How Nelson Mandela’s example offers style lessons for a new year

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Almost a month after the death of Nelson Mandela, every talking head has weighed in with their own memoir or eulogy so what is there to add? Fair question.

Let me simply say that this is a new year’s column – a look forward, not a look back – and it is about a lesson I think worth taking from Mandela and applying in 2014, a lesson not included in the many “Lessons from Mandela” written in recent weeks. Most of these were concerned with choosing reconciliation over revolution, while this is to do with clothes. It may seem like a frivolous topic where someone such as Mandela is concerned, except he clearly took clothes – and their power – seriously, and perhaps we should, too.

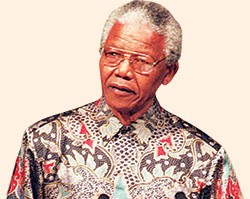

In a world where leaders rarely stray from an accepted uniform, no matter where they live – dark suit, white or blue shirt, red or blue tie – Mandela stood out in his colourful batik shirts. They not only made him visible wherever he went but served a variety of more covert purposes: advertising his independence from what went before, underscoring his allegiance with the traditions of his country and providing a form of outreach to minority groups that each interpreted in their own way.

More than any leader I can think of, Mandela demonstrated how clothes can be a strategic expression of individuality, even for a politician. And he did it without adopting another widely used uniform, the military jacket – the general default option ever since Napoleon.

Picture any G8 or even G20 meeting and, women aside, there is a startling homogeneity to the dress, the theory being that those who dress alike, negotiate alike. As the former Indonesian vice-president Jusuf Kalla was quoted as saying: “Nelson Mandela dared to wear batik in the UN General Assembly. If it was me, then I might still hesitate to wear batik and speak in the UN General Assembly, but he did not.”

Consider the fact, however, that, when he was elected, Mandela wore a suit and tie just like every other man in his position. It was only after a few months that he began to wear batik – and wear it, and wear it, to the extent that it became so synonymous with his image that it took his name (the “Madiba” shirt), and when Giorgio Armani offered to dress him, he respectfully declined.

Mandela had found his signature. It meant: (a) anyone else who wore batik automatically became associated with him; and (b) when he chose to change from it, it was an act loaded with meaning. See, for example, when he wore a Springbok jersey in the 1995 Rugby World Cup, and the following year when he wore a “Bafana Bafana” football shirt for the African Cup of Nations. Not to mention his willingness to bend his own rules when necessary. According to the designer Oscar de la Renta, Mandela was once invited for dinner at the home of Harry Oppenheimer, then-chairman of De Beers – “as long as he wore a tie”. He wore the tie.

…

Like most symbols, the Madiba shirt became the subject of several origination myths. On the Judaism website chabad.org, a writer called Avraham Berkowitz recalls a conversation with Mandela about a visit to a Jewish synagogue in Cape Town in 1994 when a woman in the congregation gave him a black-and-gold fish-print shirt. According to Berkowitz, Mandela said: “After I’d worn that shirt, this same woman [white South African designer Desré Buirski] would continue to send me shirts. We become good friends, and she designed hundreds of shirts for me. These shirts help me carry my message all over the world.”

South African GQ, however, also attributes the shirts to fashion designer Sonwabile Ndamase, and points out that “by wearing fabrics rooted in southeast Asian cultures, Mandela reached out to the Cape Malay community of South Africans”. Burkina Faso-born tailor Pathé Ouédraogo is another reported provider of Mandela’s shirts.

Meanwhile, Indonesia has hailed Mandela for helping to make its batik globally known. It is said that President Suharto gave him his first batik shirt when Mandela visited the country shortly after his release from prison, and he also went on to wear many shirts by Indonesian designer Iwan Tirta. Mandela’s batik shirts were seen in Indonesia as a symbol of the parallels between South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement and its own anti-colonial movement.

Whatever the reality (and Mandela probably wore shirts by all of the above during his long batik-wearing career), it is clear this garment was not a bad communication tool. With clothing, as with politics, Mandela made different individuals feel connected to his cause and used his clothing to further his politics.

It is a model that other politicians might do well to consider. Suits are, no question, the safe option. Perhaps it’s time to think more broadly, not just about constituencies but about what constitutes imagineering. That is a resolution worth making in 2014.

——————————————-

vanessa.friedman@ft.com, @VVFriedman

More columns at ft.com/friedman

Comments