Our pick of Peter Aspden’s columns

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Read FT arts writer Peter Aspden…

…on cultural diplomacy

…on Miley Cyrus

…on urban art

…on dissent

…on the dark side of British culture

…on how art tells the truth

…on satire

…on ruin lust

…on damnation

…on bringing back the 1970s

————————————————————————————-

A diplomatic figleaf for the Parthenon Marbles

There is nowhere quite like a temple of high culture in which to make friends and influence people. In 2000, the soon-to-be Russian president Vladimir Putin nestled up to Tony Blair when the then British prime minister visited the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. The two men stopped in front of a portrait of the Duke of Wellington in full military dress, extravagantly decorated with Russian orders. “You see,” said Putin to Blair, “when we are together, all is well in Europe.”

Putin’s remark, I am guessing, was delivered with steely irony. But something about museums draws out the dew in the eyes of those who are otherwise stuck in the rancid mud of realpolitik. That can be a touching thing. We all need to escape from the world’s nastiness now and again.

The story of Putin and Blair was told to me by Mikhail Piotrovsky, director of the Hermitage, who had his own special museum moment last week with the announcement that his institution had received, on loan, a statue of a river god that is part of the British Museum’s display of the Parthenon Marbles. It is the first time the museum has allowed an item from Lord Elgin’s disgracefully acquired collection to leave the UK.

The loan has been hailed as the latest example of “cultural diplomacy”. Relations between the UK and Russia are fragile. The director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, is using the statue of the river god Ilissos as a “stone ambassador of the Greek Golden Age” so that the Russian people might be seduced into a newfound appreciation of ancient Greece’s humanistic values. And then what?

MacGregor, to his credit, disdains any phrase that uses the word “diplomacy” to describe what he does. He is too smart to fall for the intellectual conceit that the shuttling of pieces of stone from one country to another for a few weeks can have any material effect on things that matter.

The misapplied label was first employed when the museum put on two wonderful exhibitions in London, on ancient Persia and on the rule of Shah Abbas, at a time when UK-Iranian diplomatic relations were tipping from chilly to frostbitten. As a follow-up, it sent the Cyrus Cylinder, one of the first ever declarations of human rights, to Tehran. There is a press picture of the former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad, looking quizzically at the cylinder in its glass case. Space prevents me from listing the examples of his evident misunderstanding of its significance and meaning.

…

Cultural diplomacy: there are two ways of looking at it. One recounts the fiendishly clever way that the world’s scholars are confronting tyrannical regimes by their erudite exchanges of quietly subversive material. The other view notes that unpalatable governments are becoming mightily effective at using art as integral parts of their public relations strategies. Abu Dhabi and Qatar are building some of the most spectacular new museums in the world, even as they treat their labourers with contempt. Free-speech-fearing China holds art fairs and biennales. These governments are the true cultural diplomats of the world: they exploit, rather than fear, the civilising sheen of great art. Look how cultured we are, they say. Don’t look too closely at our factories or police cells, come into our museums instead.

The otherwise worthy journey of Ilissos to Russia would not merit any further comment were the statue not part of the most controversial group of art works of our time. To Russia With Love is as near as the British Museum gets to lifting an elegant middle finger to Greece, which has long harboured hopes of the Marbles’ return.

In choosing the figure of River Ilissos, MacGregor says, we are taken back to the time of Socrates, who conversed with Phaedrus in the “cool shade of the plane trees that grew along its banks, discussing the value of beauty and the morality of love”. It is a flattering view of the eccentric philosopher, who famously cared not a jot for his polis, preferring to peddle his pedantry and icy logic to anyone who would listen. While Jesus wept for Jerusalem, wrote the Platonist scholar Gregory Vlastos, “Socrates never shed a tear for Athens.” No wonder he is a hero to the British Museum.

MacGregor eschews most of the arguments proffered against the Greek case for the Marbles’ return — he knows them to be clapped out. Instead, he puts forward his eloquent vision of the “universal museum”. It is a vision which insists, as the classicist Joan Breton Connelly says in her outstanding The Parthenon Enigma, on “a placeless universality for cultural objects [which] ignores the complexities of financial interests attending ownership, imbalances of power among nations, and class inequality that results in the cultural heritage of the poor remaining ever under the control of the rich.”

Her view is widely shared. Greece is slowly winning the argument. I have no doubt that the Parthenon Marbles will be returned to Greece, perhaps not in our lifetimes, but soon enough. There are, not least, some very powerful advocates in support of its case. Here is one of them — no, not George Clooney — speaking on a visit he made to Athens in 2001:

“Various conquerors attempted to remove and appropriate parts of the monument, [which is] bad, on the one hand, and an indirect recognition of the ancient magnificence of Hellenic civilisation on the other. Despite the problems, the Greeks are trying to restore that which belongs not only to them but also to all of humanity. We shall be at your side in your efforts.”

You guessed it, Vladimir Putin. Never mind Greeks bearing gifts: keep an eye on those Aeroflot flights to Athens. There is a river god on the run and he is yearning for some sun.

Letter in response to this column:

The origins of DC’s teams matter to baseball fans / From Richard Schulman

————————————————————————————-

Growing pains

This column has so far scrupulously declined to chart the peril-laden voyage that marks the passing into adulthood of Miley Cyrus. It has been a rambunctious affair, her every hormonal surge seemingly designed to capture the attention of the world’s media outlets.

