Business pioneers in technology

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

You do not have to be a young and inexperienced outsider in business to change the world in the computing and internet industries. But it certainly helps.

More than half of the industry’s leading pioneers founded their companies before their 27th birthdays, from Sony’s Akio Morita in 1946 (aged 25) to Mark Zuckerberg, who set up Facebook in 2004 when he was only 19, though that was still three months older than Bill Gates when he started in software.

It is not just the relative immaturity of the computer and internet worlds that accounts for this bias towards youth. It also reflects the industry’s periodic upheavals, as successive waves of new technology have risen to overwhelm what came before. At such times, it is often the outsider with the different perspective who emerges on top.

Youth has been a more pronounced factor in the software and internet industries than in electronics and hardware. Thomas Watson was 40 when he joined the business machinery company that he later renamed IBM, building it into the first behemoth of the computing era, though he retired just as the first commercial mainframes hit the market. Ren Zhengfei, a former Chinese army officer, was 43 when he started Huawei, the communications equipment company.

Yet both men created business empires that conform to another truism of the tech world: founder-led companies have tended to dominate the industry.

Only Lou Gerstner, a career manager, was not involved in the early days of the company where he made his greatest impact. But by reviving a struggling IBM in the 1990s, he pulled off a turnround that was unrivalled in the history of the tech industry — at least, until Steve Jobs returned to a foundering Apple and rebuilt it to become the world’s most valuable company.

While making hardware was the main route to riches in the industry’s early days, the biggest fortunes in tech have been made by more intangible means: creating the software code or the online services on which the digital world increasingly depends.

Grabbing a central role in each new generation of technology — from mainframes to personal computers and now mobile and cloud computing — has been a big determinant of success. By turning their technology into a platform on which others in the industry depend, the most successful tech entrepreneurs have been able to create a self-reinforcing cycle that has often made tech a winner-takes-all business. Microsoft’s PC software remains the most effective platform monopoly, making Gates still the world’s richest man, according to the Forbes billionaire list, even though the company he founded has been superseded in the mobile computing era.

Steve Jobs, as in so many things, stood apart. His focus on selling hardware — even as software such as the iOS operating system and services such as the App Store accounted for much of his success — has made Apple the odd man out.

In Strategy Rules, a forthcoming book about the pioneers of the PC era, US business school professors David Yoffie and Michael Cusumano point out that Jobs remained only a halfhearted fan of the platform strategy on which so many tech fortunes have been built. It is still unclear whether this has led to Apple yielding long-term dominance in the mobile industry to Google’s Android operating system, they say.

Like the tech industry itself, the list of pioneers reflects the historical dominance of the US. But as tech producers in the developing world move up from electronics manufacturing and routine outsourcing to higher-value services — and as participation in digital markets booms thanks to the spread of mobile technology — it is a fair bet that many in the next generation of industry leaders will come from elsewhere.

Jack Ma of ecommerce platform Alibaba may not have made this listing of industry pioneers, but along with Pony Ma of internet company Tencent and Xiaomi’s Lei Jun — the handset entrepreneur whose rock-star status in China echoes the passion once aroused by Jobs — he is one of a generation of Chinese tech entrepreneurs who could be on the brink of global prominence.

With each successive computing platform assuming greater significance than the one that came before — and subsuming a bigger slice of economic activity — it is also likely that the fortunes of the future will also put those that came before in the shade.

But there is also a dark side to this inexorable turn of the tech industry cycle. If founder-run companies have dominated, can they withstand the departure of the pioneers who gave them life? And as the opportunities from each new generation of technology grow bigger, will the half-lives of the leading companies grow shorter?

IBM, which has been in business for more than 100 years, represents a longevity that seems to be passing. Tellingly, it is already in need of another turnround, only two decades after Gerstner hauled it back from the brink.

Microsoft missed the rise of mobile computing, while Google has missed the social media wave and has yet to show that its core search service can be as dominant in the mobile world as it was on PCs.

Even Zuckerberg has had to address the risk of being eclipsed: at the age of only 30, he was forced to spend $22bn to buy messaging service WhatsApp last year to prevent Facebook fading into irrelevance in the mobile age.

Amid the upheaval, the foundations of the industry’s next dominant businesses are already being laid.

