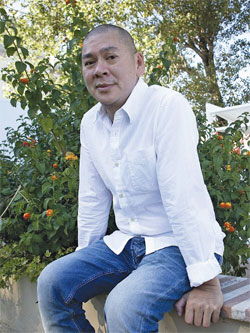

Tsai Ming-liang talks about ‘Stray Dogs’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

There are all sorts of silences in cinema. Some silences, holding in thrall both movie and audience, can be like a meeting of raptures, transporting characters and spectators alike to another, higher dimension.

At the Venice Film Festival, near the end of Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, there was an unbelievably long, static, silent shot: one that concentrated all the film’s tensions, unspoken yearnings and poetic powers. Two main characters stand close together, staring off into space, darkness or the unseen for what seems like a full 10 minutes.

“It’s actually 14,” Tsai says on a Venice hotel terrace. “The scene was longer when we filmed it but I decided to cut when the two characters first start to hug each other.”

Stray Dogs, Tsai’s 11th film and his best in years, won 2013’s runner-up Grand Jury Prize. It was pipped for the Golden Lion, amid controversy, by Sacro GRA – an Italian documentary about a ring road that was favoured by the Italian-led jury of an Italian film festival. (There were dark mutterings of chauvinism from some critics, convinced that Taiwan had been robbed.)

Even for veterans remembering Tsai’s own Golden Lion (Vive L’Amour, 1994), Stray Dogs is an astonishing work: a tragicomedy about hope and destitution that mines poetry from penury and finds a fairytale incandescence in the mouldering mazes of urban decay.

The man in the 14-minute shot is a homeless father of two, played by Lee Kang-sheng, who has starred in all of Tsai’s films. Lee’s character is a “human billboard”, one of those hapless pittance-earners who, in Taipei, stand for hours holding up advertising signs for apartment rentals. A homeless man advertising homes.

“I started seeing these people 10 years ago,” Tsai explains. “I started wondering, what are their lives like? Where do they live? How do they go to the toilet?” (On screen we get a graphic answer, a minute-long close shot of the hero urinating in a bamboo scrubland.)

The marvel of Stray Dogs is that there is not an iota of miserabilism, or indeed message-mongering. The filmmaker’s fans will know this already. They will have seen The River (1997), The Hole (1998), Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003) and other films that by a sleight of art special to Tsai combine portraits of despair with chiaroscuro-rich visuals, seriocomical surrealism and a Beckettian flair for making structurelessness – stories with no immediately discernible shape or logic – its own structure.

The biggest magic trick is to make audiences love inaction: inaction that is enhanced, in Stray Dogs and other Tsai works, by rain and ruined buildings. This is the alchemy – native to the art of photography itself – of turning negatives to positives.

“Our cities are changing all the time. It is as if we are living in a giant building site. I never avoid these places in my films. They remind us of what we are losing. They have an emotional appeal, as if they are characters themselves with their own stories to tell. The painting I found in the building we use in Stray Dogs – a giant graffito depicting an idyllic pastoral landscape of stream and distant forest – was one we actually came upon, by a man who goes about painting these scenes in city ruins.”

The painting becomes the anchoring paradox of the film: an earthly heaven enshrined in an urban hovel. It’s what the characters stare at, unseen, in the 14-minute shot. At the end the painting is gazed at again by Lee Kang-sheng’s protagonist. When I venture that there seems to be an echo of John Wayne and The Searchers in that valedictory image and the actor’s pose, the director laughs the idea away. He even fleetingly mimics the Wayne stance (not easy to do when sitting down).

Who and what were Tsai’s influences when he started out? What films and film-makers made an impression on a Malaysian-born youngster, brought to Taiwan by his Chinese parents and flung into a semi-alien culture with few windows to the outside world and its cinema?

“Taiwan was beginning to open up culturally when I came,” he says. “We began to see outside cinema, especially European. Fellini, Bergman. Fassbinder. They were big influences. And also old Chinese cinema, which I am still interested in.”

At the very outset of his career Tsai found his ideal actor. He discovered the boyishly handsome Lee working in an amusement arcade. He cast him in his first feature and every one that followed. I venture to Tsai that one reason Stray Dogs works so well is that his star – in early films more decorative than expressive – seems now to have become a weather system of emotions. The actor’s ever-changing face mesmerises us during that 14-minute shot.

“Lee Kang-sheng and I have worked together and lived together for many years. He knows what I want and we each know what the other is thinking. It all comes from himself; I’m just there letting it happen. I don’t want acting. I want the real, whatever that is, and however long it may take to find. In a certain sense what I’m trying to do is give back freedom and reality to the actor.”

Sometimes, as in the 14-minute shot, that can result in a challenge to the audience’s patience?

Tsai laughs. “When I showed my second film Vive L’Amour in Singapore, it was in a 1,500-seater cinema and 500 people walked out. Nine years later, when I showed Goodbye Dragon Inn, no one walked out. Audiences get used to me; they start to understand to what I am trying to do.”

Does Tsai feel his work belongs in any broadly defined “Taiwanese cinema”? A decade or so ago, his early features converged with the work of older directors busy establishing the country’s reputation (Hou Hsiao-Hsien with City of Sadness, Edward Yang with A One and a Two), and Taiwan seemed a major force in east Asian movie culture.

“It was very free. I think that defined our cinema. It didn’t care about the market. It was a cinema of auteurs. There was no common style, just this freedom of creation. You look at Hou Hsiao-hsien or Edward Yang and they’re quite different from each other. You look at me and I’m quite different. I think there has been something very precious about these past 20 years. You have to liberate yourself from the market and from political influences and other influences. You have to be yourself.

“I love to make films about marginal people, because they are a part of my life and a part of what I am.”

Comments