There has been controversy along the way. Outraged American moms’ groups are unhappy that girlish charm should be so vulgarly traduced by womanly cravings in public. Best for those awkward transformations to take place behind closed doors, they say. Role models should stick to their roles, or disappear from view. Miley refuses to do either. She is rude, and wants you to know it.

Now, in a move that forces her on to the agenda of these august pages, she is trying out as a contemporary artist. Her debut show, Dirty Hippie, is a collection of erotic sculptures that are crafted from the everyday materials that surround her stellar life. The garishly-coloured plastic goods – were this a serious art review, we would be compelled to call them “found objects” – include a vibrator, a marijuana joint, a pineapple and some party hats, assembled with a contemptuous dismissal of conventional artmaking.

The works were first seen at a fashion show during New York Fashion Week, and are currently on display at the city offices of V magazine, to which Cyrus has given an exclusive interview. This is what she has to say about her art: “This seems so fucking lame to say but I feel like my art became kind of a metaphor – an example of my life . . . I hated 2014 because everything that could go wrong kept going wrong. Being in the hospital, my dog dying . . . Everything just kept shitting on me and shitting on me.

“So then I started taking all of those shit things and making them good, and being like, I’m using it. My brother and my friends all said that’s what they felt I was doing. So, that’s how I started making art. I had a bunch of fucking junk and shit, and so instead of letting it be junk and shit, I turned it into something that made me happy.”

The singer also reveals that the pineapple was chosen for its well-known erotic qualities (you either know or you don’t; if you are in an American moms’ group, don’t ask), and says she has started to dabble in art to find some intellectual credibility. “That’s my goal in life: to not die a pop pop dumb dumb.”

Now I haven’t seen the show, and can only say that the photographs of the pieces make them look wretched and a bit sad. But there are two striking things to note about Dirty Hippie. The first is that Cyrus, who is not formally trained and does not display a conspicuous knowledge of art history, is speaking in a perfectly conventional way about her art.

She has assembled objects from her daily travels with a view to finding a transcendent quality in them, and uses the exercise as catharsis. Nothing strange here. Indeed, we may argue that the wretchedness and sadness of the whole affair is, in fact, an acute commentary on the hellishness of Miley Cyrus-level celebrity.

She hints as much herself: “They say money can’t buy happiness and it’s totally true. Money can buy you a bunch of shit to glue to a bunch of other shit that will make you happy, but besides that, there’s no more happiness.”

…

The second theme to emerge from the show is the confirmation that contemporary art has definitively replaced rock’n’roll as the go-to art form for young people with no particular talent, but plenty of attitude, to express themselves. From its origins in the 1950s to the burning comet that was punk, rock’n’roll inspired energetic imitators who stood in front of mirrors and said to themselves: “I can do that!”

Nowadays, everyone wants to be a contemporary artist. It pays well and requires apparently little effort. It is an art form of its time. Where rock’n’roll was the primal scream of nonconformity, contemporary art is the deft assemblage of the millions of pointless objects and images that zip around the world more quickly than we can properly process.

If we needed any proof of this cultural shift, on the very day of the Miley Cyrus show opening, that ageing silverback of popular culture, Keith Richards, came on to the BBC’s Today programme to talk about his new book, Gus & Me: The Story of my Granddad and My First Guitar. He was softly-spoken and rather charming.

The 70-year-old guitarist explained the motivation behind the book: “I suddenly thought about grandfathers, and the relationship between grandchildren and grandfathers, and what a great thing it can be if it can happen.” Spookily, his granddaughter Ella was preparing for her debut as a model for New York Fashion Week, ready to plunge into the world of Miley Cyrus and her erotic pineapples.

“This growing up isn’t so bad after all,” said the Rolling Stone of the energising effect of his newfound vocation. Tell that to Miley. It would be pop pop dumb dumb for her not to listen.

————————————————————————————-

Urban, edgy, lucrative

I have a rendezvous with Pure Evil, one of the most prominent names of the thriving street art scene, at his own gallery in Shoreditch. I am expecting a journey into the heart of darkness. But British contemporary art is nothing if not noted for its ironic touches, and Evil – real name Charles Uzzell-Edwards – is of course a genial, well-spoken, middle-aged man who instantly asks me out for a drink up the road.

So far, so wholesome. As we leave the gallery, he does a double take. He points to an abandoned car park across the road, the surrounding walls of which are festooned with elaborate street paintings. One of them is missing, Evil tells me. A Frankenstein’s head that was there a few hours ago has disappeared: one of the walls has been demolished. A boutique hotel will shortly be built on the site, he says. Frankenstein is an early victim. The rest of the art will follow. Here today, betrayed tomorrow.

And yet urban art has never been in ruder health, its ephemeral zest turned into something more long-lasting, and commercially viable. Banksy, the movement’s flag-bearer, has become an auction-house favourite. And Pure Evil himself, quite apart from owning two galleries on the same street in Shoreditch, is becoming an unlikely interloper in the traditional art establishment.

He was recently commissioned by Royal Doulton to produce a set of plates for the company. “The limited edition of large plates reinvigorates the concept of using ceramic as an interior design art form,” gushes its promotional literature. “These are pieces to be displayed and are bound to create conversation!” Evil’s enthusiasm is drier in tone: “I really liked the idea of appearing on Antiques Roadshow one day.”