Sergey Brin & Larry Page

As graduate students at Stanford University, Larry Page and Sergey Brin did not set much store by the idea of building an advertising business, writes Richard Waters. In the academic paper laying out their ideas for a new type of search engine, they explained that to take paid messages would risk compromising the integrity of their service, adding: “We expect that advertising-funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.”

The qualms did not last: instead, they ended up creating a system of search-related advertising that has served as one of the main economic drivers of the consumer internet industry in its first two decades.

Page and Brin are best known for innovations in web search — not to mention their long-range ambitions, such as driverless cars. But it has been in advertising that they have had their biggest impact on the business world. The idea of search advertising was pioneered by Overture, another internet start-up, but perfected at Google.

Online display, mobile and video advertising have followed: with revenues of $66bn, around half of the world’s digital advertising flowed through Google’s systems in 2014. The data amassed from the company’s growing range of services have served to feed this unparalleled advertising machine — though that has also raised privacy worries.

The Google co-founders have taken different directions of late. Brin has taken an interest in longer-range projects, notably through Google X, the company’s ambitious research labs — though Glass, the augmented reality headset and one of the first products of X, has failed to catch on.

Meanwhile, as chief executive, Page has sought to remake Google for a future that stretches far beyond search. His vision of using Google’s massive profits to turn it into a holding company with interests ranging from devices for the “smart home” to treatments for the diseases of ageing could lay the foundations for a new type of digital conglomerate.

Still in their early 40s, the founders now face two questions that will determine how their careers are eventually reflected in the business history books. Can they succeed in giving Google a new lease of life as social networks and mobile app stores come to dominate digital life? And will they be able to deal with the wave of resentment, jealousy and fear that has been stirred up by their success, particularly in Europe?

For the next phase of Google’s history, diplomatic and political skills will be as important as the engineering and business acumen Brin and Page have shown in the past.

Bill Gates

If turning points in business history can be traced to single events, then a meeting that took place in Boca Raton, Florida, in the autumn of 1980 will go down as a seminal moment, writes Richard Waters.

At 24, Bill Gates, who had dropped out of Harvard University to go into business with school friend Paul Allen, had already created one of the first software companies built for the new microprocessors that would define the personal computer era.

But it was the deal he struck in at the 1980 Florida meeting with executives from IBM that sealed the fate of much of the tech industry for the next quarter of a century — while turning Gates into one of the world’s richest individuals.

The IBM meeting showed Gates at his most effective: the master strategist and determined negotiator whose superior understanding of what was at stake enabled him to walk off with the prize. In agreeing to make the operating system for IBM’s PCs, Gates made sure he kept full control of the source code and the rights to sell the software to other manufacturers — terms that led to the commoditisation of PC hardware and Microsoft’s massively profitable operating system monopoly.

Eventually, however, Gates’s uncompromising competitiveness brought an anti-trust lawsuit from the US government. A court-ordered break-up of the company was avoided only with a settlement that saw Microsoft bow to years of close government supervision.

For much of his time as chief executive, Gates’s strong personal leadership enabled Microsoft to respond to new technology threats. His rallying cry about the risk of Microsoft being swept away by an “internet tidal wave”, for instance, galvanised its developers and enabled it to fend off the threat from browser developer Netscape.

After the fight with the US government, Gates stepped down from running the company to focus on directing its technology. Microsoft’s wealth and PC dominance remain intact, though Gates was unable to position the company to lead in the next phases of the personal computing and internet revolution, from web search and social networking to the rise of mobile internet access.

Unusually among his generation of technology entrepreneurs, Gates opted to quit the company he founded and start a second career, leaving Microsoft at 52 to focus on philanthropy. With its massive budget and ambition to improve life in emerging nations, the foundation could one day rival the founding of Microsoft in terms of its impact on the world.

Andy Grove

The title of Andy Grove’s memoir says it all: Only the Paranoid Survive, writes Sarah Mishkin. It was a lesson the co-founder of Intel learned young. He grew up in Hungary as András Gróf, a Jewish child during the Holocaust, and spent his early years with his mother racing between hideouts in Budapest and rural Hungary to outrun the invading Nazis. He fled to the US after the Hungarian uprising of 1956.

He ultimately graduated from university, moved to California and got a job in the nascent semiconductor industry. Ultimately, he partnered with Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, key developers of the silicon chip, to launch Intel.

