Michael Ignatieff on the lessons for liberals in Nick Clegg’s memoir

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

WB Yeats’s famous lines in “The Second Coming” — “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity” — ring painfully true for liberals these days. Moderate rationalists are everywhere on the defensive, and it is the passionate intensity of Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and the motley crew who persuaded the UK to vote for Brexit making all the running.

Many are baffled by this turn of events. Nick Clegg’s memoir of his time in power is a case in point. The former deputy prime minister is appalled by the recent British referendum on membership of the European Union, repelled by the virulence of social media and amazed that a reasoned, pro-market, internationalist politics is being squeezed to vanishing point by angry nativists on the right and anti-capitalist fundamentalists on the left.

There are, he writes, with plaintive indignation, “millions of British citizens who are searching for moderation against the extremes, who want evidence and not prejudice to govern decisions, who understand that in a complex world the politics of give-and-take has its place”. But there weren’t enough such sane moderate rationalists to save him from crushing defeat. Clegg’s Politics is his attempt to explain why.

It is not an autobiography — there is little or nothing on hearth and home, early influences, parents, schooling, years of apprenticeship. It is about his five testing years in coalition with the Conservatives, an honest, likeable, rueful account of what it was like to exercise real power in a loveless political marriage and then be unable to stop the marriage from coming apart.

I’ve been in politics myself — in Canada — and know what it is like to be ground between the millstones of passionate intensity on the left and the right. I’m not sure Clegg fully understands what happened to him, any more than I do, but he does write well about defeat: from the moment his wife Miriam González Durántez raises her hand to her mouth in anguished disbelief at the first exit polls on election night in May 2015 to the funereal experience of showing up at the Cenotaph the next day with other party leaders, the Liberal Democrats stripped of 49 seats and his political career in ruins.

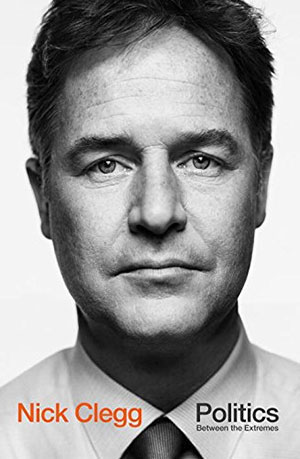

The cliché about defeat — what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger — is true but it rather glosses over the sheer awfulness of it all. Clegg has used his defeat well. He is quick to admit to two mistakes: reversing himself on university tuition and forcing a doomed referendum, too early, on electoral reform. He is even funny about the characteristic self-righteousness of liberals — the unshakeable belief in our own good faith — and comes across as a humbler and wiser character. He has chosen to put a stark photograph of himself on the cover of the book and he stares back at the reader, his eyes radiating the message: if I only knew then what I know now.

Clegg writes with charm and humour about political life but he doesn’t seem to have liked it much, the grind of constituency work, the daily knife fights with opponents, feeding and fending off the media beast. Westminster’s arcane rituals and bonhomie left him cold. What he clearly loved — and this is not always the case with liberals — was power. Every major decision between 2010 and 2015, he claims, was made, ultimately, by him and David Cameron.

It’s a disappointment that Clegg does not draw back the curtain on these mano a mano battles in Downing Street. Cameron remains all but invisible in these pages, although Clegg’s account does offer some insights into how the former prime minister’s fatal miscalculation about Brexit came about. In Clegg’s telling, Cameron never once had a strategic discussion with the rest of his cabinet about Britain’s relationship with Europe. He seems to have had no fundamental convictions on the question. His perspective was narrowly tactical — to avoid a party split — and as a tactic, the referendum turned out to be a disaster.

Clegg’s memoir is at its most vivid when he describes policy battles with lesser figures, the canny George Osborne and the duplicitous Michael Gove. The coalition relationship, which began with the sunny good faith of those pictures from the Downing Street Rose Garden, soon settled into a grinding set of transactional bargains. Clegg takes pride in winning some of these negotiations and stoutly defends his years in coalition, arguing that it was the Lib Dems who made gay marriage happen, secured free meals for all infant school pupils and fought to take millions of low-paid workers out of income tax.