From the contrived drama of his moniker to his easy way with a paradox, Pure Evil symbolises much that is good, bad or uncertain about the art world today. A descendant of Sir Thomas More and son of an artist, Uzzell-Edwards left Britain, or “the ruins of Thatcher’s Britain”, as he likes to put it, in 1990 to design a streetwear clothing label and make electronic music in San Francisco. He returned to the ruins of the old world a decade later, just as the British street art scene was taking off, and joined it, spraying his signature bunny rabbits all over town and reviving a childhood signature.

He enjoyed the movement’s playful nature, he says, pointing to an early print, “Sergeant Peppers Lonely Hearts Bastards”, which replaced the randomly chosen figures in Peter Blake’s original artwork with an assortment of historical miscreants (the faces of The Beatles are substituted by Lenin, Pol Pot, Stalin and Hitler). “I read somewhere that John Lennon always wanted to put Hitler on the cover, but wasn’t allowed to,” he says, claiming provenance with a rebellious spirit. He opened his first Pure Evil gallery in 2007, initially as a pop-up, and then as a permanent fixture of the burgeoning east London art scene. He makes a joke about his “stature as an artist”, supplying the ironic quotation marks himself: I flip them back to him, wondering if he ever worried that his commercial activities compromised his “integrity as an artist”.

“Not when you have a family and a baby and a constant supply of nappies to pay for,” he replies. “I am not going to worry about a 19-year-old complaining that I am a sellout.”

…

He tells me two anecdotes which seem to sum up the dilemma that urban art faces as it gains acceptance. An acquaintance of his was recently asked to design a graffiti-strewn background to a video game to emphasise its sinister environment; while at the same time, estate agents were photographing street art to promote the “edginess” of up and coming neighbourhoods.

There is no greater act of pusillanimous surrender for art, I say, though not quite in those words, than to be promoted by estate agents. Evil admits that the genre is at a crossroads, in danger of losing its authenticity. “The battle is to take it back,” he says. A recent trip to South America restored his faith. He watched passers-by giving thumbs-up signs to a bowdlerised version of “Guernica” in Chile. “That’s so much more important than 4,000 ‘likes’ in Shoreditch.”

There are, in the meantime, signs that street artists are becoming more ambitious in their scope, keener to align themselves with the centuries-old subjects of traditional art forms. ALO is an Italian street artist whose new show at London’s Saatchi gallery is said to be “informed and influenced by …the German Expressionist movement, the raw simplicity and directness of art from Africa and the energy of Punk”. This is the language of the gallerist, rather than the spontaneous argot of the back alley.

The works of Pure Evil on display in his gallery, Warholesque prints of celebrities who are shedding trademark tears which often flow off the canvas all the way down to the floor, have a certain emotional resonance of their own. “Why are they all crying?” I ask him as we say our goodbyes. “They are remembering relationships,” he replies. “Bad relationships, that you don’t realise are bad at the time, and then you get out of them …”

Pure evil? Pure schmaltz.

————————————————————————————-

Instant icons of dissent

Mounting a protest can be a tricky business. I remember reporting, in the 1980s, on a campaign by university lecturers to improve their conditions of work. Their very erudition may have hampered their cause: the stirring slogan they chose to win round the masses was “Rectify the Anomaly!”

I can still picture the none-too-prepossessing young man holding his placard by the side of the A4, pulling the deadened gazes of weary commuters driving out of London towards his convoluted message. Marxist revolution was surely around the corner.

But it didn’t turn out that way. The political establishment managed to survive that devastating threat to its authority. The anomaly, whatever it was, lived on. It would be nice to think that there is a stash of “Rectify” T-shirts to be found in the basement of a former polytechnic somewhere, a legacy to that bone-rattling call to arms.

It would have made a fine addition to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new exhibition Disobedient Objects, which opens today. The show illustrates how the battle for hearts and minds has evolved over the past quarter of a century, and how the once-simplistic art of social protest has acquired its own refinements and sophistication as it has moved with the times.

It begins in the late 1970s, a time that many would consider to be well past the golden age of protest. The handsome Che Guevara posters, the students placing flowers inside the guns of soldiers, the pregnant lyrics of chart-topping pop songs (“Call out the instigators, because there’s something in the air”) – all these pivotal cultural moments belonged to the previous decade. The 1970s, widely regarded as a hangover decade, was when protest discovered its limits, rather than celebrating its potential.

And yet whatever it lost in directness and militancy, it was beginning to gain in practical wisdom. The artists and designers of the post-1960s sensibility employed a richer palette of tone than their predecessors. They used drama: the striking life-sized puppets of the US’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, promoting democratic culture and bread-baking as antidotes to high capitalism.

They appropriated high art: China’s “Goddess of Democracy”, a torch-bearing statuette, was based not – as commonly thought – on the Statue of Liberty but on the Soviet sculpture “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman”. The original “Goddess” was constructed, and then destroyed by a tank, in Tiananmen Square; the cheap copy is to be found in the home of many a dissident of the regime. Samizdat kitsch or revolutionary totem?

Protests against baton-wielding police forces gained poignancy when students began to use shields that were painted as book covers, a tactic first seen in Italy in the last decade. It seemed, as police moved against them, that the forces of law and order were clubbing the life out of Boccaccio and Dante. This was protest designed to be observed through technology’s rapid dissemination of images. Social media created instant icons, and here were political malcontents moving as sure-footedly as any high-flying brand consultant.