Today, Intel is the world’s largest semiconductor company by revenue. Its chips are used by everything from Apple computers to the servers in the massive data centres that power many of the world’s most popular apps. For the average consumer in the developed world, to go through a day without relying directly or indirectly on an Intel product would be difficult.

Yet Intel’s growth was not always so assured, and Grove played a key role in leading the company to success. He helped see Intel through a crisis in the mid-1980s ultimately to emerge as the leading microprocessor company it is today. Japanese companies were driving prices down in memory chips, which then comprised an important part of Intel’s business. Most of its research and development went into memory. Microprocessors, effectively the brains of computers, were but a small business.

Amid that turmoil, Grove pulled a daring move: leave the business of memory entirely and bet the house on microprocessors. It changed the identity of Intel and required the laying off of thousands of employees and closing of plants.

The lesson Grove learned about the value of being proactive — paranoid — remain applicable, perhaps even more so now as industries are being shaken up by the accelerating pace of technology. He made a presentation to the Intel board in the mid-1990s about the importance of the internet. Not everyone was convinced it was more than a fad. But Grove pressed on with his argument that the company needed to be proactive in figuring out how the world wide web would affect the business.

“In technology, whatever can be done will be done. We can’t stop these changes. We can’t hide from them. Instead, we must focus on getting ready for them,” he wrote. “We won’t harness the opportunity by simply letting things happen to us.”

Steve Jobs

The name on the door of an office on the fourth floor of One Infinite Loop still reads “Steve Jobs”, writes Tim Bradshaw. Four years after his death in October 2011, Apple has left its co-founder’s room in its Silicon Valley headquarters untouched.

Since that time, Apple’s share price has more than doubled thanks to ever-increasing iPhone sales, under the leadership of Jobs’s successor, Tim Cook. Jobs’s principles of focus, simplicity and striving for perfection still guide Apple today.

Jobs pioneered not one but three great businesses — only two of them named Apple. After ushering in the birth of the personal technology era, as chairman of Pixar he helped to turn the animation industry digital with Toy Story. Then he upended the music industry with the iPod before creating a far more ubiquitous kind of computing with the iPhone.

Throughout each transformation of Apple and its adjacent industries, Jobs was dynamic yet difficult. Accounts of his management style often bring up his ruthless and capricious nature. In Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs, former Apple chief executive John Sculley describes Jobs’s staring contempt as “like an X-ray boring inside your bones”.

Yet that same force of personality could be used to drive his colleagues to achieve things they never believed themselves capable of.

Jobs may have taken advantage of innovations created elsewhere, such as Xerox Parc’s mouse, but his genius was in bringing them together as a complete package, accessible to all. In an industry where many see technological advancement as ever-greater complexity, Jobs stood for the intuitive. “The reason that Apple is able to create products like the iPad is because we’ve always tried to be at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts,” Jobs said as he introduced the tablet computer in 2010.

A year later, he explained: “It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough. We think we have the right architecture not just in silicon but in the organisation to build these kinds of products.”

Perhaps Jobs’s greatest achievement was not any single product but his ability to form an organisation that could repeat such innovations, and is not afraid to disrupt itself to move forward. “You can clearly feel him in these products and you can feel him in the company,” Cook said last year. “His DNA will forever be the foundation of the company.”

Akio Morita

Akio Morita, the co-founder of Sony, changed the face of Japan’s tech industry, elevating the country’s gadgetry creations into what he called “the Cadillac of electronics”, writes Kana Inagaki. Morita, together with Sony’s innovations, from the Trinitron colour television to the Walkman cassette player, personified Japan’s rise in the wake of the second world war. The products he helped to deliver revolutionised the way people worldwide listened to music and watched TV.

Born in 1921 as the eldest son of a wealthy sake-brewing family, Morita broke with tradition by leaving his family business in his mid-20s to set up a tiny electrical engineering firm inside a bombed-out department store building in Tokyo. The start-up, founded with his partner Masaru Ibuka in 1946, rapidly expanded to become one of the world’s most iconic consumer electronics brands.

If Ibuka was the engineering genius, Morita was the energetic and charismatic salesman who travelled around the world. His business acumen was reflected in his shrewd branding strategy, which kept prices competitive during a period when Japanese goods were seen as poor-quality replicas of western products.

Sharing the same scepticism towards market research as Steve Jobs of Apple, Morita said the Walkman would not have been born from asking consumers what they wanted. In fact, very few, even inside Sony, except Morita, imagined the Walkman would be a hit.

