Light at the end of the tunnels

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

From Paddington Station in the west to Canary Wharf in the east, more than 40 construction sites have sprung up across London and southeast England to build the capital’s first new underground line in more than 30 years. Such is the scale of the Crossrail project that it promises an increase of 10 per cent in the city’s rail capacity from 2018.

London Underground already carries more than 1.1bn passengers a year and the £14.8bn scheme – the first underground route capable of taking full-sized trains across the capital from east to west – is desperately needed, with most lines heavily congested during peak hours.

Unlike the other two full-size cross-London rail routes – the north-south Thameslink and the West London line – Crossrail has been designed to complement the 12 lines of the underground network, the world’s oldest metro system, which celebrates its 150th anniversary this year.

As most of the network dates from the turn of the 20th century, the lines run through smaller tunnels than more modern metros. Indeed, as the capital of the country that brought railways to the world, modern-day London has suffered in many ways from being a 19th century transport pioneer.

In addition to the limits of early engineering, the city’s public transport infrastructure was starved of investment for more than 40 years from the end of the second world war, when roads became the focus of government spending. It has taken billions of pounds of investment over the past two decades to get most of the network to a level of reliability to rival that of city transport systems around the world.

More than £6.5bn has been spent on upgrading three of the capital’s deep Tube lines – the Jubilee, Northern and Victoria. Transport for London (TfL) has also recently completed a huge revamp of the London Overground, which now forms a circular railway around the capital. The focus has shifted to the so-called subsurface lines – the Circle, District and Hammersmith and City – with upgrades of the other deep lines – the Bakerloo, Central and Piccadilly – still to come.

“For investment, our annual budget is about £1.2bn a year, which is huge,” says Mike Brown, managing director of London Underground. He admits the role played by public transport in a successful Olympic Games is expected to help TfL in future bids for government funds.

The impact of Crossrail on the capital’s transport infrastructure cannot be overstated. Each 200m-long train will be able to carry 1,500 passengers, which is almost twice the capacity of a Tube train.

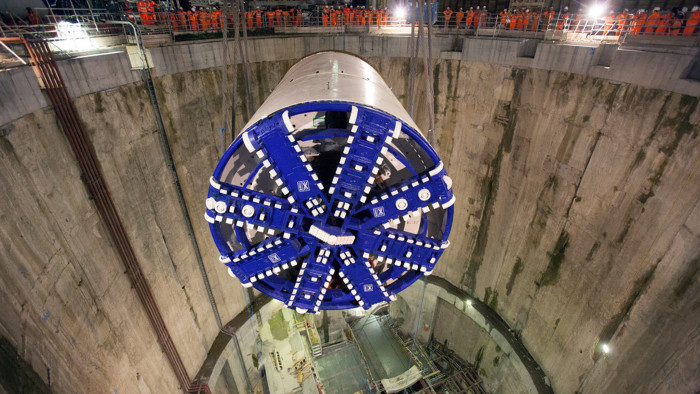

As it moves into its peak construction phase, eight giant boring machines will be at work, drilling 42km of new tunnels beneath the heart of the city. Nine new stations will be built, including four in some of the city’s busiest areas – Paddington, Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road and Liverpool Street – to accommodate the 78,000 passengers an hour who are expected to use the service during peak times. Trains will connect Heathrow airport, to the west of the city, with Shenfield, a commuter town east of London, and Abbey Wood, south of the Thames.

…

But Crossrail is just the beginning, says Mr Brown, who insists the government must find the funding to repeat this type of transformative plan if its pet transport project – a £34.5bn high-speed rail line connecting London to the north of England – is to be built.

Mr Brown says that without extra rail capacity in the capital, the terminus for the High Speed 2 (HS2) line at London’s Euston station would “fall apart” because of the volume of passengers. TfL forecasts passenger arrivals at Euston in the three-hour morning peak would jump from 23,500 in 2009 to 57,000 in 2033, when HS2 is due to be fully open.

Last month, TfL announced it was to start planning a new multi-billion-pound north-south link for London, dubbed Crossrail 2, which Mr Brown says is “imperative” if HS2 is to happen. The projected growth in London’s population of 1.5m over the next two decades is another reason Crossrail 2 is crucial, says Mr Brown.

The capacity of London’s underground and rail network is already set to grow by more than 30 per cent and he believes the same level of investment will be needed for Crossrail 2.

The cheaper option, costing about £9.5bn, would see the building of an underground line connecting Wimbledon in southwest London to Alexandra Palace in the north, via central London.

A more expensive option, which would cost at least £12bn and follow the same route, would replicate aspects of the existing Crossrail project. It would, for example, involve digging bigger tunnels under the capital to allow full-sized commuter trains to run from the mainline network into central London, connecting to services from stations including Shepperton and Epsom to the southwest, and Cheshunt and the Lee Valley region in the northeast of the capital. It could also extend to Stansted airport.

——————————————-

A bumpy start for high-speed link to the north

The tens of billions of pounds that are likely to be spent improving London’s transport links look set to be dwarfed by government plans to build the first domestic high-speed rail line to connect the capital to the big cities of the north of England.

Planning is well under way for High Speed 2, or HS2, which would allow trains to travel at 225mph. (HS1 links London to the Channel tunnel.) The cost is estimated at £34.5bn without trains, which are expected to add at least another £8bn. The link, which would connect London’s Euston station to Birmingham before splitting into lines to Manchester and Leeds, is not due to open fully until 2033 at the earliest.

HS2 enjoys broad cross-party political support and is backed by big business and the northern cities. Supporters say the country’s busiest north-south rail line – the West Coast mainline – will be full to capacity by the middle of the next decade, making a new railway inevitable.

HS2’s proponents argue that time savings and frequency of services will not only help bring the north of England closer to the capital but also benefit the whole country. London to Manchester will take 68 minutes, a saving of an hour.

The core high-speed network will run trains that are larger than current intercity carriages and could include double-deckers. Smaller high-speed trains capable of running off HS2 on to existing lines will ensure destinations not directly on the network will benefit. Journeys between Birmingham and Newcastle will fall from three hours, 14 minutes to two hours, seven minutes.

But the huge cost at a time of national austerity, and the environmental impact – HS2 will cut through some beautiful countryside – has led to fierce opposition. A strong lobby has formed to challenge the government in the courts. If successful, opponents could at least delay the project by years.

Comments