In Berlin and Barcelona, demonstrators used giant cube-shaped “cobblestone” inflatables, which they would float towards the police lines. The authorities were faced with a conundrum of absurdity: did they pretend to ignore them, as they landed haplessly among their ranks? Or did they bounce them back to the demonstrators, farcically turning a serious engagement into a game of beach volleyball?

…

Humour has become a powerful weapon: dissident acts are designed to raise a wry smile rather than a howl of outrage. In the US, a graffiti-writing robot took the pain (and perhaps the fun?) out of spraying slogans on walls. Here, surely, was alternative culture’s counterpart to drone missiles, the double-edged critique deftly made.

Recent demonstrations in Britain, never a country to stray far from a joke, have seen withering epigrams on placards denouncing government spending cuts: “I wish my boyfriend was as dirty as your policies”, read one. In Russia, a rainbow-coloured placard reading, “We won’t give it [the Russian presidency] to Putin a third time” is replete with sexual innuendo.

These absurdist and ironic twists were all very well, I said to the V&A exhibition’s co-curators Catherine Flood and Gavin Grindon, but were they effective? Grindon believes that they symbolise a new realism about the limits of social protest.

“In the 1960s, there was a higher expectation of immediate change,” he said. “Now there is no less utopianism around, but there is a much stronger sense of having to be strategic.”

Protesters, in other words, are in it for the long haul. The explosive shows of dissent that shook the 1960s forced governments to turn their attention to issues such as race and gender. But it was the consolidation of those protests in the following decades that won the battles. Today, going viral is more important than going to the barricades. And the instigators need to be more artful than ever.

‘Disobedient Objects’, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, July 26-February 1 2015, vam.ac.uk

————————————————————————————-

Welcome to the empire club

Keen diplomatic observers will have noted and analysed the geopolitical ramifications of David Cameron’s present to Li Keqiang during the Chinese premier’s recent visit to London. The widely publicised gift, a shooting script of the first episode of Downton Abbey signed by the show’s creator, Julian Fellowes, was rich in subtext. It is, I suppose, just about possible that Li is simply a fan of the programme. But that seems preposterous. This is politics. There was some kind of power-game going on, have no doubt about that.

Here is what may have been intended. First, the simplest scenario: Cameron was proudly showing Li how life was during the final years of the golden age of the British Empire. All that gentility, those plush interiors, that hegemonic drive. Intimidation through costume drama: soft power at its finest.

But hold on to your teacups. We learn that it was Li, in fact, who expressed his admiration for the series, and even wished to visit its Hampshire location, Highclere Castle. How devilishly clever. A softly powerful serve returned with stinging topspin. This, Li says as he receives the epochal document from Cameron, is what you used to have. This was the high point of British life. How far you have fallen. Now you huddle around your television sets to watch Britain’s Got Talent. How does that feel? Li will doubtless have seen the most recent episode of Downton, set in 1923. Guess what is coming up in three years’ time? The General Strike, that’s what. It was all downhill from there.

But Cameron has followed his softly powerful serve with a neat volley. Yes, Britain used to be this great. It was good to have an empire. But you know what? All empires flounder. You may be feeling the rush of power right now, and feel like you can do anything you want (enter stage left: fleeting reference to human rights) but don’t for one moment think it is easy, or that it is going to last.

This, I think, was Cameron’s hidden message. But he might have gone further. Downton Abbey is all very well, but he could have really stretched the point of imperial decline with some further well-chosen gifts. The prime minister, steeped in popular culture, or at least Dark Side of the Moon, missed an opportunity. But here are some ideas for that perfect downer of a present for the future, the dark side of British culture:

1. Free tickets for the Monty Python’s Flying Circus reunion at the O2, Monty Python Live (Mostly), opening this week. Can there be anything more dispiriting than a bunch of ageing surrealists? Especially when they joke about only getting back together for the money, when it is clear they are (mostly) only getting back together for the money? Is there nobody young and funny and hungry left in the country?

2. Free tickets to see a British film. Of course British technicians and actors are admired the world over. But the general intention of British movies is to make us depressed. We know this because every few months there is an article in the press headlined: “British Films are Depressing”. The latest was by the actor Toby Stephens, writing in March. “We need to stop trying to do the same movies over and over: the gangsters and football violence,” he wrote. Not to mention the kitchen-sink realism, the homely working-class comedies, and the upper-class-twit farces. A personal favourite is Rita, Sue and Bob Too, the ugliest film of all time.

3. The CD, or better still the DVD, of Let It Be, The Beatles’ final album. This marked the terminal decline of Britain’s last golden cultural age. Mop-tops mired in mutual contempt, antsy arguments, bad songs. Pop music, after one or two sleepy detours (see Dark Side of the Moon), never recovered.

4. Free tickets to a VVIP preview of any art fair. Watch the hyper-rich eschew the joys of handbag shopping for an hour or two, and spend millions on paintings of dots instead. Watch out, Premier Li, it’s coming your way, faster than you think.

5. An original manuscript of a devastating rock lyric. This week, the handwritten words to Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” sold for more than $2m at Sotheby’s. The song is a succinct snapshot of life in the western world (“Now you don’t talk so loud,/ Now you don’t seem so proud,/ About having to be scrounging your next meal”), but the British can do better. Here’s a coruscating analysis of social immobility: “All that rugby puts hairs on your chest,/ What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?” That’s from the Jam’s “Eton Rifles”, a personal favourite of the prime minister, and why wouldn’t it be?

