What will Brexit do to the FTSE, UK property and the pound?

The markets have had several days to digest David Cameron’s February 20 announcement that the UK will go to the polls in June for a historic vote on whether to leave the European Union. So how are they reacting to the prime minister’s move, and what should private investors expect to happen next?

The pound

Sterling has been hit by the prospect of a UK Brexit. Last week it plumbed a seven-year low against the dollar. It has fallen around 3.5 per cent against the dollar since February 19, which is a relatively large move over two weeks.

This is clearly great for tourists coming to the UK and British exporters but it also means that currency traders have a negative view of Britain’s future. Their downbeat mood comes amid predictions that Britain’s economic growth would falter as a result of severing political and trade ties with Europe.

Stephanie Flanders, chief market strategist for Europe, JPMorgan Asset Management, writes: “A negative result could take around 1 percentage point from the growth rate in the 12 months after the vote — a significant hit, given the baseline growth forecast of around 2 per cent in 2016.”

On the first trading day after Mr Cameron set the date for the Brexit vote, sterling dropped 1.3 per cent against the dollar, which was its largest fall since last May.

Ms Flanders calculates that the currency is 6.4 per cent lower against a group of currencies of the UK’s trading partners since the turn of the year.

One pound now buys around $1.39, down from almost $1.60 last June, although the fall since then must also be viewed in the context of a stronger dollar, after the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates last December for the first time in seven years.

The sterling swoon can also be explained by forecasts that, if UK GDP falters after a Brexit, the Bank of England will resume its asset buying quantitative easing programme, which would increase the supply of money in an attempt to ease economic woes, but also weaken the currency.

The EU referendum has cast a spotlight on weaknesses in the UK economy, such as the nation’s current account deficit, which is the shortfall between how much Britain spends overseas and how much other countries invest. Another reason for sterling’s weakness is that it is easy to trade.

A team of strategists at asset manager BlackRock write in a research note: “Sterling is most vulnerable to Brexit fears as it is the most liquid UK financial asset. A Brexit could pressure the UK’s budget and current account deficits, hurting the currency and potentially triggering credit downgrades. Conversely, we see depressed sterling bouncing back if the UK votes to stay.”

UK government debt

The government’s cost of borrowing, as expressed by the interest yields on the ten-year bonds the state sells to investors to fund its spending, has also risen on Brexit fears.

This “yield” on bonds as they trade in securities markets — which is really an implied cost of what the UK will pay to borrow the next time it sells its bonds at auction — is expressed as the coupon the bond pays to investors as a percentage of the price of the bond.

It has ticked up slightly from where it stood immediately before Mr Cameron’s Brexit vote announcement. It stands currently at 1.447 per cent, compared to 1.414 per cent on February 19.

This is not a big rise, but given that UK interest rates are set to stay low and economists are even predicting another round of quantitative easing by the Bank of England, were it not for Brexit, one could have expected the yield on these bonds, also known as “gilts”, to have fallen.

The BlackRock team forecast the government’s borrowing costs may rise further in the event of a Brexit, as foreign investors become less willing to extend credit to the UK.

“A leave vote would likely increase gilt yields,” they write. “[Investment] portfolio inflows could falter, pressuring domestic sources of funding for the budget deficit. We could see bank funding costs rise and credit spreads widen.”

Property

Some signs of Brexit fear may be showing in the market for ultra-expensive London properties - those worth £10m or more - where slight price falls have been recorded in the last six months. Prime London homes are affected by a range of geopolitical factors, however, and it is arguable that a slump in oil prices and economic slowdowns in emerging markets are putting off buyers from Russia, China and the Middle East.

Business investment

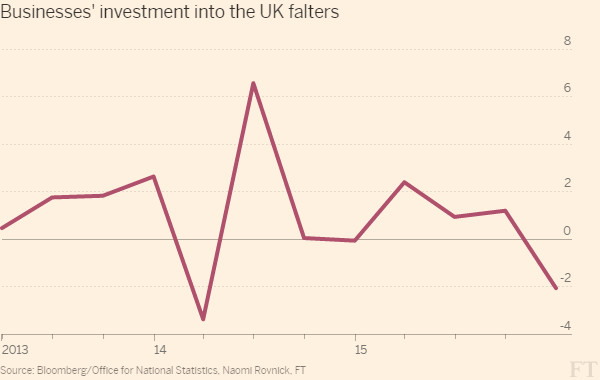

Businesses are also investing less in the UK, as they wait for the outcome of the vote. Recent official figures show that UK investment declined by 2.1 per cent in the final three months of 2015, after growing by an average of 1.4 per cent in the preceding nine months.

JPMorgan’s Ms Flanders writes: “We cannot know how much of this slowdown was due to referendum fears, but it underscores that this is an unfortunate time to be giving businesses something else to worry about.

“A 25 per cent reduction in the volume of investment due to the referendum could theoretically knock 0.25 percentage points off the annualised rate of growth in the economy in the second quarter.”

But British stocks, in other words the FTSE 100 and the FTSE 250, have both risen since Mr Cameron set the day for the Brexit vote.

The FTSE 100 is comprised of many businesses who make their money outside Britain, such as Anglo-Australian miners Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton, whose fortunes are more linked to Chinese growth and commodities demand than to UK politics.

And while the UK government is warning that Brexit would be bad for British exporters, the fall in sterling inspired by the referendum has boosted their shares, in the short term at least. Shares in Rolls-Royce and BAE Systems, for example, have had a very good few weeks as sterling weakened.

Analysts at consultancy Capital Economics point out that the FTSE surged 20 per cent in 1992, the year the UK left the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

Investors should not expect such outperformance in the FTSE 100 this time around. That is because sterling is unlikely to fall as sharply as it did upon Britain’s departure from the ERM.

John Higgins of Capital Economics says: “The decline in sterling [in 1992] was more sudden than the one that we foresee in the event of the UK electorate voting to stay out of the EU. Accordingly, there was more scope [then] for it to provide an immediate boost to equity prices [than there is now].

“Within the ERM, currency fluctuations were only allowed within tight bands around pre-agreed central rates against the ECU [the precursor to the euro]. In the case of sterling, this band was [plus or minus] 6 per cent. It was therefore only after the UK abandoned the ERM on “Black Wednesday” (September 16), that sterling plummeted.”

So private investors should not worry too much about the FTSE 100 in the short term. But they should keep an eye on any of their holdings that are sensitive to the performance of sterling, such as exporters, and to interest rates, including shares in banks and housebuilders, as well as physical property.

Brexit, of course, is by no means certain, and the world’s top economists are deeply divided in their forecasts. Justin Knight, a strategist at investment bank UBS, believes the UK will vote to remain. In that case, if the economy remains relatively strong, he sees the pound strengthening and interest rates rising.

“The relative strong dynamics in the UK economy — including those of confidence measures — have held up during the past few months and are likely to persist at least until the referendum takes place,” he writes.

“If the people of the United Kingdom vote to remain in the EU then it seems likely that the market would start to anticipate Bank of England rate rises once more and that sterling would strengthen to prior levels.”

Comments