves. Prof Mayer certainly thinks so. “If anything,” he says, “the drive for this change is most likely to come from the student body that’s increasingly questioning the standard view.”

Comments