In the Global Times, a Chinese tabloid affiliated to the People’s Daily, readers were urged, in the wake of Li’s visit, to take pity on the “old declining empire” that is Great Britain. “Britain’s national strength cannot be placed in the same rank as China now,” it thundered, “a truth difficult to accept for some Britons who want to stress their nobility.”

You see, Mr Cameron, they fell for it. Li Keqiang, in the meantime, may be having deeper thoughts: do I really want to have an empire at all?

————————————————————————————-

So much for cultural openness

Abraham Oghobase is a Nigerian photographer in his mid-thirties whose witty and original pictures are gaining him an international reputation. His work is based on the documentary tradition, but it is given a distancing quality by the artist’s own presence in the photograph. This combination of reportage and performance art,

while not unique, compellingly adds layers of complication to otherwise straightforward depictions of the socio-economic tensions of his homeland.

In a recent series of work, he shows walls of buildings in the centre of Lagos that have been filled with scrawled slogans advertising various services. Then he poses in front of them in gestures that are amusing, mysterious or ironic. One such advertisement – “Sexual Disease/Fast Ejaculation/ Weak Erection”, followed by a telephone number – shows Oghobase at the side of the frame, curled up asleep. Another, “Piano Lesson”, has the artist playing what looks like the solemn notes of a sonata in the foreground.

Some months ago, these very same pictures were shortlisted by the jury of the Prix Pictet for photography (of which I was a member), which addresses the theme of environmental sustainability, for this year’s prize. Swiss bank Pictet gives SFr100,000 (£66,200) to the winning artist, and the competition regularly attracts the world’s most distinguished photographers. The inclusion of Oghobase would have been a source of pride for him, and his country’s culture.

So it is sad to report that he never made it to the event’s prize-giving ceremony, which took place on Wednesday at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. If he had won – and it is not to betray any confidences to say that his work was highly praised by all the judges – he would have been absent from what would surely have been the crowning moment of his career so far. In the end, the prize went to the veteran German photographer Michael Schmidt.

A couple of weeks ago, it was revealed to the judges that Oghobase had been refused a visa to travel to London for the ceremony. As is customary in these cases, no reason was given for the refusal. Appeals from the artist’s lawyers were turned down. A note to Britain’s home secretary from the Prix Pictet committee seeking explanation was simply ignored.

This is a sorry state of affairs for a country that professes to be in the vanguard of cultural openness, and a city that considers itself to be the creative capital of the world. Oghobase has travelled widely and is becoming a familiar figure in the world of photography. If the British government has something incriminating on him, perhaps it had best share it: the artist moves freely throughout Europe and the US (he was in Seattle during a recent telephone conversation with the Pictet secretariat).

Of course, recent news of the terrorist attacks in Nigeria, subjected to the amplifying effects of 24-hour news coverage, has been mostly distressing. Does this just prompt a knee-jerk reaction from nervous border control agencies? It is not, to say the least, beyond the realms of possibility. What are their decisions based on? In this instance, we shall never know.

Yet it is precisely in situations such as these when our so-called respect for culture and its various practitioners should kick in. Government and politics are, even in mature western democracies, happily clandestine affairs. Secrecy develops its own logic, its own dark momentum. It becomes a default mode of behaviour. In some cases it is necessary. In most it is not.

The practice of art is the opposite. It is transparent, expressive and bold. It is also committed to telling truths, even if they prove to be unpalatable to those in authority. This can make life uncomfortable for governments, although this, too, can also be overstated: the ability of totalitarian regimes to absorb dissent in today’s climate shows great sophistication, and a shrewd understanding of how art can be diverted or co-opted, where it used to be suppressed.

…

The theme of this year’s Prix Pictet was consumption, and the photographers who participated showed a wide variety of strategies in dealing with their subject. The works of the shortlisted artists are currently on display at the V&A, and form a trenchant, not always predictable, critique of a world that is grievously unbalanced in so many ways.

Lebensmittel, the winning series of photographs by Schmidt, is a measured look at the way food is processed and prepared for our twisted consumption. It makes its points with unruffled insistence.

Oghobase’s work, by contrast, is exuberant and a little wild. It conveys the desperation of a society in which every act of consumption is something that can be bargained for on every street corner, in bright, bold letters, and in whispered telephone conversations.

If we want to understand what is happening in Nigeria today, we need to listen to that country’s young and intelligent voices. News reporters do a fine job under the stress of sharp deadlines. Politicians – some of them – are articulate, but inevitably compromised by circumstance. It is artists who hint at deeper truths. We have lost an opportunity to learn from one of them, and we don’t even know why.

Prix Pictet at the V&A, Porter Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, until June 14. prixpictet.com

————————————————————————————-

Satire that has no sting

Some days ago, Tony Hall, director-general of the BBC, welcomed journalists, well-wishers and a sprinkling of celebrities to Broadcasting House to unveil the corporation’s new plans to cover the arts, and to put the public “in the front row of British culture”. He referred to the building’s postcode – W1A – which raised a titter of recognition. That, we all knew, is the name of a new BBC2 comedy series, a follow-up to the well-received Twenty Twelve, and transfers its satirical aim from the organisers of London’s Olympic Games to the management of the corporation itself.

