Welcome to Jamshedpur, India’s steel citadel

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Compared with the tumult of most Indian cities, Jamshedpur seems like something from a fairy tale. Its streets are clean and tree-lined. Traffic is orderly. Residents boast of fine schools and lazy afternoons on the golf course. And the city’s centrepiece, looming over the surrounding streets like the castles in a children’s storybook, is India’s first, and still largest, steel mill.

The complex is vast, with dozens of buildings and belching chimneys making up one of the world’s most cost-efficient steel facilities, producing up to 10m tonnes a year for Tata Steel, the metals arm of the country’s biggest conglomerate. Yet it is the surrounding city that is perhaps more remarkable, given Jamshedpur’s place as India’s most successful industrial town.

Founded in 1907, central Jamshedpur, situated about 200km west of Kolkata, houses around 800,000 people, for whom Tata is a mixture of dominant employer and benevolent despot. The company has only 20,000 staff, but provides an array of services to all residents, from road-building to water treatment.

The results are impressive. Jamshedpur’s neat dual carriageways are free of pot-holes. Power cuts are unheard of. Uniquely for a big Indian city, it is safe to drink water from the tap. In many ways, the city provides a glimpse of what India might have looked like, had its government been as efficient as China’s.

These achievements are all the more remarkable given Jamshedpur’s location: Jharkhand, a state with bountiful mineral deposits but dire development statistics and an occasional Maoist insurgency. “Jamshedpur is like an oasis in that part of the world, a beacon in eastern India,” says Ishaat Hussain, former finance director at Tata Sons, the conglomerate’s holding company.

Most of Tata Steel’s top brass live in the city at some point; Hussain recalls fondly his time there in the mid-1980s. Since then, Tata has become a global giant, pulling off an array of big acquisitions, including the $13bn purchase of Anglo-Dutch steel group Corus in 2007. Even so, Jamshedpur remains at the heart of its steel business, and carries weighty symbolism for company and country alike. “This city has a very singular place in the history of industrial India,” Hussain says. “The history of Tata and Jamshedpur cannot be separated.”

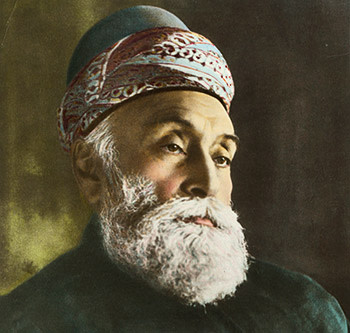

Jamshedpur takes its name from Jamsetji Tata, the conglomerate’s founder, whose bearded face stares out sternly from statues in the city’s many public parks (Jamshed is a transliteration variant, “pur” means city , and the “ji” suffix is an honorific). In 1867, the young industrialist is said to have attended a lecture in Manchester in which Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle praised the virtues of steelmaking.

Tata

Founded 1868

Diversified conglomerate

Tata is India’s oldest, best-known and largest conglomerate, with revenues of $109bn last year. Based in Mumbai, the group comprises more than 100 companies covering an eclectic range of sectors, from watchmaking and sugar to chemicals and software development, taking in an array of global brands such as UK-based carmaker Jaguar Land Rover and Tetley Tea. However, the company’s heritage is firmly in industrial concerns, from textiles to iron and steel — the last of which prompted founder Jamsetji Tata to establish Jamshedpur as the home for India’s first steel plant in the early 20th century.

Inspired, Jamsetji Tata spent decades trying to rustle up funds, land and expertise to put up a plant in India, jotting down his plans in a special scrapbook. A trip to Pittsburgh in 1902 — then the world’s leading steel city — helped his scheme take shape. Five years later, a Tata team finally found the ideal plot of land, nestled between two rivers and blessed with access to plentiful water, coal and iron ore.

Much of Jamshedpur’s subsequent success stems from its early design. India’s industrial pioneers often built homes and schools for their workers. But Tata took these commitments more seriously than most, inviting British socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb to help plan out the city’s social services. “Be sure to lay wide streets planted with shady trees [and] space for lawns,” he wrote. “Reserve large areas for football, hockey and parks. Earmark areas for Hindu temples, Mohammedan mosques and Christian churches.”

