Thelma Schoonmaker: the queen of the cutting room

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Every morning, Thelma Schoonmaker heads to the Directors Guild of America building in New York, just south of Central Park, and gets to work in the editing room she first calls “my editing room” and then, immediately afterwards, “the Scorsese editing room”. It’s a trivial distinction. The last 17 films that credit Martin Scorsese as director credit Schoonmaker as editor. They include Goodfellas, Casino and, most recently, The Wolf of Wall Street , as well as the three films for which Schoonmaker has won Oscars: Raging Bull, The Aviator and The Departed.

“I only work for Marty,” Schoonmaker explains, on the phone from New York, although that’s like saying that Joe Biden only works for Barack Obama. As soon as Scorsese starts shooting, Schoonmaker starts editing. They watch the dailies together every night and he identifies the takes he likes. Schoonmaker prepares a rough cut and shows it to Scorsese, which is when the real work begins. During this “very intense” period, which often lasts as long as nine months, Scorsese is a near-constant presence in the Schoonmaker-Scorsese editing room.“He’s a great editor,” she says. “He taught me everything I know, actually. I knew nothing about editing when I met him.”

That wouldn’t be very surprising, given that they met in 1963, when Schoonmaker was in her early twenties – but it isn’t quite true. She knew just enough that a professor at New York University, where she was doing a summer course, thought she would be of value to Scorsese. Schoonmaker already had experience as an editor, having worked cutting films to fit television schedules, and Scorsese needed help finishing a short film. Later on, she cut his first feature Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1967). They didn’t work together during the 1970s, the years of Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, because Schoonmaker, who received an Oscar nomination for the documentary Woodstock, wasn’t willing to fulfil the entry criteria imposed by the editors’ union (five years as an apprentice, three as an assistant). But at some point, strings were pulled – by whom she doesn’t know – and since Raging Bull, their collaboration has been uninterrupted.

When discussing this remarkable run of work, Schoonmaker is less insistent on her contribution as editor than Scorsese’s involvement in the editing process. I suggest that she might be overlooking all that he owes to her.“Oh, I know that he cares very much about that, and he does talk about that.”

He might, I say, but you don’t. She laughs. “You would have to be here to see what an incredible collaboration it is. People think I’m always being too modest but I’m not. I know what I bring – you needn’t worry about that.”

But Schoonmaker seems reluctant to specify what it is that she brings. “He claims I pull the humanity out of his movies in the way I edit,” she says, before adding, “but he puts it in there.”

When I refer to the series of dissolves on to Sharon Stone in Casino – swift cuts reminiscent of a deck of cards being shuffled and intended to show Joe Pesci’s amazement at her beauty and glamour – Schoonmaker says, “Marty had thought that out pretty carefully. He had very strong ideas about how to create that moment and that’s why it looks as good as it does.”

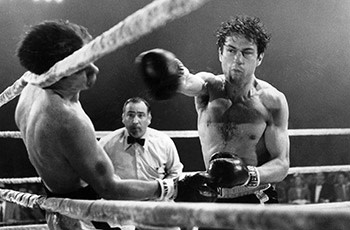

I’d hoped the moment with Pesci and Stone would testify to Schoonmaker’s significance but she identifies it instead as “a very good example of a director thinking out the shots he’s going to need in the editing”. As for the incredible movement of the films – the frenzy in the final half-hour of Goodfellas, for example, during which Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) tries to cut a large amount of cocaine for a deal, sell gun parts, take his disabled brother to hospital and make a meal; or the way we seem to zip around the Tangiers in Casino – “He gives me that movement and he’s often even thought about how it’s going to connect up. In certain fight scenes in Raging Bull, for example, the shorter ones, I literally just took the head and tail of the shot and put it together and it all worked beautifully. That’s how carefully he thinks things out.”

Scorsese’s attention to detail may have been unwavering but one thing has changed about Schoonmaker’s work over the course of their collaboration. Where she would once have worked with celluloid on an editing flatbed, through which the reels of film would be run, since Casino she has used a digital programme, Lightworks, which allows her to edit on a computer. (When Scorsese shoots on film, as was the case with The Wolf of Wall Street, the footage is transferred to a digital format.)

Has it changed things? “It’s just different,” she says. “Digital is only a tool.” But it is a tool that makes things easier. “I experiment more because I can make a copy of my edit in one second and make four or five others to show Scorsese if I feel the scene needs it – whereas on film, I had to wait until he was here, he would look at a cut, then we would try something else, I had to take the edit apart, remember how I did it.” So it makes things quicker, too? “I can access footage much quicker, yes. But in terms of living with a film and knowing what’s right, digital doesn’t do that for you.”

…

The main challenge confronted by Schoonmaker when she is handling Scorsese’s footage isn’t putting things together but paring them down. I ask her about the pre-credit sequence of The Departed, the Boston-set gangster thriller starring Jack Nicholson, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Matt Damon, and the only film for which both she and Scorsese have won Oscars. It’s a 17-minute sequence, mixing archive footage, flashbacks and leisurely dialogue scenes, which, Schoonmaker explains, was “created by necessity”.