Morita, with his trademark silver hair, was also an avid and at times controversial spokesman for Japanese business, criticising what he called the US industry’s preoccupation with short-term profit.

Defying convention catapulted Sony’s products to international recognition, starting with the pocket-sized transistor radio in 1955, followed by the portable transistor TV in 1960 and the Trinitron colour TV in 1968. With the Walkman in 1979, Sony heralded the age of mass-market, portable music.

Narayana Murthy

Narayana Murthy’s reputation as a pioneer of Indian software seemed secure when he stepped down as chairman of Infosys, writes James Crabtree. He had co-founded the business in 1981 and led as chief executive until 2011, in the process becoming perhaps the most recognisable figure in the country’s fast-growing outsourcing sector.

But his crucial importance was only underscored two years later. Infosys had lost its way since his departure, its record of rapid expansion replaced by an image of rocky financial performance, and the board unexpectedly asked him to return from retirement.

An occasionally taciturn leader with an exacting eye for detail, Murthy helped Infosys during his second stint to rediscover some of the traits that helped India’s information technology sector flourish, including a renewed focus on its traditional strength of providing basic services to leading global companies at prices far below those of foreign competitors.

The company’s performance stabilised and morale improved. When Murthy handed over to his successor just a year later, he admitted that the group’s turnround was unfinished, but most analysts agreed it was at least under way.

Beyond his role at Infosys, Murthy’s career symbolises something more profound about his country’s development. As an entrepreneur, he enjoyed an image for honesty and modest public pronouncements that belied his billionaire status.

“Many intelligent people possess a high ego and low patience to deal with people less capable than themselves,” he wrote in his valedictory letter to shareholders in 2011. “Leaders have to manage this anomaly very carefully, counsel these errant people from time to time, and allow them to operate as long as they do not become dysfunctional.”

The story of Infosys’s foundation in 1981 in Pune with just $250 in start-up capital (it soon relocated to the developing information technology hub of Bangalore) became a metaphor for the possibilities of India’s own growth. In a country where business remains dominated by family-run conglomerates and lumbering state-controlled enterprises, Murthy and his Infosys co-founders came to represent something different — entrepreneurs with ordinary backgrounds who created a world-leading new industry through a mixture of education, innovation and determination.

At the time of Murthy’s return to Infosys, Meera Sanyal, the former head of Royal Bank of Scotland in India and a one-time Infosys client, summed up why the career of this elder statesman of Indian software had taken on such outsized significance. He “represented a middle-class aspiration to win in business, but do it in a clean way”, she said. “He became like a beacon of hope, and all of us felt a sense of pride in what he accomplished.”

Ren Zhengfei

Ren Zhengfei, a former army engineer, recalls that his start in business was somewhat rocky, writes Leslie Hook. When he left the People’s Liberation Army to go into business in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen he quickly ran into problems: he knew nothing about how a market economy worked. Nor did the rest of China — the country was in the midst of a profound transition from a state-run economy to “capitalism with Chinese characteristics”.

Huawei, the company Ren founded in 1987, is now one of the biggest global symbols of capitalism with Chinese characteristics. With $47bn in sales last year, Huawei has outpaced Ericsson to become the world’s largest provider of telecommunications equipment.

It has not always been easy. Ren studied architecture at university — shortly before the disastrous years of the Cultural Revolution — before joining the army. He then tried his hand in communications because “we thought that the communications market was so big, filled with plenty of products”. Money was tight in the early years. “We survived by paying a high personal cost,” Ren, 70, said in a recent Davos talk. “There was no turning back because we had no money left. That was how we started.”

As one of China’s most prominent global brands, Huawei, with its rapid expansion around the world, has at times tested the limits of its welcome, particularly in the US. Huawei has repeatedly lost out on US contracts, partly because of concerns voiced by US lawmakers over Ren’s past military connections.

These concerns are fuelled by a legacy of secrecy: Huawei does not identify details of its shareholding structure, other than to say it is owned by 80,000 employees. Prior to 2011 it did not disclose the identity of its board members.

Huawei has enjoyed spectacular growth and expects revenues to grow 20 per cent this year to $56bn. While most of its sales come from telecoms equipment, its fastest-growing segment is in enterprise, where it provides data centre and cloud computing products.

