Will the Dubai Film Festival ever rival Cannes?

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Dubai has transformed shopping and globe-trotting in the 21st century. Not content with dragging tourism and consumerism into the future by the scruffs of their designer necks, the Emirates’ show city is now moving in on high or medium-stature culture.

Cinema is its proudest achievement sector so far. If the Dubai International Film Festival (Diff) has its way – the 10th annual event ended last Sunday – the magic carpet of the moving image is floating towards it from Cannes, Venice, Sundance and Co. Diff has designs on their supremacy.

As a Dubai virgin – never exposed to the city before, but invited to serve on one of the seven festival juries – I was ready prey for the sense-boggling opulence of Arab hospitality.

The festival does nothing by halves or even by conventional wholes. Cannes and Venice may be satisfied with two big parties apiece, to open and close their events. The Dubai parties go on every night, after every red-carpet gala.

To be a top film festival, however, you must have the best films, not just the best parties. Cannes, for the moment, can breathe easy. My own jury’s viewings consisted of a programme of 10 “AsiaAfrica” films, of which five were modest and two worse. The best more skilfully parlayed indigenous issues or preoccupations into world-appeal cinema. Singapore’s Ilo Ilo (Best Film winner), Iran’s Fish and Cat and India’s The Lunchbox are all ready for the world art house: an astringently touching family drama, a tour de force puzzle picture about time and memory, and a clever, surprise-springing love story.

Mohamed Khan’s Factory Girl from Egypt and Laila Marrakchi’s Rock the Casbah from Morocco, woman-oriented stories and one woman-directed, both fall into the “woman’s picture” trap. Love versus labour struggles; a mother re-bonding with daughters at the funeral of a patriarch (flashback-played by a slyly ageless Omar Sharif). The movies suggest, perhaps intentionally but not very robustly, the vitiated lives left to sensitive women by men who pull society’s strings and shape its dramas.

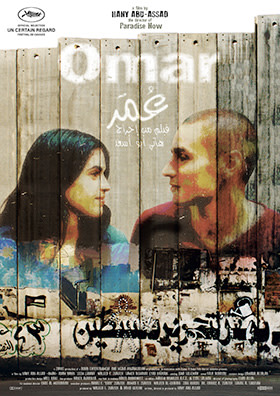

Beyond that section, I saw four new Arab films. Only Hany Abu-Assad’s Omar, the opening night feature from the director of the widely praised Paradise Now (2005), was of international stature. And even this well-acted, strongly scripted Palestinian terrorist drama had already won a prize at Cannes. The gongs gained here – Best Arab Feature and Best Arab Director – seemed a tardy hurrah.

It wasn’t always easy to find a way through the complex programming of films. To compete as a festival, Dubai should also learn how to make participants feel oriented, not just orientalised. The Arabian Nights ambience is terrific. But guests kept getting lost. Couldn’t we have a working map of the souks, canals and labyrinthine festival headquarters and theatre?

Partly the disorientation was subtler and deeper. The “Cultural Breakfast” laid on by the Diff proved to be not the brochure’s mosque and museum tour plus light repast but an argumentative seminar, with some side eats, hosted by a white-robed teacher/preacher determined to assault western prejudices. At one point he robed a girl in our party – a jeans-wearing Saudi – in the traditional black dress plus scarf and veil to illustrate his argument that these raiments are not only practical for women but preferred by them. Black is a comfortable colour even in heat (he said). Veils keep out sandstorms. And a woman would of course be permitted to wear a different colour if she wanted, he answered when, speaking up for my group, I ventured the word “patriarchy”.

Even so, it becomes impossible to dislike Dubai. The modern city stands there stupendous, a work of human will wrought to a pitch of miracle. A megalopolis that stops the breath was created by promotion, investment and entrepreneurial panache; by calls to plutocracy, worldwide, as shrill yet hypnotic as the calls to prayer that punctuate the Dubai day.

The film festival itself, though generous and glittering, needs to do three things to rival Cannes and its peers. When its selectors trawl for movies it must throw the sprats, tiddlers and under-achievers back in the Gulf. It must streamline programming so there are fewer sections, not this year’s hydra-headed seven, each with its own jury and cultural jurisdiction.

Third and chiefly, the show’s the thing. I loved the parties. (Who couldn’t?) But are we here for culture or consumption? A bad film doesn’t improve the appetite for the champagne and dancing girls. Nor do the ghastly 15 minutes of sponsor adverts before each gala film.

Those who deride Dubai will say: “Well, of course. You’re being softened up for your consumer duties. Culture first, then out with the credit cards. Viewing wears down the viewer’s resistance. It’s ‘Drop till you shop.’ ”

Part of me wants to believe, though, that the organisers do want to organise a good festival. They want to blow the fresh air of film and film-making through the stale cloisters of, let’s say it again, patriarchy. Isn’t it heartening, this year, that 40 per cent of the Arab films shown were made by women?

Consumerism too may have its place. Is it quite the enemy of culture that we’re taught to believe? In a festival-organised gift room one object of art or craft, or both, caught my eye instantly. It was by Dubai-based Briton Yasemin Richie. Her speciality is to take a famous film and compress its scene-by-scene dominant colours into a CinemaScope-shaped sheaf of rainbow tones, a prismatic block of different sequenced hues: a movie as objet d’art. (I chose the green-and-black-dominated The Matrix.) A Richie work is also obliquely and suggestively “about” culture as consumerism.

International culture is a tariff-free traffic of art and ideas. We critics and jurors feel liberatingly “duty-freed” – or duty-transcending – when the films we see are packaged with parties, symposia, trips and enriching glimpses of an eastern wonderland. As in the Richie works (which she names “Storylines”), so at Diff. Our cinema experience is magicked into a different, though never wholly unfaithful, narrative. Leaving Dubai the festivalgoer is not quite sure – in the best sense – whether he is taking with him the movies he saw, the marvels he experienced, or a “storyline” in which these memories mix with and enrich each other.

Comments