No one who has had any experience of television, newspapers, advertising, marketing, social media, branding, spinning or just plain working in an office stuffed with incompetents whose ambition overreaches their abilities will fail to recognise the gags here. To give the show some extra grounding in real life, there are cameos from well-known personalities: Clare Balding, Carol Vorderman. There are rumours that Hall himself will appear in a future episode.

I dearly hope not. This is satire that goes too far. Not in the direction of the controversy, exaggeration and poor taste that are its natural roaming ground. W1A goes the opposite way, towards complacency, complicity and all-round smugness. It is officially sanctioned satire, the humour co-opted by its targets to neutralise its sting. It is hard to see it as anything other than a deflection mechanism, fending off the BBC’s critics with some good, old-fashioned self-deprecation. Look how we laugh at ourselves! Aren’t these people silly? (Sub-text: we are much more sensible than that, otherwise we would not be able to see the joke.)

Floppy satire is bad news. In the current New Yorker, there is an excellent essay from that magazine’s television critic Emily Nussbaum on the US sitcom All in the Family. Norman Lear’s refashioning of Britain’s Till Death Us Do Part was considered so incendiary by the networks that it was preceded by a kind of health warning when it was first aired in 1971: “All in the Family …seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show – in a mature fashion – just how absurd they are.”

You can smell the fear. Lear’s Alf Garnett figure was Archie Bunker, played by Carroll O’Connor, who railed against the “coons”, “spics” and “fags” who were making his neighbourhood, and his world, an uncomfortable place. As with Garnett, the issues he addressed were very much alive in the polity at large. And as with Till Death Us Do Part, the audience of All in the Family was split between those who – “in a mature fashion” – got the joke, and those who got the joke but also thought that the programme’s anti-hero actually talked a lot of sense.

…

It is unfair to compare the pungent joke-making of a programme conceived at a time of social turmoil with the soothing satire of W1A. But it is a reminder that comedy can be a remarkable force for ferreting out the blemishes of the society from which it springs. However impassioned your view on the BBC licence fee and the loony vocabulary of its managerial classes, they are not subjects that are comparable to the endemic racism and sexism of an age that is not so far behind us.

The positive spin on this is that we are so much better off these days that we don’t need our comedy to be vicious. The more pessimistic view is that the establishment has become expert in the co-option of its critics. Satire has been sanitised. Even the most monstrous sitcom characters – Malcolm Tucker, the malevolent spin-doctor from Armando Iannucci’s The Thick of It, for example – are absorbed by the political mainstream as weirdly loveable mavericks.

Which brings us back to the BBC, and the trumpeting of its “greatest commitment to the arts for a generation”, in Hall’s words. Truth to tell, there was much about the event that was scarcely distinguishable from its self-referential sitcom, from the solemn announcements that separated us by our colour-coded wristbands, to a muted onstage interview between Alan Yentob and Gemma Arterton.

Perhaps the most satire-worthy moment was the announcement that a new “take” on Kenneth Clark’s famous series Civilisation was being commissioned “for the digital age”. Clark’s version was regarded as seminal high culture for the masses, and was seminally skewed. In comparing an African mask with the head of the Apollo of the Belvedere, he declared there was “[no] doubt that the Apollo embodies a higher state of civilisation than the mask”. The works showed that while the “Negro imagination” conjured a world of fear and darkness, the Hellenistic one luxuriated in one of “light and confidence”.

The conversations that steer our post-politically-correct age out of this thicket will be compelling to follow, and way beyond satire.

————————————————————————————-

The joy of archaeolatreia

When I was a child visiting relatives in Greece, there was a bus I always particularly wanted to catch into the centre of Athens, even though others went in exactly the same direction. The reason was that it sported the best destination ever on its front, stamped in solemn and portentous letters: AKADIMIA, or the Academy. I imagined, back then, that this was the way to Plato’s Academy, and that the bus journey would end amid the silver olive trees that constituted the original groves of academe, and the odd resonant piece of weather-beaten marble by the side of the road.

I was mistaken. The vehicle trudged into the centre of a city that had long ago forsaken olive trees for traffic lights, and it turned out that Plato’s school was actually in the opposite direction. I expressed my disillusionment, but was sharply reprimanded. I had succumbed to a common ailment, said my friends: archaeolatreia, or love of the ancient. Only this was not a healthy love, but an excessive one, a romanticisation of the past that ultimately stopped one from living in the present. We indulge in the perceived glories of ancient times at our peril, I was warned. They weigh heavily, and rarely help us move forward with any sense of purpose.

At Tate Britain’s smart new exhibition Ruin Lust, archaeolatreia is given free rein. Indeed it encounters a sister term which gives the show its title: the German Ruinenlust, adopted in the 1950s by the author Rose Macaulay to describe the obsessive regard for the architectural debris of the past, finding in the fallen columns and crumbling façades of past civilisations a sense of hubris and cosmic pessimism that remains fashionable to this day.

The exhibition’s co-curator, Brian Dillon, rightly explains that the reverence for the ruin disguises a multitude of intellectual impulses: “a reminder of the universal reality of collapse and rot . . . the symbol of a certain melancholic or maundering state of mind . . . a memorial to the fallen of an ancient or recent war . . . a desolate playground in whose cracked and weed-infested precincts we have space and time to imagine a future”.

The taste for ruins, he says, is a modern one, catching fire during the Enlightenment, a time that found the idea of physical decay both uncomfortable and inspiring at the same time. He quotes the German poet Friedrich Schlegel: “Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many works of the moderns are fragments at the time of their origin.” Things that last forever turn into kitsch: how much more satisfying for the imagination to witness the effects of destruction, and from there build anew.

