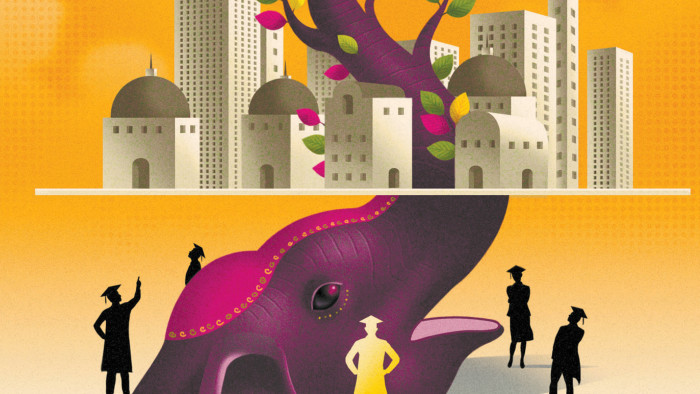

Social enterprise rises in India

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This year, the Indian School of Business did something that few management institutes on the subcontinent would have dreamt of five years ago: it published research that analysed solutions to one of India’s many social woes, its chronic lack of housing.

Until very recently, India’s management institutions had but one aim – to train managers for positions in banks and conglomerates. But that has changed, and the Centre for Emerging Markets Solutions at ISB, which published the research, is emblematic of the transformation. India’s business schools are now trying to create well-rounded leaders, who can both land a job with an Indian conglomerate or start a small business to tackle India’s vast social problems while also turning a profit.

Nikhilesh Sinha, an author of the report “New Frontiers in Affordable Housing: Notes from the Field”, says the proposal was simple: India’s housing shortage is massive, and solving it will require dedicated and sustained government action that is currently lacking. But the private sector can tackle part of it: the shanty towns and housing needs that spring up around industrial projects outside of cities.

“There are many issues that we don’t touch on, such as slums [in cities] and so on and so forth, because those are problems that will require much greater concerted effort from the public and private sectors,” says Mr Sinha. “But what we have found is that outside cities is where the private sector can provide housing for people working in industry.”

Through its research on affordable housing, the centre helped to create a 218-unit pilot project outside Rajkot, a city in the western state of Gujarat heavily involved in the car industry.

A model for educationIt is not just in India that business models are helping to address social issues, writes Della Bradshaw. In the US James Johnson, director of the Urban Investment Strategies Center at the University of North Carolina, has set up a laboratory school to solve some of the education problems faced by children from low-income families.

He hopes to replicate the best practices throughout schools in the area. “Teachers have to have high expectations for all kids,” he says.

The school, which opened its doors in 2009, now teaches 140 children between the ages of five and 10. Classes run until six in the evening, and throughout the usual school holidays. Children who arrive early are encouraged to sit down and read. “Most poor kids come to school with a reading deficit. We use every waking moment to catch these kids up. It’s all about expectations and imposing structures and routines.”

The purpose-built school includes a gymnasium, playgrounds, an urban garden and an industrial kitchen to cater for meals – including a “grab-and-go” dinner to take home.

Students also have classes more redolent of a business school, such as entrepreneurship. And 100 MBA students from the Kenan-Flagler school mentor the children – all useful business contacts for when they begin work, says Prof Johnson. Perhaps the most novel idea is that all the children are taught to speak Chinese – through rap music.

The centre helped raise private capital from commercial investors, and designed the entire system – from how the units looked to a business model that treated housing as inventory, rather than appreciating assets as Indian developers traditionally do.

That model, according to the report, yielded an internal rate of return of 100 per cent, despite the project’s relatively slim profit margins, while keeping costs to homebuyers controlled. The day the project launched, in August 2010, developers presold 148 of its 218 units.

This new-found focus on social entrepreneurship only began to take hold in India a few years ago, says Madhukar Shukla, organisational behaviour and strategic management professor at XLRI School of Business and Human Resources in the eastern city of Jamshedpur.

“Now many of the business schools are looking beyond their typical corporate goals, [and realising] there are other models that can make a profit while making a social impact,” says Prof Shukla, who teaches a social entrepreneurship class and is launching a social venture incubator at XLRI. “Given what is going on in India with the social needs and the disparities, there is a need for talent to go in that direction . . . there is a realisation that only profit motive will not help the country.”

India’s development problems are daunting: 900m people are undernourished, 800m live on less than $2 a day, and more than 600m lack access to a lavatory. There is little sense that the government is up to the task of solving the country’s myriad problems.

The good news, academics say, is that New Delhi seems to be aware of that fact. Later this year, the University Grant Commission is set to host what may be the country’s first government-sponsored conference dedicated to social entrepreneurship.

Ajit Rangnekar, dean of ISB, which has campuses in Hyderabad and Mohali, in Punjab state, says that he now finds the government much more receptive towards the part of his school’s mission that works with industry, government and society on issues that impact social good.

“The more I interact with the government, the more I realise that they recognise the value of research, they recognise the value of supporting and funding that research and they are willing to do it,” he says. “But somehow or other, between their global desire and our abilityto implement as a universe of universities, there is a gap somewhere.”

Part of the problem is the lack of any structure to unite those schools pursuing social enterprise programmes, to create a universal curriculum or a venue in which fundraising can be fostered and ideas shared.

To that end, in November last year, ISB and the Khemka Foundation, the Indian non-government organisation, hosted a forum for faculty from seven schools, including the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, the Xavier Institute of Management in Bhubaneswar and XLRI. The forum’s aim was to connect the social enterprise community within the handful of elite institutions.

As a first step, the faculty collated their syllabuses with the hopes of creating a teaching resource book.

For now, ISB’s Centre for the Study of Emerging Markets is trying to find ways in which the state can create policies to allow industry to find market-based solutions to India’s developmental problems. It focuses on socioeconomic problems – small and medium enterprise funding, healthcare finance, employability and education, and affordable housing – using India as its testing ground for ideas it hopes to export to the rest of the developing world.

It focuses on incubating businesses that can be backed up and spun out through investment from the SONG Investment Company – an equity fund created by Soros Economic Development Fund, Omidyar Network and Google in partnership with the ISB.

India’s development issues are vast, but schools such as ISB, XLRI and the prestigious IIMs are waking up to the fact that they can create leaders who are profit-focused without being blinded to India’s many blights.

“This is not charitable work; this is profitable work,” says Reuben Abraham , ISB professor and head of the emerging market centre. “[Students] see the idea of combining social relevance with the ability to do something interesting and something where there is real money to be made, [and realise] they don’t have to compromise on that part of it.

“The fact that it is not [simply] charity is extremely attractive to the students.”

Comments