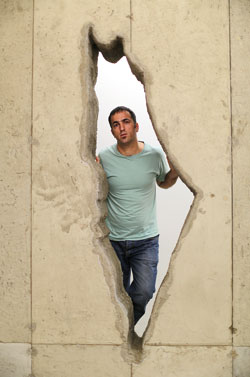

First Person: Khaled Jarrar

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When I graduated from the Palestine Polytechnic University with a qualification in interior design, I had no intention of becoming a soldier.

I wanted to carry on my studies, so I joined the police force in order to pay for it. I mostly did night shifts so I could study during the day.

During one of my shifts, officers from the Presidential Guard arrived, looking for new recruits. They offered to pay my university fees and I was persuaded. So, at the age of 21, I became part of Yassir Arafat’s Presidential Guard.

There were 18 of us guarding Arafat in Ramallah in the West Bank and another team in Gaza. We worked 40, 50, 60 days at a time; then we’d go home for four days. I had to build my muscles and make my shoulders bigger to look like a guard. I stopped studying because I was working so much, sometimes 14 hours a day. Arafat didn’t sleep. He’d keep working; he’d keep travelling. And I was never asleep when he was awake.

My role was to give my life for Arafat. He was very clever and charismatic. He got exactly what he wanted from you, and he never gave much away. Nobody, not even his wife, could say they really knew him. Still, in the years before his death in 2004, I became quite close to him.

I will never forget the day my eldest son met Arafat. He was just three or four months old and I had brought him with me to work. I was wearing my uniform, carrying my gun in one hand and my son in the other. Arafat saw him and said, “Oh, what a lovely child!” My son reached out and tried to take off Arafat’s glasses and Arafat kissed his hand.

Of course, Arafat was always under threat. The worst time I remember was when the Israeli army surrounded his compound in Ramallah on March 29 2002. They had tanks, helicopters and snipers and we only had Kalashnikovs. There was nothing we could do.

I was shot in the leg with two dum-dum bullets – the kind that explode into tiny pieces.

I was in hospital for weeks and I had crutches for six months afterwards. I still have something like 20 pieces from the bullets in my leg.

Being in hospital made me think about who I was. I was a professional soldier trained by Palestinians and various other nationalities.

But I just followed orders. I was not myself; I belonged to someone else.

So when I went back to the army it was as a photographer, not a soldier. My new role helped me reassess my past. Looking at the soldiers through the lens of my camera, I always saw myself among them in the frame.

At the time, checkpoints were a big part of my life because every time I went to visit my family I had to pass through them. I took many pictures at the checkpoints in the West Bank, and in 2007 I hung the pictures on the fences by the Hawara checkpoint at the entrance to the city of Nablus for people to see.

Now I’m a full-time artist, working across photography, video and sculpture. Some of the sculptures in my new exhibition are cast from concrete that I chiselled off the West Bank wall. One is a football: it was inspired by some kids I met in a village whose football yard was partitioned by the wall. If their ball flies over the wall, they can’t retrieve it – or they risk being shot. The piece is about changing the function of the wall from separation to something else.

I respect Arafat because he gave his life for the cause of Palestine. But I see now that he made some mistakes – like signing the Oslo Accords in 1993. Back then, I was a soldier, not an artist, and I was following orders. But I don’t like following orders. I like to be honest and say what I see.

‘Khaled Jarrar: Whole in the Wall’, Ayyam Gallery, London, until August 3; www.ayyamgallery.com

Comments