But the cult of the ruin reached extraordinary lengths some years later, when Sir John Soane, not long after designing his architectural masterpiece, the Bank of England, in the early 19th century, himself commissioned from the artist Joseph Gandy a bird’s-eye painting which depicted the bank as a future wreck.

There was no stopping the morbid fascination with decay now: landscape designers built ruin-lust follies in gardens, so confident of the resilience of the British empire that they felt safe enough to make visual jokes about its collapse and the effects on the “ruined” city of London. It was at once playful and arrogant. Soane even had the effrontery to write a narrative, Crude Hints towards an History of my House, in which he imagined a future archaeologist inspecting the fragments of his home, wondering if they were the remains of a monastery, a Roman temple, a magician’s lair or the house of a persecuted artist.

…

This was the fantastical phase of ruin lust, powered by aesthetic fascination – all that creeping vegetation and startling chiaroscuro – and indulged by a narcissistic society. But we live with the legacy of the weapons of mass destruction that tore their way through the 20th century, and the joke is largely lost on us. Thanks to mortars, mines and all the rest, a neighbourhood row can turn into the most spectacular of conflagrations. We are never far from ruins, geographically or psychically.

That has not tempered the desire of artists to engage with the theme, but it has changed their approach. Jane and Louise Wilson’s photographs of concrete bunkers from the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall are anti-Romantic, but conceptually fascinating: brutalist relics from the most brutal of political regimes.

During Britain’s punk movement, artists celebrated, if that is the right word, the ruin as a banal fact of everyday life rather than as a fall from a more elegant age. In the Tate exhibition, Jon Savage’s photographs of “Uninhabited London” are an indictment of contemporary life: the ruin as failed economic policy. And Rachel Whiteread’s “Demolished” series of pictures shows the demolition of Hackney housing estates, beautiful like all explosions, explosive in their condemnation of modern housing conditions.

In a time which concerns itself with forthcoming environmental catastrophe, there is no danger of archaeolatreia monopolising the attentions of critics and artists. Forget the past; today’s ruinous visions are of the future. The fallen cities of tomorrow have little romance about them. Dystopia is a charmless place. The greatest appeal of classical ruins was to know that we emerged from them unscathed, and moved on to bigger and better things. It wasn’t lust for ruins; it was lust for life.

‘Ruin Lust’, Tate Britain, London, to May 18, tate.org.uk

————————————————————————————-

Social network of the damned

Hell is other people, wrote a famous French philosopher, who proceeded to hang out in crowded cafés all day long to show off his tricksy ways with a paradox.

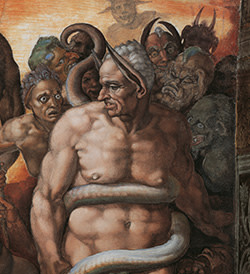

Jean-Paul Sartre was not alone in his perception, although he put it more boldly than most. Our visions of the burning place are indeed replete with bad company: crazed demons, fellow sinners, assorted exotic and frightening reptiles. In Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgment” in the Sistine Chapel, a figure with donkey ears is bitten in his private parts by a coiled snake, leaving us menfolk to ponder the subtle metaphysical question of which is the greater humiliation.

On YouTube, a South Korean woman displays her paintings of hell, having been taken there one fateful day by Jesus Christ himself. Grim viewing it makes: there are people with missing or flayed body parts, a man having rocks shovelled into his mouth, and a special corner for miscreants who have overindulged in “secular television”, in which a giant arm springs from a flatscreen set and squeezes the hapless viewers’ skulls to a pulp. (One day we will wonder why this lunacy was deemed acceptable for mass consumption, while the wholesome pursuit of mutually enjoyable sexual relations between consenting adults was considered taboo. But that’s one for the future.)

There are signs that our concept of damnation may be evolving into something quite different from an extreme version of a packed commuter train. In the Royal Opera’s visually striking new production of Don Giovanni, the opera’s climax, which normally sees the chastened – or perhaps not – seducer dragged into the flames of hell, is given a radical reinterpretation.

I have always found the ending of Mozart’s most complicated opera something of a problem, veering uncertainly between the bathos of clunky scenery and hammy acting, and something which tries to deliver a moral message, but doesn’t quite succeed. Mozart and his librettist Lorenzo da Ponte are more than a little seduced themselves by their protagonist. They can’t seriously want us to live happily ever after in the pallid world of Don Ottavio, the drippiest character in the whole of western culture.

In Kasper Holten’s production, there are no flames of hell for the reckless philanderer. Instead, as his dinner date with the undead takes a turn for the worse, he is gradually stripped of his entire world. The elaborate scenery turns plain, all technical effects are switched off. The stage is reduced to a simple backdrop, the house lights come on. He turns to the audience, and holds out his arm. His world is dead, because worldliness is all he has. Without others, he is nothing. Hell is no people at all.

…

The thought reoccurred just a few hours later when I watched the climax of The Bridge, the television series that is the most desolate of the Scandinavian noir genre, which is saying something. The Bridge is nominally about the investigation of crime, although its forensic gaze is applied still more intensely on the loneliness of the soul. We will its two protagonists, Saga Noren and Martin Rohde, to form a bond that will strengthen them, in the best tradition of cheap police drama. To share a wisecrack is to battle all that is malign in human nature.