Instead of getting credit for these achievements, however, the Lib Dems’ entry into coalition blurred their political identity. Clegg concedes that they yoked their own electoral fortunes to Conservative austerity policies. When these worked, the Conservatives took the credit, and when they didn’t, blame was foisted on the Lib Dems. It is ever thus in the dynamics of coalition government between unequal partners. For Clegg himself, the blame came so thick and fast during the U-turn on tuition fees that his close protection squad had to push him down in the back seat of his car so he wouldn’t be seen by demonstrators chanting “Clegg Clegg, shame on you, shame on you for turning blue”.

At election time, the Lib Dems, freed from the carapace of coalition loyalties, tried to differentiate themselves from their partners. But by then, all they could offer the voters was the promise that, if re-elected, they would prevent the Conservatives from being quite so beastly. This was hardly a winning strategy and, as Clegg manfully admits, it was all that was left of Liberal appeal in 2015.

Clegg’s experience confirms why liberal politics is losing ground to populism on the right and the left. In a political field divided into florid hues of red and blue, liberalism comes across — to use Clegg’s own words — as “insipid” and “pastel-coloured”, “a split-the-difference” politics lacking clear definition.

A more serious problem is the tendency of liberals to regard ourselves as apostles of sweet reason, the clear quiet voice in a bar room of brawlers. Clegg has a bad case of this high-minded liberal self-regard and it leaves him perpetually baffled that the people he calls populists stole support from under his nose. Presenting yourself as the voice of reason isn’t smart politics. It’s elitist condescension. Brexiters had their reasons and their reasons won the argument.

Having lost the argument, Clegg, now out of power, allows his own sweet reason and moderation to curdle into a sour rant. He writes: “I regard the referendum outcome as one of the greatest acts of national self-immolation in modern times, which over the long term will probably lead to the break-up of the UK, the possible disintegration of the EU itself, significant economic and social damage to the fabric of our society and, to all intents and purposes, the end of Britain’s role as a major world power.”

This just seems over the top. Rationally speaking, we have no real idea how Brexit is going to turn out and it doesn’t serve the European and internationalist cause to so confidently predict we are headed straight to hell. Indeed, it was dire predictions of the worst that backfired so spectacularly on the Remain campaign.

Clegg is on much stronger ground when he patiently points out that it may prove impossible to square the Brexit circle of curtailing free movement of labour to the UK while retaining free access for UK goods and services to the single market. This is what rationalism in politics is for: to insist, stubbornly, over and over, that you can’t have your cake and eat it.

Clegg’s brand of liberal moderation (and mine too) is the natural mating call of elite cosmopolitans. The problem is that there just aren’t enough cosmopolitans to win elections. Globalisation, open markets and European integration do not churn out enough winners to build stable electoral coalitions. Globalisation empowers elites economically but disempowers them politically. Clegg is a charter member of the cosmopolitan elite — Oxbridge educated, a former Eurocrat, with a multilingual marriage to a talented Spanish-born lawyer, a house in Putney and a seat in the Commons. We can quite believe him when he says his days in power made him realise that nothing is harder in politics than taking power away from the powerful, but there is little in the liberal agenda that empowers anybody but the cosmopolitan elites.

The liberal agenda of constitutional reform, devolution, rights empowerment, a transparent state, and a political style committed to rational policy argument does not hold much attraction for those left behind in globalisation’s wake. Clegg sees this but is struggling, as most of us are, to construct a liberal appeal that reaches out to frightened people, battered by an insecurity at once economic and existential. He offers policies — infrastructure investment, house construction, reform of the banks — when what the electorate wants is a narrative that persuades them that their elites actually know what they are doing. For it is not the anger of globalisation’s losers that ought to worry us most, but the blindness of its winners.

Politics: Between the Extremes, by Nick Clegg, Bodley Head, RRP£20, 288 pages

Michael Ignatieff is president of the Central European University in Budapest and author of ‘Fire and Ashes: Success and Failure in Politics’ (Harvard)

Photograph: Dave Thompson/Getty Images

Comments