The man now responsible for delivering this vision is Sunil Bhaskaran, a veteran Tata Steel executive with a bushy black moustache and jolly demeanour. His title is vice-president of corporate services, but the job is more akin to an American mayor, with $30m to spend each year on the city’s upkeep. Bhaskaran laughs off the mayoral comparison, but talks animatedly about plans for road widening and sewerage treatment, all to be undertaken by Jusco, the city management company Tata spun out in 2004.

A round-the-clock call centre handles resident complaints — regular reports landing on Bhaskaran’s desk — while the company is involved in everything from rounding up stray dogs to controlling mosquito-borne diseases. “In order to look after 20,000 of our employees, we are catering to 800,000. I don’t think many companies would do that,” he says.

Tata’s approach mixes charity with clear corporate self-interest. All that spending buys plenty of goodwill. Jamshedpur’s plant has doubled capacity over the past decade, while its workforce has fallen from a peak of 80,000 — a feat achieved without industrial unrest. Yet the company’s sense of social obligation seems genuine, with projects funnelling cash to myriad local charities and tribal groups. Sport looms large, too, with a Tata-funded athletics stadium in the middle of town, as well as a trio of lush golf courses open to all residents.

“For some young engineer to come here and learn golf from a national champion at a throwaway rate, that is unimaginable in other cities,” Bhaskaran says. The city’s sporting culture has even attracted celebrity residents, such as Bachendri Pal, the first Indian woman to conquer Mount Everest, who now runs a training centre. “I climbed Everest in 1984, and Tata supported me,” she says. “What they have done since to support adventure sports here is very unusual for a corporate house.”

Still, not everyone is happy. Some residents complain Tata’s stewardship has created a cosy enclave for steel executives but little of the dynamism that characterises India’s big cities. “They maintained it well, no doubt, but they didn’t allow it to grow,” says Rajeev Dugal, a local hotelier. “When a town evolves you have malls, eating places, movie theatres. But Jamshedpur has none of these.”

Ryan D’Costa, the founder of Brubeck Bakery, a rare fashionable café, concurs. “All of my friends have left — there isn’t much for young people here,” he says.

Beyond Tata’s central citadel lies a tougher problem: Jamshedpur’s sprawling outer city, run by regular municipal authorities, over which Tata has no control. Add in this area and the population jumps to 1.4m. Outside, development is chaotic, with frequent power cuts and dirty drinking water. “This causes resentment, no question,” Bhaskaran says. Tata’s executives complain of frequent incursions to steal electricity or build illegal housing.

At a deeper level, this division leaves the company facing something of paradox. Over the years it has fought occasional attempts by local politicians to hand its powers to a regular city council. In this, it has been strongly backed by residents in two referendums.

Hershey

Founded 1894

Confectionery

Milton Hershey set up a candy shop in 1876 in Philadelphia, only to see it go bust within six years. Unperturbed, he launched a far more successful business in a nearby town making caramels, selling it for $1m in 1900. He used the proceeds to expand his Hershey Chocolate Company, set up six years earlier to produce coatings for the caramels. He built a new plant in his home town, which would soon be renamed Hershey and continues to justify its motto as “the sweetest place on earth”.

“Letting the politicians run it would be a prelude to ruining it,” says Jamshed Irani, a former Tata managing director who has retired to the city. Yet neither is Tata willing to bear the heavy costs of providing its services to the rest of the city, as is often asked to do, viewing it as one long-term charitable headache the company could do without. Its refusal to risk this means the divisions between the two sides of India’s steel city are only likely to grow.

This need not be a fundamental threat. In common with other corporate towns, Jamshedpur is likely to prosper as long as Tata Steel itself continues to expand in India, which seems likely, given the country’s expected rapid future growth.

For those within Tata who view the city with a mixture of pride and nostalgia, there is perhaps a greater worry — that Tata Steel’s continuing international expansion might in time see the company outgrow the city that once provided its heart. “It has a great sentimental position in the Tata psyche,” says Ishaat Hussain. “Perhaps that is dwindling now that Tata is such a global operation. But Jamshedpur will always be something special to us.”

Letter in response to this report:

FT could be more critical of a company town / From Andrew Sanchez

Comments