There are moments of unusual chemistry between them. But they are both fundamentally alone, their lives stripped of most human comforts. Between them they have some serious baggage to contend with – a dead child, autism, failed marriages, Stygian evenings – and they ultimately fail. In The Bridge, the criminals might get caught, but the catchers are not afforded the luxury of satisfaction with a job well done. The betrayal of Martin by Saga in the final episode of the second series, a man haunted by what is inside his head undone by a woman cast adrift from empathetic response, is quietly shattering. Hell, here, is the inability to connect.

Sartre got it, of course. He explained his famous dictum, from his play No Exit, in a 1947 article: “We judge ourselves with the means other people have and have given us for judging ourselves. If my relations are bad, I am situating myself in a total dependence on someone else. And then I am indeed in hell.”

It bears thinking about, in the age of hyper-connectivity. We increasingly define ourselves by our relationship with the external world, which is fast and furious in its eagerness to condemn. But even worse than condemnation is neglect. Hell for me, professionally speaking, is for no one to read this column. Hell for anyone wishing to troll me is to be ignored completely.

It is solitude that is the infernal quality of today, not the plethora of fellow sufferers who crowd our hearts and minds. We are a mislaid text message away from damnation. Imagine life without the social network: it brings you out in a sweat.

Letter in response to this column:

Unfair to call Saga’s action a betrayal / From Mr Kevan Pegley

————————————————————————————-

When life was lived in three dimensions

There is something about the opening scene of American Hustle , winner of three Golden Globes last week and nominated for 10 Oscars, that makes it clear why the culture of the 1970s is making something of a comeback. In a few moments steeped in richly comedic pathos, we are taken back to a time that was both more innocent, and more sleazy. The middle-aged Irving Rosenfeld, played by Christian Bale in hefty-method mode, is attempting to make himself presentable – attractive, even – by means of a hairpiece on his head.

He manoeuvres an unconvincing tuft of dark fur on to the barren dome at the top of his head, with the aid of some glue. He arranges, with no little delicacy, various strands of his own, thinning hair above and around the tuft. With some last-minute twists and tugs before the mirror, he affords himself a tentative expression of quiet satisfaction. He is ready to face the world.

Rosenfeld’s hairpiece has already become the talk of the movie world. Expect it to walk away with an Oscar all of its own. One of the joys of the film is to follow its crazily reimagined manifestations over the course of the action. You can’t take your eyes off it, as they used to say of Garbo. We are laughing at it, of course. But there is something almost tender about it too, this preposterously transparent measure of inept disguise.

It is all very 1970s. The unpolished decade, the era of make-it-up-as-you-go-along, getting by as best you can. An age that revered posers, but didn’t mind if the poses frayed a little around the edges. When the ultimate feat of technological trickiness was a tape that could self-destruct, or a television that could be powered by remote control!

I think we miss all that. We miss the bathos of bad dancing, bad trouser-width, bad bugging of the US president’s political opponents. Ironically, we were witnessing the best that popular culture could offer: The Godfather, Blood on the Tracks, investigative newshounds, rumbles in the jungle. But we weren’t really up to it. We floundered in a haze of dissatisfaction, hung over from the previous decade’s parties, not yet ready for the onslaught of slickness and coffer-filling that was to come.

I thought of all this when I came across a report by the forecaster JWT Intelligence, which focused on cultural trends for 2014. In the main, it says, we find ourselves in something of an existential dilemma (my words, not theirs), both welcoming and resisting the growing omnipresence of technology in our lives. We are in an age of impatience. The on-demand economy, and the ability of e-business to respond to it, is making us more, rather than less, intolerant of delay. Same-day delivery is the mantra of quick-fire online shopping. Most products can be delivered in a day; but we are also expecting hyper-speedy resolution of more complex matters, like fulfilling relationships, or cures for diseases. The result is frustration.

….

Yet we also “rage against the machine”, wanting to restore human values to our increasing dependence on technology. Rock bands – always the place to look for an enlightened way forward – are beginning to insist that people put their phones away during concerts so that they can live their experience in proper 3D rather than mediate it through a three-inch screen.

We rail against tradition; we revere tradition. We want to break apart the old world while we rest against the eternal verities that have made us who we are. Gay marriage is the perfect example of this mash-up, revivifying an old institution with progressive social attitudes.

We are proud to be imperfect. Last October, says the JWT report, an Austrian grocery chain, Billa, launched its own label of “nonconformist” produce called Wunderlinge, a neologism which roughly brings together the words for “anomaly” and “miracle”. We have had enough of things looking immaculate, or rather the pressure for things to look immaculate. We are embracing flaws, things that don’t look quite right.

All of which brought me back to Irving Rosenfeld, his small-time American hustle, and his big-time delusion that he could ever have a good hair day. This was a time that hated undue haste, was a little contemptuous of the super-efficient, suspected anything pristine, and wallowed in its faults and limitations (just ask the International Monetary Fund). A time when we didn’t need reminding that life was to be lived in three dimensions.

That is why we love Rosenfeld and his hairpiece, and that funny yet febrile scene in the disco, those out-there outfits, the shady local politician who is both on-the-make and a go-to guy. Nothing was quite straightforward in the 1970s, and part of our full-haired, teeth-whitened, upright and uptight time could do with a little more of that.

peter.aspden@ft.com, @peteraspden

To listen to culture columns, visit ft.com/culturecast

Comments