Debate lingers over whether, and how much, Huawei has benefited from government ties. “The US government believes Huawei represents socialism,” Ren said at Davos. “Some people in China believe that Huawei is a capitalist bud, simply because many of our employees hold shares. What do you think Huawei is? I can’t give you a definite answer today.”

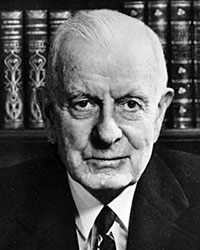

Thomas Watson Sr and Lou Gerstner

Thomas Watson Sr and Lou Gerstner both came from working-class backgrounds to head a company whose progress has done much to define the first century of the information age, from punch cards to mainframe computers and the complex information technology systems on which modern corporations depend, writes Richard Waters. But they could hardly have been more different.

A natural salesman who adopted the patrician style of the business establishment he rose to head, Watson sold pianos, shares and cash registers before ending up at the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company in 1914. He quickly became president, renaming it International Business Machines a decade later to reflect its spreading range of office equipment.

In nearly four decades at the company, Watson built a culture that became synonymous with mid-century corporate America. Big Blue became known for its dark-suited salesmen and emphasis on loyalty to the company. He also helped to establish the blueprint for the modern, multi-divisional company, with a declared focus on customers, employees and shareholders, in that order.

“The clouds of doom never gathered on Watson’s horizon,” the New York Times noted in its obituary in 1956. The optimism, it added, had helped earn him the reputation of being “the world’s greatest salesman”.

IBM’s success made Watson the first monopolist of the computing age to come up against US antitrust regulators, thanks to its dominance of the tabulating machine market. A later case revolved around mainframes, though the products with which the IBM name is almost synonymous were only just being introduced on his retirement in 1952.

By the early 1990s, however, IBM was struggling, unable to compete with the wave of low-cost technology that came with the rise of personal computers. It took a very different leader to drag it back from the brink.

Gerstner had the drive and focus on operational detail to rescue IBM. He had honed his skills at Harvard Business School and McKinsey, the consultants, before taking on senior roles at American Express, the financial services company and conglomerate RJR Nabisco.

Gerstner’s tough style of leadership was jarring for the IBM rank and file, but turned out to be the medicine the company needed. His focus on operational excellence and refusal to consider sweeping strategic changes at the company were summed up in one of his first public statements: “The last thing IBM needs right now is a vision.”

Before Steve Jobs rebuilt Apple, Gerstner’s revival of IBM stood out as the tech industry’s most celebrated turnround — though a quarter of a century on, the rise of cloud computing threatens IBM’s long-term position in corporate IT and raises new questions about its leadership.

Mark Zuckerberg

He created the world’s largest communication network, is building drones to beam down the internet to far-flung corners of the globe and has become such a figure in popular culture that he recently launched a book club to rival Oprah Winfrey’s, writes Hannah Kuchler.

Mark Zuckerberg’s journey from Harvard bedroom to Silicon Valley billionaire was made famous by the film adaptation, The Social Network. His creation, Facebook, started as a way to track classmates online and grew into a network of almost 1.4bn people. Facebook has shaped how we interact, pushing new words such as “likes” and “friend requests” into the 21st-century lexicon.

But the company’s chief executive is determined for that to be just the first chapter. He has set his sights on Facebook’s oft-repeated aims of “connecting everyone”, “understanding the world” and “building the knowledge economy”. He wants to bring every one of the world’s 7.1bn people online, make Facebook into a searchable database to rival Google using the network to help people create jobs and companies, as well as increase productivity.

Zuckerberg is an evangelical founder, comfortable with telling shareholders he believes in far more than making money. When asked why his Internet.org initiative to connect more people in developing countries to the internet mattered to investors, he hit back: “It matters to the kind of investors we want to have.”

Zuckerberg is just as driven in other areas of his life, including his philanthropy — he topped the list of US philanthropists making big donations in 2013 with his gift of Facebook shares worth almost $1bn to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, which works to support Facebook’s neighbours.

He takes on ambitious new year’s resolutions, such as learning Chinese, which he recently showed off in China to much acclaim, and reading a book every fortnight. Being a — if not the — key proponent of the social media sharing culture, Zuckerberg invited his followers to read along, showing his soft power by causing a book by a former trade minister in Venezuela to sell out.

Comments