“The introductory material was too long,” she says, “so we began just smashing things together and trying to find a very vivid way of getting the best of what we had, mushing it all into a montage. It took a long time, reducing and reducing and reducing the amount of footage and moving it around, and not worrying too much about continuity.” Or not worrying at all – viewers of Scorsese’s films don’t have to be exactly eagle-eyed to spot the cigarettes that disappear from characters’ mouths, the coffee cups that jump around.

I compare Scorsese’s willingness to make “bad cuts” for the sake of what she calls the scene’s “content” to the preference for effect over consistency shown by Schoonmaker’s late husband and Scorsese’s hero, the English director Michael Powell, in the ballet drama The Red Shoes (1948). It has often been argued that the dancer, Vicky, (Moira Shearer) shouldn’t be wearing the red ballet slippers in her death scene. She dies just before going on stage, yet in the ballet, the character doesn’t put them on them until halfway through. Why would she be wearing them?

“Oh yes!” Schoonmaker says. “Everybody told my husband he couldn’t do that. He said: ‘The red shoes are going to carry her to her death. I don’t care what you say.’ Marty and I would strongly have supported him. If you’re not going with the emotional power of the movie, then something’s wrong. It’s a subject that drives me mad.”

The Red Shoes, one of many films Powell made with his fellow writer-director-producer, the Hungarian Emeric Pressburger, has played a big role throughout Schoonmaker and Scorsese’s lives. She says it is part of their “DNA” and it is one of the films they have laboured to preserve. Scorsese has loved Powell and Pressburger’s films since he was a boy, and it was he who introduced Schoonmaker to Powell. But Scorsese had to wait for the technology to realise his ambition of restoring The Red Shoes. The problem with Technicolor prints is that the three strips of film that make up the image shrink over time and at different rates.“With digital,” Schoonmaker explains, “it became possible to compensate for the shrinkage.”

But even now, she says, it is a slog. First technicians work to remove all “the scratches and dirt and stains and fluctuations” in the print; then Schoonmaker and Scorsese spend a long time making sure that “everything is right”. So far, of Powell and Pressburger’s 19 films, they have completed only The Red Shoes and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp but they are “devoted to getting them all restored this way”. Scorsese is responsible for raising the money, which he does through his Film Foundation. “He’s just been amazing about it,” she says.

The restoration project is part of an older effort on the director’s part to correct a critical injustice. Powell is now seen as one of the greatest English directors but it wasn’t always so. When Scorsese introduced Schoonmaker and Powell at the start of the 1980s – they married in 1984 – Powell’s reputation was only just emerging from a 20-year slump. The work he did with Pressburger had been mocked by a generation of English critics; Peeping Tom, a violent serial-killer film he made without Pressburger in 1960, had caused him to be vilified in the British press and he barely worked again. Schoonmaker partly credits Powell’s revival to Scorsese, who tracked down Powell and Pressburger when they were “living in oblivion” and did all he could to publicise their work. “It was a very beautiful thing for me to watch Michael being brought back to the world,” she says (Powell died in 1990).

The latest sign of Powell and Pressburger’s return is that One of Our Aircraft is Missing, a film they made in 1942, has been packaged by Universal along with other war films such as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and Inglourious Basterds (2009) in an initiative to raise money for The Royal British Legion. Powell and Pressburger made better-loved war films – A Matter of Life and Death, for example, or The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. I asked Schoonmaker how she feels about One of Our Aircraft Is Missing. “It’s not one that I think about or talk about a lot, but I was very happy to look at it again and I enjoyed it thoroughly. It’s got a certain innocence to it,” she says.

She points to the credit sequence and the introduction of the film’s airmen characters, who crash down in Holland and must evade capture by the Nazis. “It’s as if they are doing a roll-call of the men in the plane but actually they’re introducing themselves to the audience. It’s done in a very witty way, with the little looks they give to the camera.”

Powell and Pressburger committed themselves early on to making films that helped the war effort, she explains. “But they didn’t just make propaganda films. They took the germ of the idea, given to them by the Ministry of Information and made it into a beautiful film. For example, people were worried that because Britain had gone through terrible rationing, everyone would become too materialistic – out of the kernel of that idea came I Know Where I’m Going!, which is an unbelievable masterpiece. This was the case with all the films they made in the war.”

Between continuing her own collaboration and helping to commemorate an old one, there is plenty to be getting on with. When Scorsese isn’t making a film, Schoonmaker spends her time dealing with Powell’s correspondence – “and there is usually a documentary we’re doing, on the history of cinema”. And when Scorsese is making a film, she works seven days a week. “And very long days,” she says. A lot of coffee then, I ask? She laughs: “Yes – but I’ve been doing it for years and I’m still here.”

‘One of Our Aircraft Is Missing’ is part of a new range of DVDs about military conflicts past and present, released by Universal Pictures (UK) from May 12. Fifty pence from each DVD sold will be donated to The Royal British Legion

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments